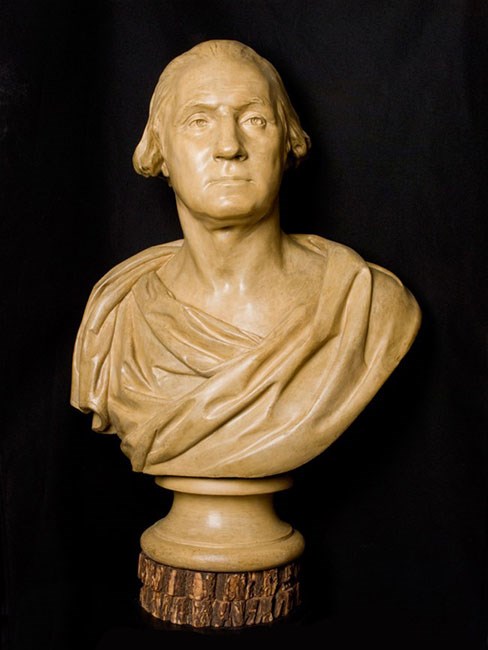

Museum Collection (LONG 4132)

With these words, General George Washington introduced himself to his new army. Washington had arrived in Cambridge on July 2. That evening, he formally took command from Massachusetts General Artemas Ward, met with some of the army’s high-ranking officers, and went to work—joining his temporary housemate and third in command Charles Lee, a professional soldier with a career of military service far exceeding that of any American-born commander, for a ride to examine some of the siege lines around Cambridge. Within two weeks, Washington moved west along the Road to Watertown to the grand Georgian mansion of the evacuated John Vassall. From there he would direct a siege and begin working to shape an army to match his vision. George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 on the Northern Neck of Virginia into a family of middling, but striving, gentry. Although he was the first child of the marriage of Augustine Washington and Mary Ball, George had two older brothers and a sister from his father’s first marriage, and would later be joined by four surviving full siblings. His prospects were abruptly altered in 1743 when Augustine died at just 48 years of age, continuing a family trend of early male deaths that eventually aided George’s rise, placing him in charge of Mount Vernon and its enslaved workers by 1754. In the immediate aftermath, his father’s death meant that 11 year old George would not have the benefit of education in England like his older brothers, a deficit which caused him some degree of embarrassment for the rest of his life. Instead of further development in the classroom, Washington would learn in the real world, traveling throughout the Virginia backcountry as a surveyor. Despite a lack of formal education, the young man did not lack benefactors, notably through his brother Lawrence’s marriage into the vaunted Fairfax family. These connections enabled Washington to embark on a provincial military career which saw him elevated to Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and commander-in-chief of the colony’s forces before his 34th birthday. During the French and Indian War, Col. Washington gained valuable experience as a leader of men and became relatively famous for exploits both good and bad. The biggest break in George Washington’s life came when he married a 27 year old widow named Martha Dandridge Custis on January 6, 1759. The combination of his own wealth with her estate moved Washington in the elite of colonial Virginia society and roughly tripled the number of enslaved people under his control. The next fifteen years were spent running and expanding Mount Vernon, taking care of his new family, and carrying out the civic roles expected of a gentleman of his stature, including election to the House of Burgesses. Throughout the politically turbulent 1760s and 1770s, Washington was present, albeit often silently, for the great debates and resolutions of colonial resistance. By 1774, he was recognized enough to be one of Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress alongside the more famous Patrick Henry. Washington returned to Philadelphia the following May as one of Virginia’s delegation to a renewed Continental Congress. Shortly after convening, Congress’s agenda quickly became dominated by military matters as word spread of hostilities between colonists and Redcoats along the road between Boston and Concord on April 18-19. Washington’s military expertise was unmatched amongst his colleagues and he quickly was put onto key committees as Congress struggled to chart a course in these dangerous new waters. By the middle of June, at the request of Massachusetts officials, Congress assumed responsibility for the defense of the colonies. On June 14, it created the Continental Army from the New England forces surrounding Boston. The following day it selected George Washington, conveniently the only delegate in a military uniform, to take command. Washington, still just 43 years old, was to spend nearly nine months in Cambridge. The task awaiting him was immense: turning a loosely trained collection of fiercely independent New Englanders from a very different military culture into a disciplined fighting force in the image of the very forces he was opposing. Expecting to find a thriving army, he instead found one full of “Boys, Deserters, & Negroes,” people in his mind unsuited to be soldiers, leading him to question the ability of the Revolutionary Cause to sustain an army on its own. At times, he appears to have been driven to despair, writing Joseph Reed in January 1776:

Despite the obstacles, Washington drew upon great reservoirs of strength and dedication to hold the army together. The efforts here in Cambridge to organize the army and to convince soldiers with elapsing enlistments to stay enabled the Revolution to survive its first winter and set precedents it would follow throughout the long war. In March 1776, cannons transported from captured forts in New York by Henry Knox were emplaced on the high ground south of Boston. From there, they could threaten the shipping lanes which were the only means of supply and escape for the British Army in Boston. A British attempt to displace those cannons was cancelled by a storm, leading to the evacuation of the town on March 17, a date still celebrated as Evacuation Day in the area. The Siege of Boston was over. All of these events were, and are, important. Yet, it was the personal experiences Washington had, and the changes they exerted upon him, which would take on the greatest historical importance. For the first time, Washington experienced the frustrations of dealing with the faulty political structures which developed to replace British colonial institutions. Not only did he report to Congress in Philadelphia, but he was forced to interact with, and often beg for assistance from, politicians on the colony, and then state, level where the real power rested. This would hone his political skills and reinforce his nationalist instincts, positions which were well known when he was called from retirement to attend the Philadelphia Convention which produced the Constitution and when he took on the lead role in that new government. For the first time, Washington, an owner of enslaved people since age 11, witnessed men of color functioning as effective and dedicated soldiers. This combined with a correspondence with the talented poetess Phillis Wheatley to cause Washington to accelerate the growth of his uneasiness with the institution of slavery. The frustrations the commander-in-chief felt in the nine months he spent in Cambridge over the inability of his army to carry out an aggressive strategy of attack and the failures of that army in New York required him to adopt a strategy of survival which was completely foreign to his instincts. All of these things combined to spur growth and development in Washington—as a leader, a commander, a politician, and as a person. In the long-term, however, it was the emergence of George Washington as a national leader, in charge of the first national institution in what became the United States, which had the greatest effects. While in this Cambridge Headquarters, he began his transformation from a Virginia gentleman to the key nationalizing figure of the Revolution and the Early Republic. |

Last updated: September 2, 2021