Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

“This is the Age of Statistics”: James A. Garfield and the 1870 Census (Part II)

NPS

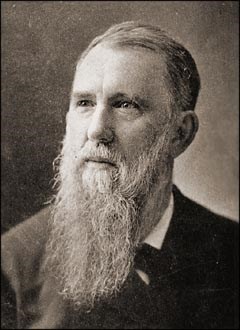

The first session of the 41st Congress adjourned April 10, 1869, four days after James Garfield’s speech proposing comprehensive changes for the Ninth Census of the United States. While members of the House seemed receptive, they were cautious, and wanted to see a revised proposal in legislative language when they returned for their second session in December. So Congressman Garfield took his family home to Hiram for the summer, and returned to Washington to take up the work, along with his committee, of writing a new census law.

On June 9, Garfield wrote to his wife, Lucretia. “The census work has grown to enormous proportions. The Committee works in the Committee room from four to five hours a day, and we have hardly encompassed the field by a furrow, and yet the whole must be plowed and planted. I have never undertaken so Herculean a task.”

The committee room, thankfully, was in the basement of the Capitol, probably the coolest place in the city to meet. Immersed in his new passion, Garfield enjoyed consulting experts and hearing testimony from statistical specialists in many fields, including agriculture, industry, railroads, and mining. To a friend he wrote, “The work of preparing properly classified schedules for the next census is absolutely enormous. The great advance which has been made in the science of statistics in modern nations makes it necessary to go over a large field of investigation in order to bring our Census up to the latest standards of excellence.” By the end of July the committee had completed its investigations and a draft report was written.

Garfield learned a lot while chairing the census committee, and he was happy to share what he had learned. He spoke to the American Social Science Association’ annual meeting. They, no doubt, were expecting political boilerplate, but Garfield surprised them with a sophisticated speech about the evolution and importance of statistical analysis. While he talked about the 1870 census bill in particular, he also suggested that statistics would, and should, inform the writing of history, anticipating the mid-twentieth century trend toward social history and quantitative analysis in historical understanding. That autumn Garfield collaborated with his good friend, Burke Hinsdale, on a census article contributed to Johnson’s New Universal Cyclopedia. In Garfield’s collected works, which were edited by Hinsdale, the article is thirty-two pages long, beginning with an “alleged” Chinese census “more than twenty centuries before the Christian era,” and ending with the ninth United States census.

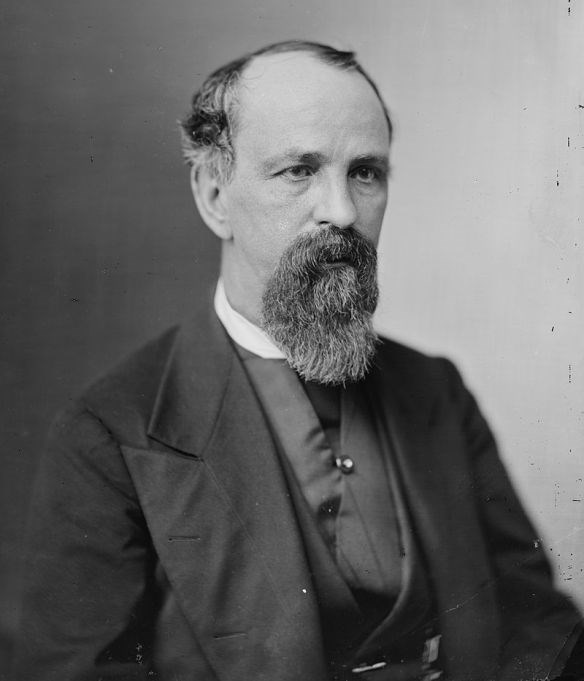

University of Michigan

The bill then moved to the Senate, where it was referred to a committee headed by Roscoe Conkling of New York. That committee promptly dropped the House-passed bill and reported one that Garfield said would, “if it prevails,. . . give us the old law without any of the improvements of the new bill. . .A desire to retain the Marshals (as enumerators) and thus retain the patronage in their hands seems to be the motive with many Senators.” Garfield’s bill died in the in the Senate, and the 1870 census was conducted under the same rules that had applied for the counts in 1850 and 1860.

The 1870 census was not “far more interesting and important than any of its eight predecessors.” But the next one was. With the House of Representatives controlled by the Democrats, a new census bill, virtually identical to Garfield’s, was passed. Samuel S. “Sunset” Cox managed the legislation in the House, and graciously acknowledged the vital work that James Garfield and his committee had put into the census question ten years before.

Library of Congress

June 1, 1880 was, under the new census law, the day that enumerators would fan out to neighborhoods across the country to count the American people. They had a prodigious task. The new census form asked for vastly more information than those of the past. On the population schedule census takers were to record the name of each person in the household, each person’s relationship to the head of the household, and everyone’s age, sex, color, and occupation. The form also asked for everyone’s birthplace and the birthplace of each person’s parents, if a person was deaf, dumb, blind or insane, permanently crippled or temporarily disabled by illness or injury. It also inquired about education level, school attendance, and ability to speak and write English.

On that day enumerator E. C. French arrived at the Garfield’s home in Mentor, and recorded all the required information for James Garfield, his wife and five children. Since their home was also a farm, he then completed a farm schedule documenting its extent and value. There must have been some misunderstanding, since we know the Garfields owned just under 160 acres. The census recorded 135 acres of tilled land, 65 acres of permanent meadow, and 20 acres of woodland—220 acres. The farm was valued at $18,600 for land, buildings and fences, $400 worth of implements and machinery, and $1,200 in livestock. The estimated value of farm production in 1879 was $17,300. The family owned four horses, 15 milk cows and nine other neat cattle, and four new calves. In 1879 six cows were purchased, eight sold living, 11 slaughtered, and one went missing! 7,000 gallons of milk were sold. There were 11 sheep and three lambs, 156 swine, and 50 hens that produced 200 dozen eggs. Crops included barley, Indian corn, rye, wheat and half an acre of potatoes. There were four acres of apple trees, and two acres of peach trees—550 trees in all.

Lake County, Ohio Historical Society

On the same day, June 1, 1880, Helen M. Wipple, an enumerator for Washington D.C., completed a population survey at the Garfield’s home in the capital. It lists James and Lucretia Garfield, their five children, and Mary McGrath, a 25 year old servant who was born in Ireland. It would appear that James Garfield’s family was counted twice on the 1880 census. Even with inevitable errors, this census was what Congressman Garfield had envisioned when he had “gone mad on the subject of statistics” nearly a dozen years earlier.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, September 2019 for the Garfield Observer.