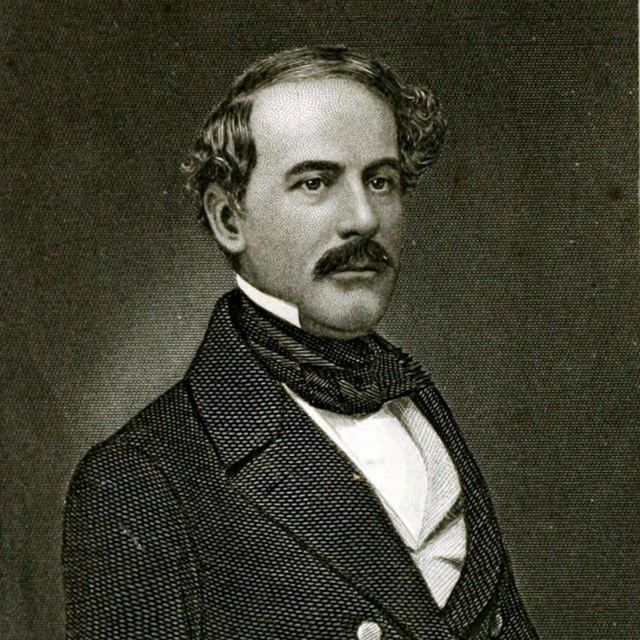

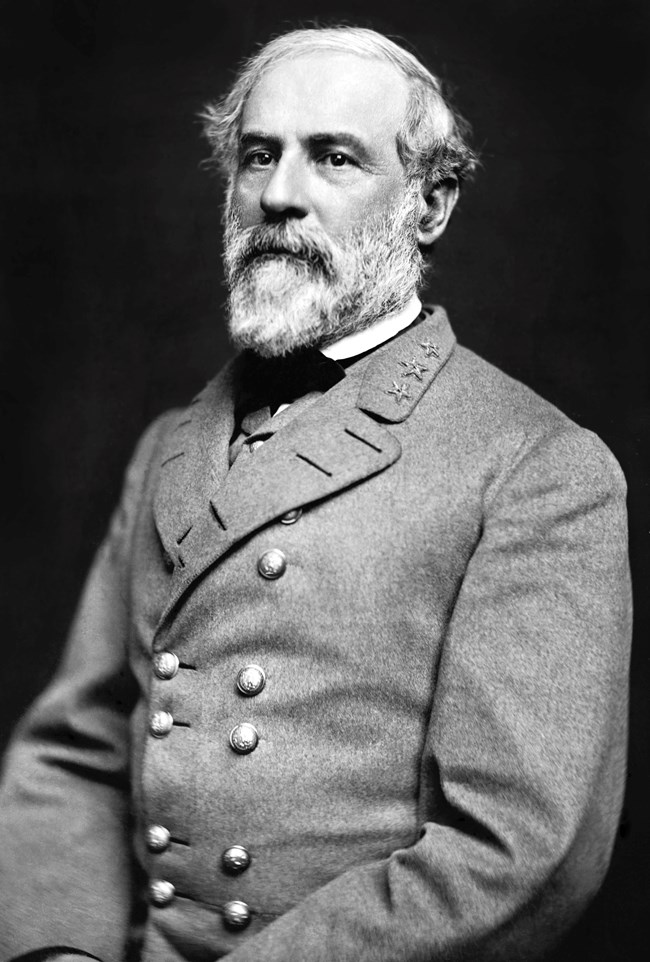

Robert Edward Lee was born on January 19, 1807, into a prominent family at Stratford Hall in Virginia. Soon after Robert’s birth, his father’s poor financial management forced the family to leave Stratford Hall. Moving to Alexandria, Virginia, he met and would eventually marry his distant cousin, Mary Custis, heiress of Arlington House, in 1831. Though he served three decades in the US Army, it was his three years as commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and his post-war career that largely defined his public life. Graduating second in his class from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1829, Lee served more than 31 years in the US Army, including three years as superintendent of West Point in the 1850s. Though his career rarely included combat, Lee gained recognition as a scout in the Mexican-American War. In 1859, he led US Marines to subdue abolitionist John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry. At the time of his resignation in 1861, he was a Colonel. Lee’s military career kept him away from Arlington for most of his adult life. In 1853, he admitted to his wife, “I unfortunately belong to a profession that debars all hope of domestic enjoyment.” [1] Nonetheless, biographers and family memoirs portray a father figure who played with his children when at home and showed concern that they fulfill the social expectations as children of an elite Virginia family. Management of Arlington When Mary Lee’s father, George Washington Parke Custis, died in 1857, Robert E. Lee became executor of his will. The estate included thousands of acres of land, three large plantations, and oversight of nearly 200 enslaved people previously owned by G.W.P. Custis on three different plantations. In an effort to fulfill the Custis will and pay off debts, Lee hired out many of the enslaved people to neighbors. With many of the enslaved people sent to other plantations, by 1860, (according to census data) the enslaved population at Arlington fell from 63 to 38. [2] Lee’s executorship of Arlington House brought his first brush with national attention. The controversy surrounded George Washington Parke Custis’ will. The will stipulated that Lee manumit (free) the enslaved people within five years. However, several enslaved people attested that Custis had promised them immediate manumission, upon his death.[3] The controversy revived in 1859 when three enslaved people escaped because of Lee’s increased work demands and his refusal to grant immediate manumission. Lee had the three freedom seekers apprehended and returned to Arlington House. Some of the enslaved people claimed they were beaten as punishment. During the period of increasing abolitionist sentiment, the story drew national attention as evidence of Southern slaveholding brutality. Lee and his family denied that Custis promised immediate emancipation and directed people to look at the will that Custis had signed. Lee met the court requirements by manumitting the enslaved families of the estate in late 1862. Leadership in Confederate Military Lee’s choice to resign his US Army commission and join the Confederacy became the defining turning point in his life. In December of 1860, he complained to one of his sons about the “course of the ‘Cotton States’” and that he “hope[d] for the preservation of the Union, and I will cling to it to the last.” [4] However, Virginia seceded on April 17, 1861. On April 20, Lee resigned from the US Army, often explaining in letters, “save in defense of my native State, I have no desire ever again to draw my sword.” [5] Days later he accepted a commission as a Virginia general. Upon the wounding of General Joseph Johnston on May 31, 1862, Confederate president Jefferson Davis gave Lee control of the army defending Richmond, with Lee shortly remaming it, the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee’s Civil War experience included battlefield victories and personal loss. Lee became one of the most successful Confederate generals, winning several major battles against larger Union forces at Seven Days, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. Lee’s battlefield victories in Virginia often contrasted with defeats suffered by other Confederate armies. Yet, Lee lamented the occupation of Arlington House by the Union Army. [6] As the war progressed, Lee suffered the death of his daughter Annie. His daughter-in-law also died during the war, while his son Rooney was captured and held prisoner. Lee’s personality became a feature of the war. Lee’s soldiers celebrated his expressions of paternal care and his enthusiasm for fighting, such as his statement at the Battle of Fredericksburg: “It is well that war is so terrible—we would grow fond of it.” Lee often declared his religious observances, stating that victories and defeats were a sign of “God’s Will.” Lee’s officers were nonetheless ever-watchful for Lee’s notable “savage moods.” [7] Lee’s surrender in 1865 was the most significant of the War. Continual fighting and mass desertions saw the Army of Northern Virgina reduced to less than 30,000 soldiers. Lee finally surrendered to US general Ulysses Grant at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865. In his farewell address to Confederate troops, formally known as General Order No. 9, he declared that the army had not been defeated but was “compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.” Lee refused calls to continue a guerilla warfare campaign. His declaration set the framework for how many Confederate veterans perceived the War in the decades that followed. Post-War Career Following the Civil War, Lee was famously subdued in his political commentary. Publicly he promoted restoration of the Union, saying, “I think it the duty of every citizen in the present Condition of the country, to do all in his power to aid in the restoration of peace & harmony, & in no way to oppose the policy of the State or General Governments.” [8] Like many former Confederate leaders, he was indicted for treason in 1865, and faced the possibility of imprisonment and execution. He was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1868. Nonetheless, Lee responded with increasing frustration to Reconstruction policies of protecting African American voting rights and military occupation of the South. In private letters, he told family members, “you will never prosper with the blacks…our material, social, and political interests are naturally with the whites.” [9] He complained that “the South is to be placed under the dominion of the Negroes.” [10] In public, Lee moderated his anti-Black suffrage views. In his 1868 White Sulphur Springs Manifesto, he wrote, “At present the negroes have neither the intelligence nor other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.” (“Gen. Rosecrans and Gen. R. E. Lee, Staunton (VA) Spectator, Sept. 8, 1868) Lee remained a prominent figure in the post-war South. He served as president of Washington College, in Lexington, Virginia. His death in 1870 set off a powerful mourning across the country, North and South. Memorial groups immediately formed to honor Lee. These groups highlighted his superiority in battle, his devotion to duty, and his religious character. Lee is buried in the Lee Chapel on the grounds of Washington and Lee University in Lexington, VA. In 1955, Congress established Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial in honor of his military career prior to 1861 and efforts “to the reuniting of the Nation” after Appomattox.[11]

Notes:

|

Last updated: August 4, 2025