|

The place we now call Acadia National Park has always been a place for learning. Though, the earliest attempts at colonizing and settling the coast of Maine often boasted of first 'discovering' or 'documenting' something new, through thousands of years of relations with the land and sea, the Wabanaki (People of the Dawnland) gained insights about the natural world far beyond what these european 'explorers' could see. In the early 1800s, visitors and immigrants from Europe came to the region as part of government surveys and naturalist expeditions. Geologists, in particular, traveled here to understand past climate changes and the shifting of glaciers and sea level, including Louis Agassiz, Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, and Florence Bascom. William Stimpson, Addison Verrill, Edward Morse, and Alpheus Hyatt studied the invertebrates of shoreline and seafloor.

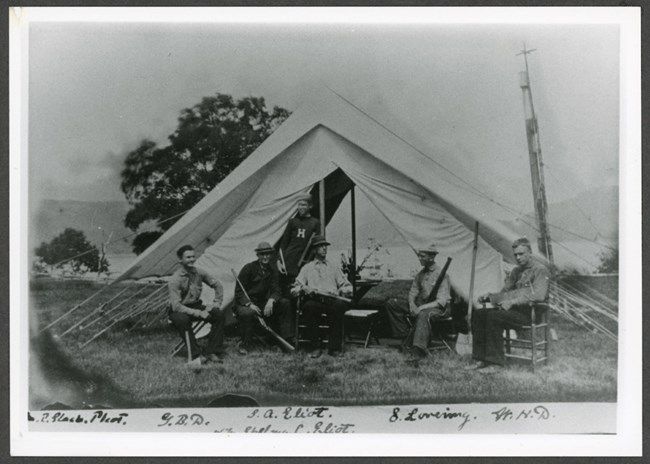

Courtesy of Northeast Harbor Library The Champlain SocietyIn the 1880s, a group of Harvard College students spent summers on Mount Desert Island; the Champlain Society did some of the first recorded detailed inventories of plants, birds, fish, geology, and waters of the island. Their citizen science (science that involves the participation of people who are not “professional scientists”) largely inspired the protection of Acadia as a national park. Their records continued to be used and referenced today to examine the impacts of climate change and other influences on Acadia's natural environment. In partnership with the local Mount Desert Island Historical Society, these efforts have been collected and digitized and will continue to grow over the years. A Park for ScienceWhen Acadia was first established as Sieur de Monts National Monument, the major backers of the park’s creation (George Dorr, Charles William Eliot, John D. Rockefeller, and others) envisioned the park and the surrounding area becoming a retreat or field station for science. At the same time the park was protected, they helped to establish the Jackson Laboratory and Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory, now world-class research institutions focusing on genetics and regenerative biology, respectively.

The Warbler StudyEarly in Acadia’s history, the park hosted foundational research in ecology and geology. Acadia served as the setting for the first popular guide to the intertidal zone and first illustration of an intertidal food web. It has been an important contributor to studies of bird migration and animal ecology. In the 1950s Robert MacArthur studied warbler feeding habits in the park. His study yielded the niche differentiation theory and his main figure from that study has appeared in virtually every ecology textbook since the 1960s. Flying into Science HistoryThe last known nesting pair of Peregrine Falcons was reported on Mount Desert Island in 1956. By the mid-1960s, researchers determined that peregrines were no longer a breeding species in the eastern United States. Nest robbing, trapping, and shooting first contributed to their downfall, followed in the 1950s by ingestion of chemical pesticides and industrial pollutants. Occupying a position high on the food chain, peregrines are still exposed to high levels of chemical residues if they migrate to or eat migrant song birds from countries using pesticides now banned in the United States. As in other birds of prey, ingested chemical toxins accumulate in their bodies, causing reproductive failure and leading to the decline and eventual endangerment of the species. A Living LegacyToday, researchers recognize the value in these early studies, and have begun revisiting some of those data sets early researchers left behind. They are gaining important insights that are advancing science and informing the management of Acadia and other national parks. |

Last updated: February 12, 2022