Last updated: January 16, 2024

Article

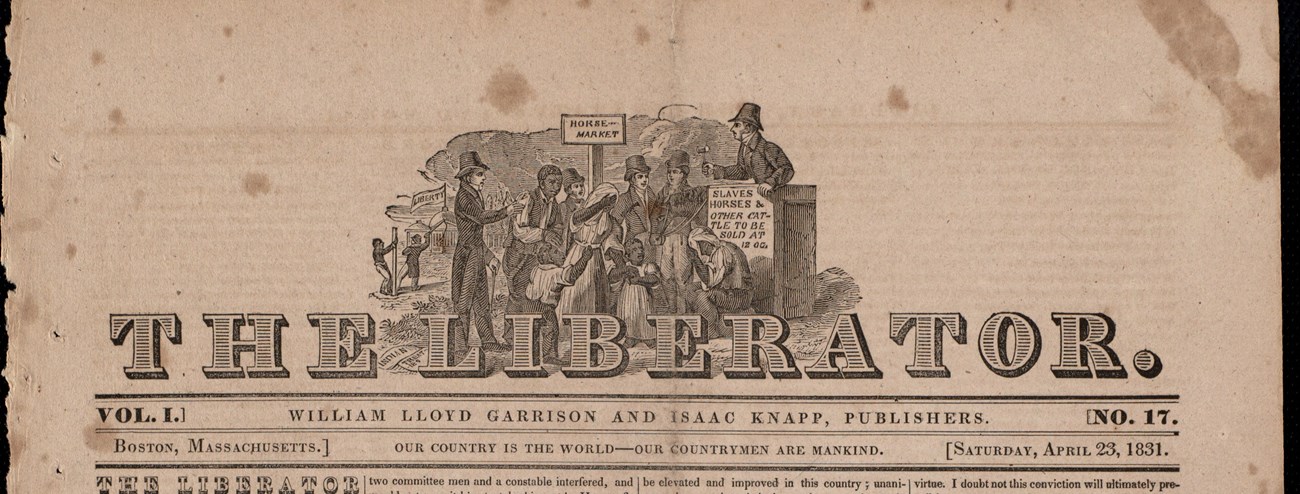

"The Liberator"

Boston Public Library

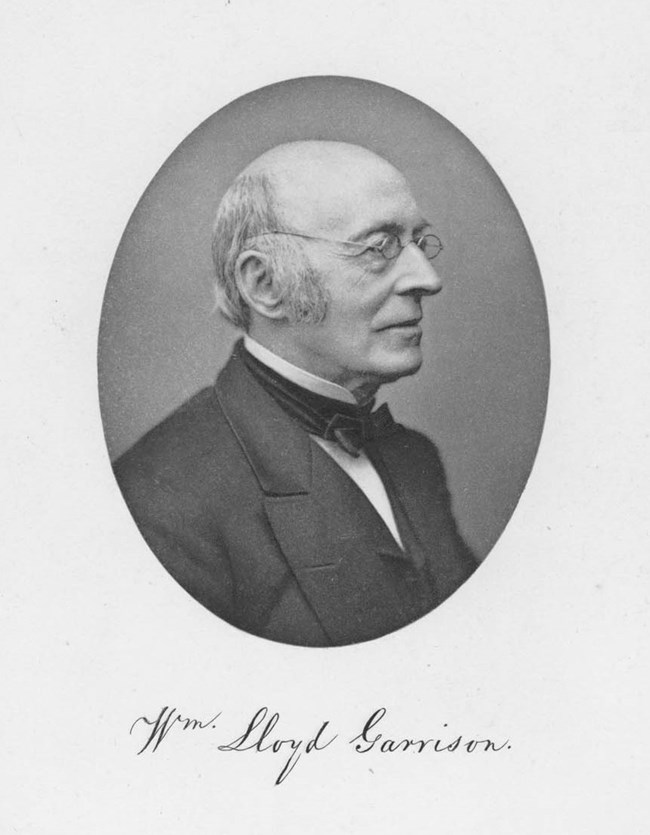

First published on January 1, 1831, The Liberator quickly became the preeminent abolitionist newspaper in the United States. Edited by the fiery activist William Lloyd Garrison, this weekly Boston-based periodical served as a major platform to attack slavery and its supporters, inspire action, and promote equal rights for all. As historian and activist Horace Seldon wrote:

Garrison knew what any organizer today knows; to build a "movement" it is necessary to "communicate", "communicate", "communicate". "Disseminating light" became a primary movement function for the Liberator.1

Massachusetts Historical Society

With Garrison at the helm, his specific beliefs and tactics dominate the pages of the Liberator. His tenets included: calling for an immediate uncompensated end to slavery; attacking both the Church and the Constitution as tools of the oppressors; and advocating for change and racial equality through peaceful moral suasion, meaning appealing to people's morality to influence or change their behavior. Furthermore, Garrison used his paper to pursue other social reform goals, such as women's rights, pacifism, and the fight against capital punishment. In the Refuge of Oppression section of the paper, Garrison often printed writings by those who disagreed with him. This tactic gave him the opportunity to clarify the arguments and serve as a launch pad for his sharp responses.

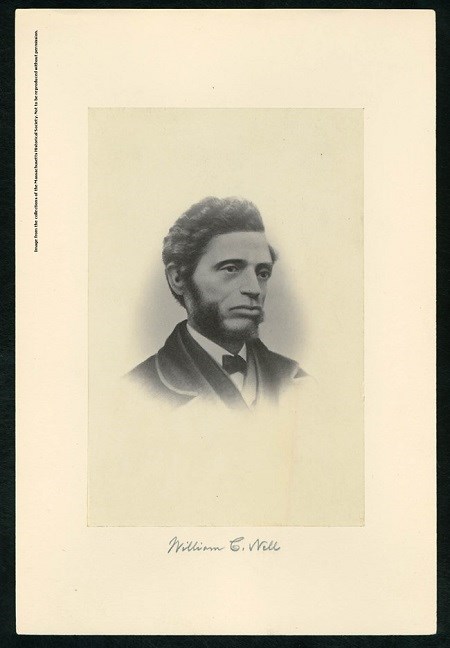

The Liberator drew some of its strongest support from the local Black community. Black leaders including the Reverend Thomas Paul, Reverend Samuel Snowden, and businessman James Barbadoes publicly endorsed the paper while a committee of Black women headed by Elizabeth Riley and Bathsheba Fowler led fund raisers to get it off the ground.2 Black Bostonians and other African Americans throughout the North largely sustained the paper in the early years. These supporters comprised roughly 75% of all subscribers and helped financially support the paper.3 Garrison, in turn, eagerly published articles by local Black writers such as Maria Stewart and William Cooper Nell. In fact, as a teenager, Nell began working for Garrison as an apprentice at the Liberator, learning the skills of a publisher and journalist. He believed, along with Garrison, that the Liberator would create the "revolution in public sentiment" that Black activists sought.4 Nell continued to contribute to the Liberator throughout its entire run, with only a brief hiatus when he moved to Rochester, New York to work with Frederick Douglass on his paper, The North Star.

The Liberator provides an incredible window into the local Black community of Boston, reporting on numerous meetings and efforts in the ongoing fight for abolition and equal rights. There are many references throughout the decades of the paper's existence to community gatherings at the African Meeting House and the Abiel Smith School, both now featured sites of the Black Heritage Trail® and Museum of African American History.

The Liberator also served as an important part of Boston’s Underground Railroad network. The paper reported on fugitive slave cases and assistance organizations such as the New England Freedom Association and the Boston Vigilance Committee. Along with his long time General Agent Robert F. Wallcut, Garrison used the Liberator office as a clearinghouse for donations, clothing, information, and job opportunities. The office also sometimes served as a temporary safe haven to shelter newly arrived freedom seekers to the city.5

Massachusetts Historical Society

The Liberator also served as an important part of Boston’s Underground Railroad network. The paper reported on fugitive slave cases and assistance organizations such as the New England Freedom Association and the Boston Vigilance Committee. Along with his long time General Agent Robert F. Wallcut, Garrison used the Liberator office as a clearinghouse for donations, clothing, information, and job opportunities. The office also sometimes served as a temporary safe haven to shelter newly arrived freedom seekers to the city.5

As an instrument of Garrison's brand of radical abolitionism, the Liberator drew criticism from many pro-slavery writers as well as others. This included anti-slavery activists who did not agree with Garrison's more extreme beliefs and drastic approaches to bringing about societal change. But as Garrison stated in his first edition:

I determined, at every hazard, to lift up the standard of emancipation in the eyes of the nation, within sight of Bunker Hill and in the birth place of liberty...Let southern oppressors tremble-let their secret abettors tremble-let their apologists tremble – let all the enemies of the persecuted blacks tremble...I am aware, that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! no! Tell a man whose house is on fire, to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest-I will not equivocate-I will not excuse-I will not retreat a single inch-AND I WILL BE HEARD”6

And the nation did hear Garrison. He published the Liberator every week for thirty five years, never missing a weekly edition. The paper concluded its legendary run in December 1865, the same month as the ratification of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the United States. As stated in the final issue, the Liberator "will then be discontinued for the reason that the object for which it was started has been accomplished – slavery not only having been abolished by the war for the Union, but also by Constitutional Amendment. What a grand and sublime triumph!"7

As a tool of the abolition movement, the Liberator's impact is immeasurable. It provoked and inspired countless others to take up the cause. As a young Frederick Douglass said, soon after escaping from slavery and moving to Massachusetts:

The paper became my meat and my drink. My soul was set all on fire. Its sympathy for my brethren in bonds--its scathing denunciations of slaveholders--its faithful exposures of slavery--and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution--sent a thrill of joy through my soul, such as I had never felt before!

I had not long been a reader of the "Liberator," before I got a pretty correct idea of the principles, measures and spirit of the anti-slavery reform. I took right hold of the cause...8

Footnotes:

1. Horace Seldon, "A Life of Purpose," A Life Of Purpose | William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator Abolitionist Newspaper (theliberatorfiles.com).

2. Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1998), 109.

3. Donald Jacobs, "William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator and Boston's Blacks, 1830-1865," The New England Quarterly Vol. 44, No. 2 (Jun., 1971), 259-277, 261.

4. Stephen Katrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin, 2012), 52.

5. Kathyrn Grover and Larson Neil, "The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts, 1783-1865" (National Park Service, 2000).

6. Liberator, January 1, 1831, 1.

7. Liberator, December 29, 1865, 2.

8. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself (Boston: The Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), page 116-117. Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself (unc.edu).