|

FORT UNION

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 2: FROM RUINS TO A NATIONAL MONUMENT

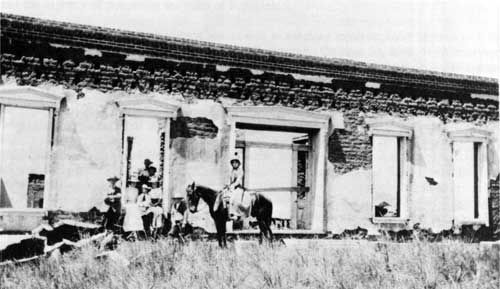

Figure 6. After the abandonment of Fort Union in 1891, the place was

open to tourists and looters.

Their activities accelerated the

deterioration of the buildings.

By 1912 Officers' Quarters had already

become ruins.

Courtesy of Katherine Hand.

On February 21, 1891, singing "There's a Land that is Fairer than This," the Tenth Infantry marched out from Fort Union for good. One non-commissioned person stayed as a caretaker. [1] Three years later, the War Department relinquished claim to the land on which Fort Union stood. Finally both the land and title reverted to the original owners of the Mora Land Grant.

By then the extensive ranchlands surrounding Fort Union had passed into the hands of the descendants of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler of Civil War fame. He purchased the lands from the claimants of the Mora Grant in the mid-1870s. When the military abandoned Fort Union, the Butler-Ames Cattle Company, (later the Union Land and Grazing Company, formed in 1885), inherited the title to the fort. Initially, the Butler-Ames Cattle Company tried to utilize the abandoned fort for economic and social purposes. On January 12, 1895, Paul Butler, Blanches Butler Ames, and Adelbert Ames, owners of the company, entered into a contract with Dr. William D. Gentry of Illinois to lease the buildings to be used as a sanitarium. According to the contract, the owners were responsible for repairing the buildings. For reasons unknown, the contract was never fulfilled. In the next 60 years, the company made no attempt to use the fort except to open it to cattle grazing. [2]

Although the Butler-Ames Cattle Company had little interest in reinhabiting the buildings, quite a few people did make an effort to live in the fort. After Fort Union's abandonment, several soldiers managed to stay there and ran cattle in the area. Nobody ever attempted to evict the squatters, who later moved away. [3] Since troops left almost everything there, Fort Union contained a large quantity of lumber and other construction materials, which interested local residents from the nearby communities of Loma Parda and Watrous. Whenever a family wanted to repair or even to build a house, the people went to the ruins of Fort Union to find what they needed. In Watrous, almost all the windows, doors, and vigas in the houses came from Fort Union. [4] They first took materials from the officers' and company quarters, then from the mechanics' corral, followed by the warehouses, and finally the hospital. Also, curiosity seekers often took items home. Rising above the open prairie, Fort Union invited scavengers and souvenir hunters.

Mother nature was as destructive as vandals. At the beginning unskilled soldiers had built the fort with adobe bricks and unseasoned, unhewn, and unbarked pine logs. Consequently, it decayed rapidly. The buildings of Fort Union required constant repair even during the period of occupation. A military wife, Genevieve LaTourrette, later recalled, "Toward the latter years at Fort Union, the quarters needed renovating badly....Roofs were leaking in the quarters to the extent that we went around with umbrellas." [5] The adobe walls, in particular, were vulnerable to all kinds of weather. After the fort's abandonment, the condition of the buildings deteriorated faster than ever. Along with vandalism, the sun, rain, snow, and wind turned the fort to ruins.

The first serious attempt to preserve the ruins of Fort Union as a historic site came in 1929 when the Freemasons in Las Vegas, New Mexico, called for the establishment of a national monument. Fort Union was the birthplace of two Masonic Lodges--Chapman Lodge No. 95 (later Chapman Lodge No. 2) and Union Lodge No. 480 (later Union Lodge No. 4). On March 28, 1862, some zealous Masons set up a new lodge under the dispensation of the Grand Lodge of Missouri. They named it Chapman Lodge in honor of Lt. Col. William Chapman, who was then in command of Fort Union. Many officers and enlisted men belonged to the lodge and attended the meetings regularly in the "House of the Good Templars." In 1867 the Army requested that the lodge be moved outside the government reservation, apparently for military reasons. The lodge was moved to Las Vegas. In 1874 another group of Masons asked for permission to establish a Masonic Lodge at Fort Union. This time they called it Union Lodge, which met in the fort until 1891. Then it moved to Watrous. [6]

With a purpose to enshrine the birthplace of the Chapman Lodge and the Union Lodge, Masons in Las Vegas became the first to ask for preservation of the ruins of Fort Union. On January 23, 1929, they appointed a four-person committee chaired by W. J. Lucas to "have Fort Union declared a national monument." [7] Taking the issue to Santa Fe, the committee successfully persuaded the state legislature to pass a joint resolution to petition Congress. In Joint Resolution No. 12 of 1929 the legislature of the State of New Mexico respectfully petitioned "the Congress of the United States to set aside this historic site and to preserve and maintain Fort Union as a National Monument." [8]

The campaign for the Fort Union National Monument soon gained support among the lawmakers of New Mexico. On April 20, 1930, Rep. Albert Gallatin Simms of New Mexico introduced a bill (H.R. 11146) in the 71st Congress, asking the Federal Government "to provide for the study, investigation, and survey, for commemorative purposes, of the Glorieta Pass, Pigeon Ranch, Apache Canyon battlefields, and of Old Fort Union in the State of New Mexico." [9] At this time, the nation was suffering the economic woes of the Great Depression. It was hard to imagine that Washington would pay much attention to the ruins of an old fort in New Mexico. Not surprisingly, the bill died in the House Committee on Military Affairs.

Even though the Great Depression temporarily halted work toward the preservation of Fort Union, New Mexico did not give up their struggle for a national monument. Articles on Fort Union frequently appeared in New Mexico's newspapers and magazines. In the mid-1930s the National Park Service also reintroduced hope for the preservation of the fort by showing interest in the ruins of Fort Union. Roger W. Toll of Rocky Mountain National Park drove down to the Mora Valley to inspect the "Proposed Fort Union National Monument" in December 1935. He took some notes and photographs and collected a few published articles. On March 24, 1936, the superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park forwarded Toll's report and gatherings to Washington. [10] Toll's efforts provided the National Park Service with a first-hand account of the condition of the ruins. These actions also gave renewed hope that the fort would be salvaged for future generations to learn from and enjoy.

After receiving Toll's initial account, the National Park Service decided to make an additional study of the fort. In 1937 Edward Steere of the Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings was assigned to write a frontier history of Fort Union. Within a year he finished a 108-page report entitled "Fort Union, Its Economic and Military History." [11] In this well-researched paper, he indicated that Fort Union played an important role in the development of the territory of New Mexico. The study not only provided the Park Service with the first comprehensive history of Fort Union, but also supplied the administrators with information on the urgency for preservation of the site.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

foun/adhi/adhi2.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2001