Marian Anderson and pianist Kosti Vehanen perform for a crowd of thousands at the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939. University of Pennsylvania, Marian Anderson Collection of Photographs.

Mary McLeod Bethune In late 1935, Marian Anderson returned home to the United States in triumph from a European tour. Hers is “a voice such as one hears once in a hundred years,” declared the famed Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini. The New York Times music critic wrote that the “Negro contralto” was “mistress of all she surveyed,” and compared her to perhaps the only African American more famous than Anderson at the time, the boxer Joe Louis. The rest of the New York press followed suit, particularly after a famed appearance at Carnegie Hall in January 1936. Similar reviews and accolades met Anderson’s appearances in Atlanta, Tuskegee, Alabama, and Hampton, Virginia, where she attracted primarily African American audiences in segregated venues, and in Chicago and Utica, New York, where, as at Carnegie Hall, the audience was predominantly white. No performer had ever reached that degree of crossover appeal.

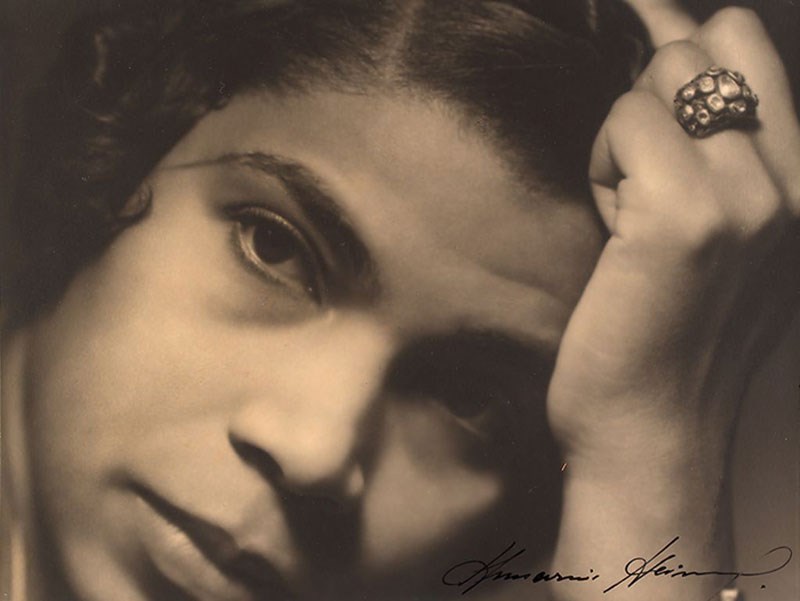

Marian Anderson by Charles de Flaugergues, ca. 1934. University of Pennsylvania, Marian Anderson Collection of Photographs. By February 1936, Anderson set her sights on Washington, D.C., where she had not performed since 1933. In light of her growing celebrity and Carnegie Hall triumph, the venue was switched from Howard University’s small Rankin Chapel to Armstrong High School Auditorium, one of the largest venues in the city that allowed African American performers on stage. The city’s largest auditorium, the four-thousand-capacity Constitution Hall, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), had barred African Americans from appearing on its stage since 1931. Anderson’s recital at Armstrong High School sold out, with around one hundred white audience members, and it was a critical success like the earlier dates on her tour, though one Black reporter noted that the “auditorium was far too small to hold the crowd that wanted so badly to get it.” The next morning, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt invited Anderson to perform in the White House at a private dinner. ER had requested a “spirituals only” program, but Anderson insisted on also including selections from Schubert, a choice the first lady endorsed in her “My Day” column. “My husband and I had a rare treat Wednesday night,” she wrote, “listening to Marian Anderson, a colored contralto, who has made great success in Europe and this country. She has sung before nearly all the crowned heads and deserves her great success, for I have rarely heard a more beautiful and moving voice or a more finished artist.” Over the next two and a half years, Anderson continued to tour to packed venues and critical acclaim at home and abroad. She performed in Spain, just before the outbreak of its civil war, France, England, Belgium, Holland, the Soviet Union, and Austria in 1936. Bruno Walter, a German Jewish conductor exiled from his homeland after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, had just come out of retirement to direct the Vienna State Opera, despite death threats and disruptions to his concerts. Determined that his show would go on, Walter invited Anderson to sing Brahms’s “Alto Rhapsody” at that year’s Vienna Music Festival, a double rebuke to ideas of white or Aryan supremacy. Germany itself remained off limits to a “non-Aryan” artist, but Scandinavia, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia were more hospitable, as were the South American nations she toured in 1938. Several concerts on her US tours in 1937 and 1938 were also broadcast to millions of listeners on NBC radio. Anderson’s appearance with her white accompanist, Kosti Vehnanen, was unprecedented among major performers, but did not provoke any controversy where they appeared before segregated audiences, even in Texas and Oklahoma. In Princeton, New Jersey, Anderson was refused a hotel room on account of her race. Fortunately, a Princeton resident, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Albert Einstein, a German Jewish refugee, heard of her plight and invited her to stay with him, initiating a deep and lasting friendship. By January 1939, Anderson’s fortunes had been transformed. Her income from concert fees alone the previous year had neared a quarter-million dollars. But soon it would be time for another appearance in the nation’s capital. Anderson’s manager knew it would be problematic because of the ongoing ban on Black artists at Constitution Hall. Concert organizers wondered if the DAR might come around and allow four thousand aficionados in the district a chance to enjoy the “voice that one hears once in a hundred years.” When he learned the DAR would not budge, Walter White of the NAACP swung into action. First, he assembled endorsements from prominent musicians and conductors including Toscanini and Leopold Stowkowski. Then he arranged that the NAACP award its highest honor, the annual Spingarn Medal, to Anderson, persuading Eleanor Roosevelt to agree to present it at a ceremony in July. But it was only once ER discussed the issue with White and announced her resignation from the DAR in “My Day” on February 27th that the color ban at Constitution Hall became a national cause célèbre. By resigning her membership of the DAR, Eleanor Roosevelt grasped an opportunity to lead—in the most enlightening way she thought possible—on the issue of equal rights for all Americans. It was a gamble. Nevertheless, she persisted, inspired perhaps by Anderson’s own success against the odds, as a working-class African American from South Philadelphia who had honed and refined an early talent for music to become the most celebrated singer of her day. In the White House and the Cabinet, Anderson’s strongest supporter other than Eleanor Roosevelt was Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior. Weeks before ER’s resignation, Ickes had made his views plain in a stinging letter of rebuke to the DAR for the “astounding discrimination against equal rights” in its exclusion of non-white performers. And Ickes, a former president of the Chicago NAACP, proved to be a very useful ally once Walter White proposed the Lincoln Memorial as an alternative for Anderson’s Easter Sunday concert. On March 30, just ten days before Easter, Ickes secured a meeting with the president. As Ickes remembered, FDR enthusiastically approved: “I don’t care if she sings from the top of the Washington Monument, as long as she sings!” Ickes went forward with the eagerly anticipated announcement: Marian Anderson would perform at the Lincoln Memorial. ER sent Anderson a bouquet of roses and her apologies for missing the concert. It was Ickes who stood with the singer on the steps in front of Lincoln’s statue, declaring that “in this great auditorium under the sky, all of us are free.” The crowd, seventy-five thousand strong and racially integrated, cheered the secretary, who gave what he would remember as “the best speech” of his long career, “Genius, like justice, is blind… Genius draws no color line.”

Marian Anderson by Annemarie Heinrich, ca. 1937. University of Pennsylvania, Marian Anderson Collection of Photographs. Wrapped in a long fur coat to protect against a biting wind, Anderson made her way to the microphones that relayed her voice to the massive crowd gathered at the Mall as well as to the millions more tuned in on NBC radio. She closed her eyes, took a deep breath, and began the patriotic anthem “America.” Consciously or not, Anderson had subtly changed the third line, usually rendered as “Of thee I sing.” “To thee we sing” was more inclusive, a reflection, perhaps, of the collective endeavor of the integrated, adoring crowd. In all, the ceremony lasted less than an hour, but the powerful symbolism of the day would resonate through the years. Among the individuals who watched it live, Mary McLeod Bethune wrote, history “may and will record it, but it will never be able to tell what happened in the hearts of the thousands who stood and listened yesterday afternoon. Something happened in all of our hearts. I came away almost walking on air. We are on the right track—we must go forward.” Once war broke out between the US and the Axis powers, the DAR temporarily dropped its Jim Crow policy and, in January 1943, allowed Anderson to appear at a benefit concert in Constitution Hall for Chinese aid. But this was merely an exception for the war effort, not a change of policy. The DAR leadership remained resistant to change, banning the African American soprano Hazel Scott, the wife of Harlem’s new Black congressman, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., from its D.C. auditorium in 1945. Finally in 1951, the DAR abandoned segregation at Constitution Hall. In the decades that followed, Anderson appeared regularly at White House events. She sang the national anthem at the presidential inaugurations of Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953 and John F. Kennedy, in 1961. Kennedy nominated Anderson for the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, and President Lyndon Baines Johnson bestowed it on her a month after JFK’s assassination. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter worked with leaders in Congress, including Walter Fauntroy, the first African American delegate in the House of Representatives from the District of Columbia, to award Anderson the Congressional Gold Medal. She was the first African American recipient of the Medal. Anderson no doubt welcomed these formal recognitions, but she also cherished the deep, personal relationship that developed with Eleanor Roosevelt in the wake of the DAR controversy. The singer’s 1956 memoir notes that on a trip abroad, she left ER a note written with soap on a mirror at a concert hall upon learning that the First Lady was expected to appear at the same venue. The two women also met in Tel Aviv and Tokyo as well as at Hyde Park, where Anderson sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the opening of the Roosevelts’ Hyde Park home as a national historic site on April 12, 1946, a year to the day after FDR’s death. _______________________

Explore the original report, The Roosevelts & African American Civil Rights Leaders, which features in-depth stories and additional leaders. DOWNLOAD THE REPORT |

Last updated: January 15, 2024