Last updated: January 13, 2026

Article

The Road Through Scotts Bluff

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 25).

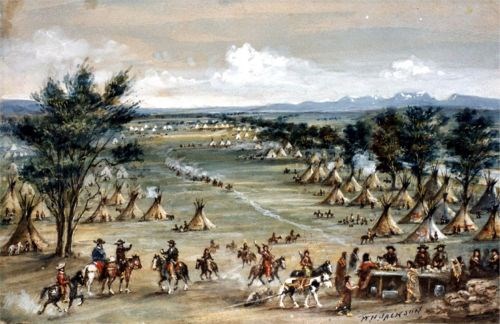

Native Americans

Native Americans were the first human inhabitants of this region. Among the local Indian tribes were the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Pawnee and Kiowa. Parties of Indians broke their travel and camped on the slopes of the bluffs rising from the river. Although the campsites were small, it is known that they worked on projects including knapping various tools from flint or other rocks they had traded for from other tribes.

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 18).

Fur Traders/Mountain Men

Seven fur traders from the Robert Stuart Party were the first white men known to have seen Scotts Bluff. They passed through here on Christmas Day, 1812. Their perilous journey followed a new route, destined to become the Oregon Trail. In the summer on 1826, the first of the trader caravans, led by William Ashley, William Sublette and Jedediah Smith, and possibly including Hiram Scott, passed through the yet unnamed “Mitchell Pass”.

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 151).

Missionaries

In 1834, the Methodist minister Jason Lee and his brother Daniel came to the Oregon country as the first of the missionaries. In 1836, four Presbyterian missionaries, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and Henry and Eliza Spalding, passed by Scotts Bluff on their way to the Walla Walla Valley in Oregon. Narcissa and Eliza were the first white women to pass Scotts Bluff, leading the way for many more.

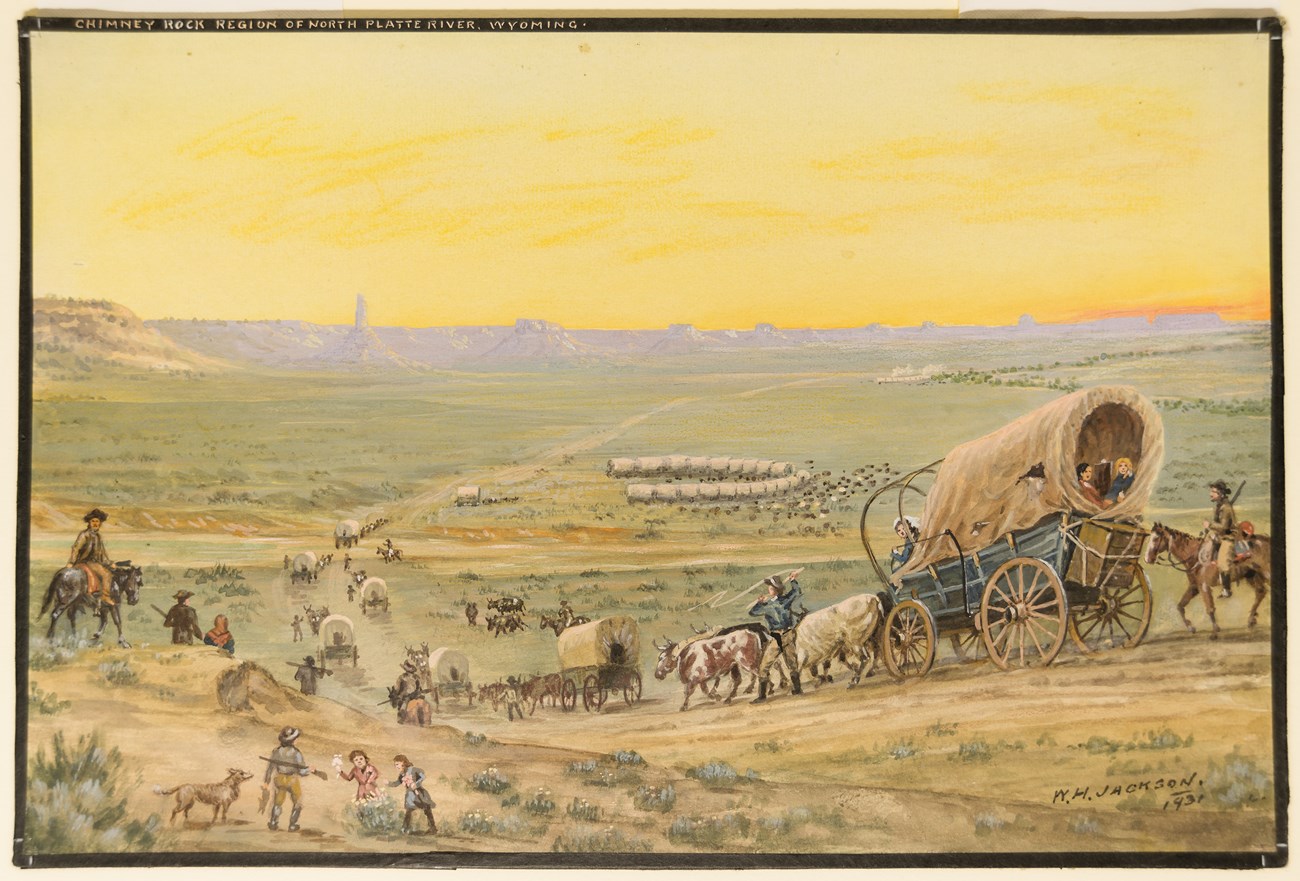

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 278).

Emigrants

Emigrants left from various points along the Missouri River in late April and reached Scotts Bluff around mid-June. Wagon trains travelling on the south side of the river were forced further south by the bluff. During 1841-1869, over 250,000 emigrants traveled through the Scotts Bluff area along the Oregon, California and Mormon Trails. They faced many dangers along the trail, and nearly one in ten emigrants did not survive.

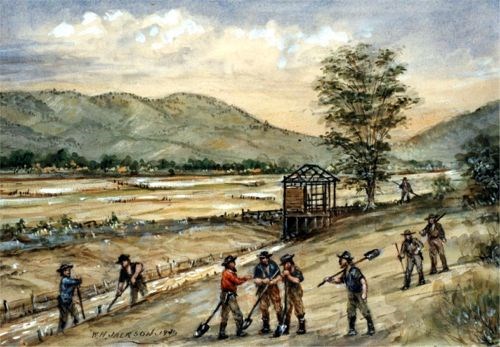

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 42).

49ers

The California Gold Rush began at Sutter’s Mill. On January 24, 1848, James Marshall found shiny metal in the tailrace of a lumber mill he was building for John Sutter. With this discovery, a wave of “miners” headed Westward. The Oregon Trail became the road to California. The earlier wagon trains through Scotts Bluff included men, women and children, but the 49ers were mainly men in a hurry. About 25,000 49ers passed through Scotts Bluff in 1849 and another 44,000 in 1850.

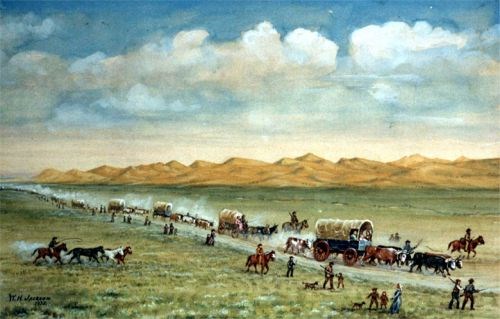

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 26).

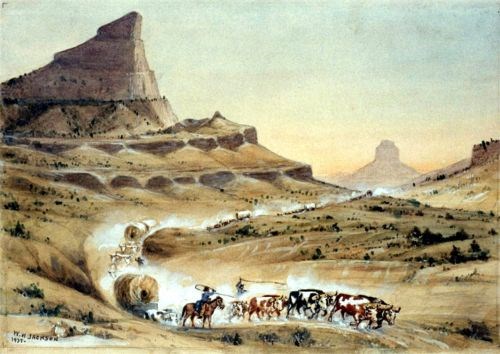

Mitchell Pass

Some Native Americans called Scotts Bluff “Me-a-pa-te”, or “hill that is hard to go around”. Prior to 1850, most emigrants were forced to travel through Robidoux Pass, nine miles south of the river. In 1850, after the pass was widened and filled, wagon trains switched to the new Mitchell Pass route. Although the new pass did not shorten the trip as a whole, it did cut eight miles off the portion they were away from the river. Unfortunately, the new pass was only one wagon wide, forcing the trains into single file. This was not popular due to the amount of dust that was raised.

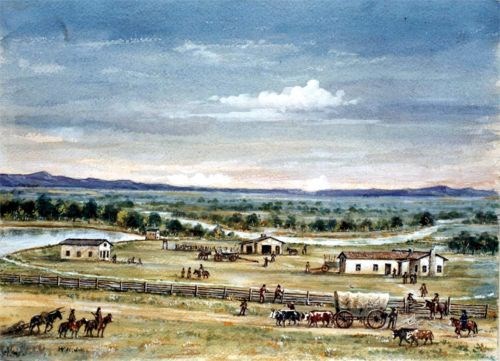

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 28).

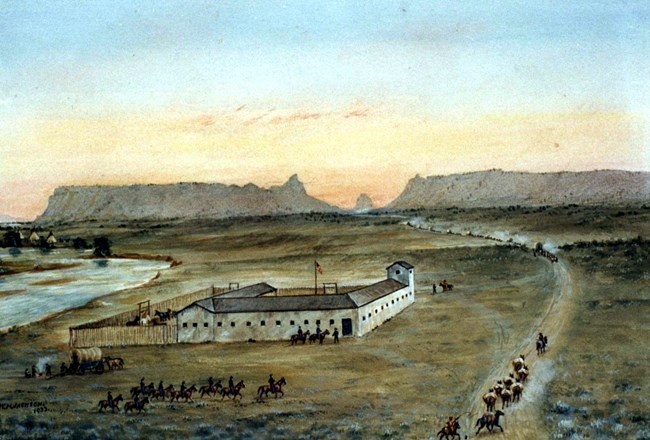

Soldiers

During America’s westward expansion, the U. S. Army established hundreds of outposts throughout the frontier to protect emigrants, serve as staging areas for military campaigns and maintain communication with the West Coast. The closest outpost to Scotts Bluff was Fort Mitchell, located three miles from the pass. Fort Mitchell was the home of the 11th Ohio Cavalry. Although short lived, 1864-1867, Fort Mitchell served as a reassuring force and protection to travelers along the Overland Trails.

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 164).

Pony Express

The Pony Express started on April 3, 1860, heading west from St. Joseph, MO to San Francisco, CA. The route took 10½ days. Each rider rode 75-100 miles twice a week for $50-$150 a month. The Pony Express lasted only 19 months until November 1861, but created an immediate sensation. Stations were 15 miles apart and in the Scotts Bluff area, the stations included Chimney Rock, Melbeta, Ficklin Spring near Scotts Bluff and Horse Creek. The Scotts Bluff station later became the Mark Coad Ranch.

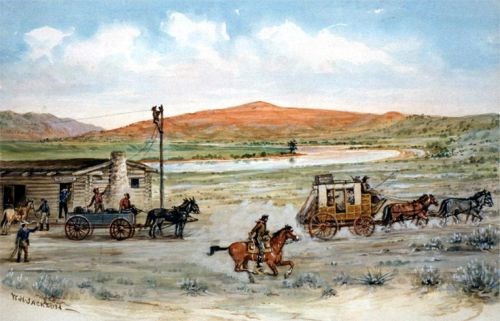

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 148).

Telegraph Lines

The first telegraph line was constructed along the Oregon Trail through Mitchell Pass and ended the life of the Pony Express. The construction of the eastern wire reached Salt Lake City on October 24, 1861, two days before the Pacific wire was completed. The line was known as the Pacific Telegraph Co., headed by Edward Creighton. There was an early telegraph station at Fort Mitchell at the foot of Scotts Bluff.

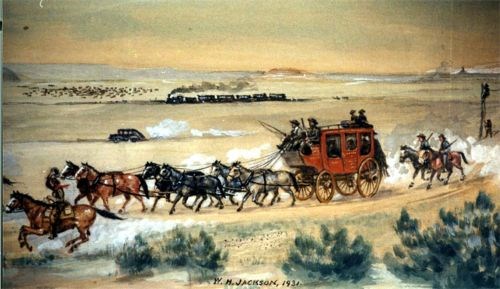

William Henry Jackson; from the watercolor "Westward America" in the Scotts Bluff National Monument Collection (SCBL 37).

Stagecoach Lines

Despite the completion of the telegraph line, there was still a need for stage and mail service between Missouri and California. Beginning in 1861, a daily mail route covered the Overland route between St. Joseph and San Francisco. This daily mail coach ran past Scotts Bluff for one year before being transferred to a more southern route to avoid the Indian troubles in the north. The Overland Stage had a brief life of only six years, as the westward advancing Union Pacific railroad soon ran the stage out of business.

NPS

Railroad

The railroad spelled the doom of the stagecoach lines and the prairie schooner. Although the route finally selected followed the Lodgepole Creek to Cheyenne Pass, the North Platte route by Mitchell Pass was considered. The “iron horse” reached Cheyenne in 1867 and joined the Central Pacific at Promontory Point, Utah on May 10, 1869. This date can be accepted as marking the end of the historic Oregon/California Trail.

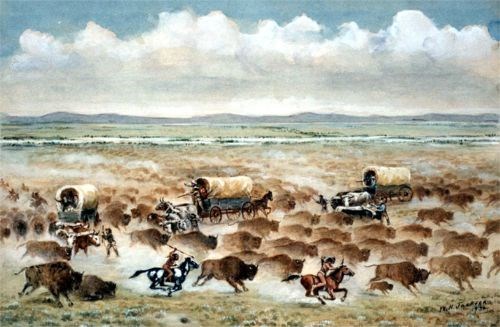

William Henry Jackson; from the Scotts Bluff National Monument collection (SCBL 153)

Buffalo Hunters

The ruthless hide-hunters were effective allies of the US Army in ending resistance of the Plains Indians to the white men advances. The American bison, or buffalo, had been the staff of life for the Indians. Once vast buffalo herds crossed and recrossed the North Platte River. The many expeditions and the emigrants on the Overland Trails killed the huge shaggy beast wholesale. As a result, most of the herds withdrew to the southern Plains.

NPS