Last updated: July 17, 2024

Article

Growing a Legacy: Restoring Manzanar’s Historic Landscapes After Tropical Storm Hilary

NPS Photo/Jeff Burton

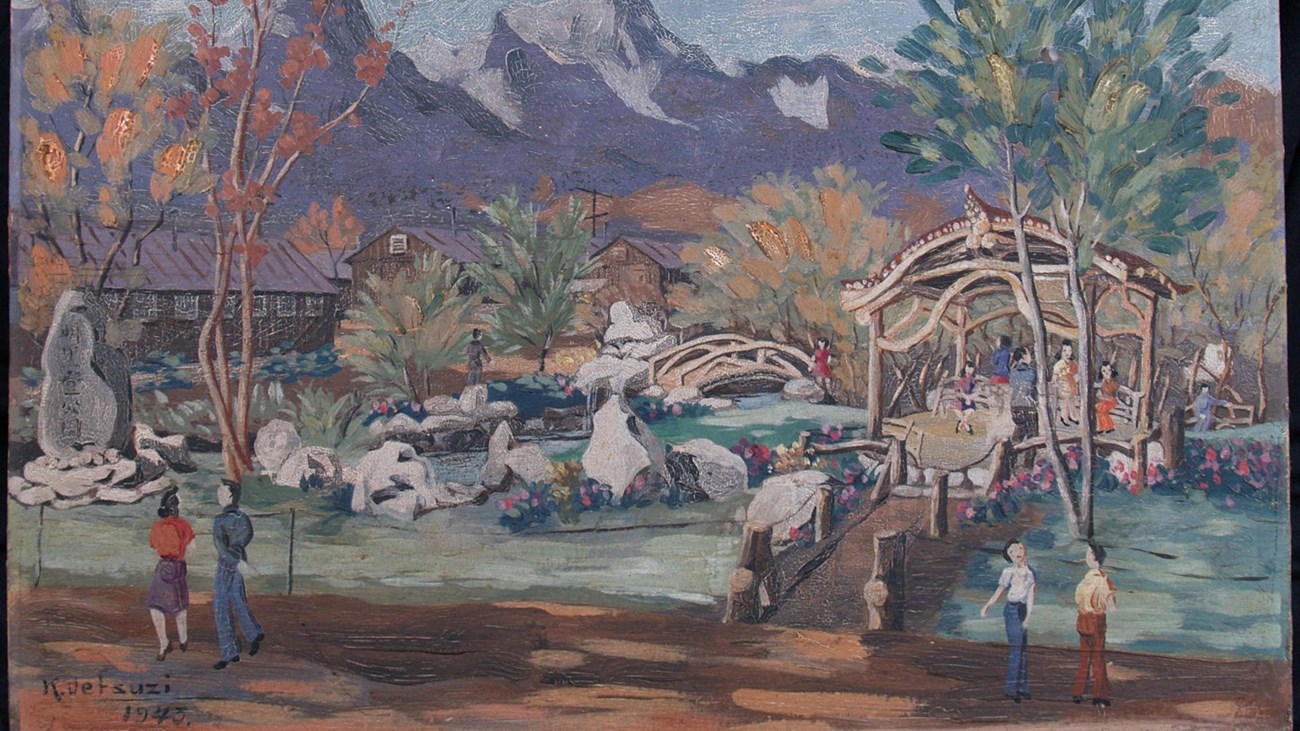

“We are portraying a tough time in history. I’m here to show how the people [incarcerated at Manzanar] made their life better,” says Dave Goto, arborist at Manzanar National Historic Site. Dave has been awarded a Regional Cultural Resource Award for his role in restoring the historic Japanese gardens at Merritt Park and the Wilder Apple Orchard in 2023. A grandson of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated at Manzanar, Dave sees his work as an important legacy. While he is working to care for the garden that incarcerees built, and the same fruit trees they tended, he is also setting up a legacy of care for future NPS stewards to continue.

To Make a Home in the Desert

To be an arborist at Manzanar, Dave must understand the needs of the plants in the ground as well as the history of the landscape they grow in. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, leading to the incarceration of 110,000 Japanese Americans. To carry out the order, the government established ten “War Relocation Centers” in the west. Manzanar, located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains in remote eastern California, was the first to open. Without due process, the U.S. government imprisoned 11,070 Japanese American citizens and Japanese immigrants here during WWII.1Enclosed by a barbed wire fence and eight guard towers, Manzanar had barracks, a mess hall, recreation hall, laundry facilities, and bathrooms. Also within its boundaries were several orchards, including the Wilder Apple Orchard, from the early agricultural days of the Owens Valley. Over time, those incarcerated at the site created numerous gardens and even a park in an attempt to a foster sense of home and community. It is Dave’s job to restore the orchards and Merritt Park.

Today, the historic fruit trees are over 100 years old. In the early 1900s, Romeo Wilder planted pear, apple, and peach trees on land that would later become part of the incarceration site. The agricultural economy of the Owens Valley was short lived, though. The city of Los Angeles bought up the land to protect an important source of water for its residents, causing the fruit orchards to dry up and the residents of Manzanar to move away. The trees, however, remained. Since 2006, the park has rehabilitated two pear orchards. Dave has grafted and raised fruit tree seedlings with his own hands, helping to preserve Manzanar’s heirloom fruit varieties.

Honoring His Family History

Dave grew up knowing that his family had been incarcerated at Manzanar. Many of them were there for a year and a half before they were transferred to Topaz (Utah) or Poston (Arizona). One of Dave’s great uncles was the doctor at Manzanar. Only his grandfather escaped, moving to Wisconsin because he did not want to be imprisoned.

His family members had different experiences and memories of being at Manzanar. One great aunt would curse anytime Dave brought it up. The memories were “too soon and too bad,” he explained. Another great uncle, who was a child at the time, said it was like being at summer camp. He could play games all day and go from one mess hall to the next. That memory is a testament to the sense of normalcy and community that incarcerees worked hard to create for their children during the war.

Tropical Storm Hilary

By August 2023, Dave had completed over 90% of the Orchard Management Plan and was a couple weeks from finishing the restoration of Merritt Park. Then Tropical Storm Hilary struck.

Tropical Storm Hilary

By August 2023, Dave had completed over 90% of the Orchard Management Plan and was a couple weeks from finishing the restoration of Merritt Park. Then Tropical Storm Hilary struck.

NPS Photos/Jeff Burton

NPS Photo/Jeff Burton

Initially, Dave estimated that the storm damage set back restoration efforts by at least six months. But the park went to social media and soon the community rallied to help. Dave supervised 39 volunteers who spent nearly 1,000 hours digging out Merritt Park on the weekends in October to November.3 By mid-November, NPS was able to announce that Merritt Park had been unearthed and most repairs completed. “These people are great, man. I don’t understand how they do it,” said Dave, reflecting on the volunteers’ herculean effort. “That talks to the spirit and the connection of Manzanar to these people. And that really gives me fuel in my fire to do a better job, just day-to-day.”

NPS Photo/Jeff Burth

A Place of Quiet Reflection

More than 40 years after Manzanar closed, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, acknowledging “a grave injustice was done to both citizens and permanent residents of Japanese ancestry by the evacuation, relocation, and [incarceration] of civilians during World War II.” Established in 1992, Manzanar National Historic Site serves as a reminder of that mistake. Now, thanks to the efforts of Dave, the NPS, and many volunteers, Manzanar’s landscapes serve as places of quiet reflection.

If you visit Manzanar National Historic Site in the fall, you might be surprised by a box of fresh pears or apples in the visitor center. In addition to sharing the fruits of his labor with park visitor, Dave shares the harvest with local non-profits and Tribes. “I actually make them sick of pears!” He laughs. “But that just shows that even though these trees are over 100 years old, they’re still producing very desirable fruit.” Dave see the payoff for his work as still being down the road, once the plants in Merritt Park leaf out and the orchard trees grow large. He’s in it for the long haul.

1 National Park Service, Cultural Landscape Report, Manzanar National Historic Site, 2006, p.1.

2 Ibid, p. , p.116.

3 Manzanar NHS social media post, November 13, 2023.

1 National Park Service, Cultural Landscape Report, Manzanar National Historic Site, 2006, p.1.

2 Ibid, p. , p.116.

3 Manzanar NHS social media post, November 13, 2023.