Last updated: June 1, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #24: Fire Away!

In the 1930s the National Park Service (NPS) fire-suppression policy received a boost from Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) funding. CCC enrollees built roads, fire breaks, fire trails, lookouts, telephone lines, and guard cabins in national parks across the country. Even as this infrastructure was being built, another significant effort was underway to improve how quickly forest fires could be detected and suppressed before they spread and engulfed large areas of forest. The tool used to accomplish this was a camera—a very special camera.

The Spark of an Idea

The US Forest Service (USFS) began its planning project in 1931. One phase of the project involved taking oriented panoramic photos from existing lookout stations or proposed lookout station locations. Their focus was national forests in Oregon and Washington, but they also worked cooperatively with the NPS, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and state foresters where additional detection coverage was beneficial to the USFS. Junior Forester Albert Arnst was project lead.

Following testing of equipment and methodologies in 1932, the panoramic photograph project began on June 11, 1933, with money from the CCC program. Arnst's crew of CCC enrollees consisted of Lester M. Moe, Robert M. Snyder, Robert L. Cooper, James Rittenhouse, William Birchall, and Reino R. Sarlin. Most were forestry students at Oregon State University or University of Washington.

A Custom Camera

Panoramic photographs were taken with cameras designed by William B. Osborne, Jr., USFS senior regional fire inspector. Osborne joined the USFS after graduating from the Forest School at Yale in 1909. He was responsible for the first lookout tower in the Northwest (1911) and the first central fire-dispatching system (1913). He is best known for creating the Osborne firefinder, a map mounted on a rotating steel disc with brass sighting mechanisms that allowed fire lookouts to accurately map forest-fire locations. Leupold-Volpel & Company began making the Osborne firefinder in 1913. It quickly became a standard piece of fire-detection equipment and is still available from other manufacturers today. NPS fire lookout manuals in the NPS History Collection include detailed instructions for setting up, maintaining, and using the firefinder.

Osborn’s camera was a photo-recording transit that took oriented panoramic photos from lookout stations. In 1932 Leupold-Volpel & Company made four cameras based on his specifications. The camera combined the features of an engineering surveyor’s transit and a camera. The tripod head included a movable azimuth ring with graduated degrees from zero to 360. At the lookout station, the camera was oriented with the help of the Osborne firefinder. The equipment (camera housing, lens, tripod head, and tripod) weighed about 75 pounds.

Crater Lake and Mount Rainier national parks were among those visited by Arnst’s team. Money ran out for the USFS project in 1935. The NPS purchased its own Osborne camera (the sixth one to be made) in 1934. That year photography began in several California national parks, including Yosemite, Sequoia, and Lassen Volcanic national parks and Pinnacles National Monument (now a national park).

Lester M. Moe

Lester Maynard Moe was born January 21, 1910, in Portland, Oregon. His parents were Louis Moe and Marie Karlsen Moe. He was a graduate of the University of Oregon and completed post-graduate work at the University of California.

Moe left the USFS panoramic photo project after the 1934 field season. He got a job working for the NPS as a junior forester in 1935. Given his previous experience, he was assigned to complete the documentation for NPS lookouts or proposed lookouts. Over four years he documented 200 sites in at least 26 national parks and monuments across the country.

In 1938 an article in the Park Service Bulletin proclaimed the project was done and noted,

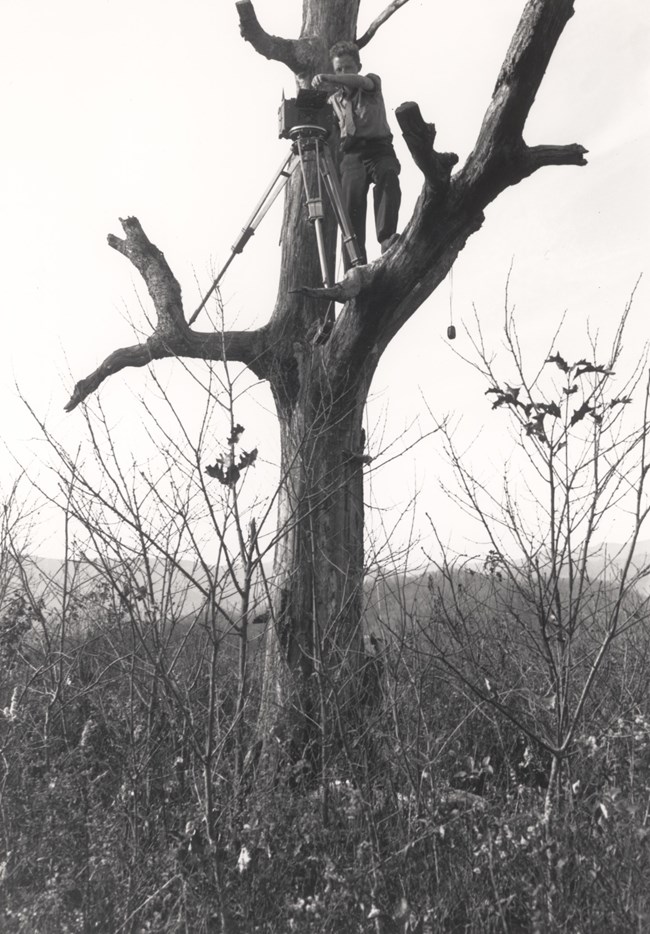

The work entailed many hardships not only in packing the necessary equipment weighing upwards of 100 pounds to lookout points, but also in climbing trees, poles, temporary towers, or roofs of lookouts with the equipment and facing the extreme winds that occur so frequently at high elevations.

Safety gear is conspicuously absent from all available project descriptions.

Although the photography project ended, Moe’s NPS career continued. According to his engagement announcement, Moe was stationed at Yosemite National Park in 1938. On April 2, 1939, he married Nelle-Terry Van Vechten. At the time, his title was assistant statistician in the forestry division. The Moes went on to have a daughter and two sons.

Moe was hired as a ranger at Yosemite National Park on June 1, 1940. He was furloughed from the park on November 10, 1942, to serve in the US Navy during World War II. He returned to his ranger position on December 10, 1945. It’s unknown what additional training he had, but he transferred to Yosemite’s engineer department on July 8, 1946. By January 1, 1947, his title was chief engineering aid (civil). He left Yosemite briefly from May 10 to November 20, 1949, for Mount Rainier National Park. He returned to Yosemite and worked in its engineer department until he retired from the NPS in 1966.

Lester M. Moe died August 27, 1990, in Merced, California, age 80. Nelle-Terry, his wife of 39 years, died the next day.

Getting Technical

The photograph above provides a basic guide to reading each photograph. Each print features identification data including the name of the station, location, photographer, date taken, printed and numbered azimuth (compass readings) scale, and a level line.

Three standard photo setups were taken at each lookout. Each showed a 120-degree sector of the azimuth circle as seen from the observation point. Time of day and the sun's position determined when each photo was taken. Typically 300° to 60° was taken around noon, 60° to 180° was taken around 3 pm, and 180° to 300° was taken around 9 am. Together they gave a 360° view. Moe's panoramic photos were usually taken using panchromatic (abbreviated "PAN" on the images) and infrared ("IR" on the images) films. Panchromatic film is normal black-and-white film. Infrared film absorbs wavelengths differently from traditional film. As a result, healthy deciduous vegetation typically appears very light or nearly white, while healthy coniferous vegetation appears in gray tones. Dead or dying vegetation appears black. Water is very dark and smooth in contrast with the surrounding land. Moist soils also appear in dark tones, while dry soils appear in lighter tones. Examples of both panchromatic and infrared images are given below.

It took almost a full day at each lookout to get the photographs. Add in travel time to and from the lookout station and the difficulty in reaching most of them, and the significance placed on obtaining these images becomes clear.

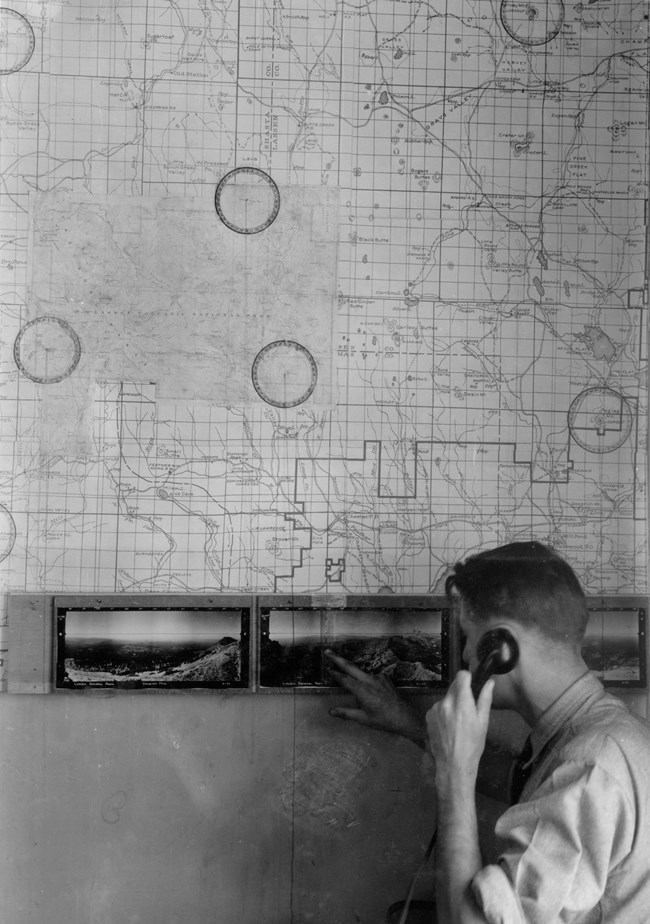

The 5" x 13" prints were mounted in three-fold cardboard “albums.” The photos used were contact prints, not enlargements. A separate vertical angle scale was provided to indicate plus and minus angles with respect to the imprinted level line. Mounted sets of photos were provided to all field personnel with fire-control responsibilities.

In addition, the “seen areas” in the photographs were mapped onto half-inch base and topographic maps out to three distances. The 15-mile radius indicated maximum visibility during pre- and post-fire season conditions. The 8-mile radius indicated visibility during normal summer or fire-season conditions. The 5-mile radius indicated visibility during emergency or bad fire-weather conditions.

Until 1960 the Branch of Park Forest and Wildfire Protection in the NPS Washington Office kept a central file of the negatives and sent additional prints to parks on request. As requests dwindled, however, the usefulness of a central file of the images was questioned. Moe's collection was split apart. The negatives and any remaining prints were sent to NPS regional offices. Over time many regions sent the images to parks. Some, like Yosemite National Park, have made scans of their panoramic prints available online.

The NPS History Collection doesn’t have the panoramic camera made for the NPS (we wish we did!). However, we do have a small collection of the 1930s panoramic photos representing some of the lookouts at Crater Lake, Death Valley, Mount Rainier, and Sequoia national parks.

Take II

When taken, the panoramic photos were invaluable tools for the fire management practices of the day. They could also be used for other purposes, including preliminary locations of roads and trails and visual reference for other management and administrative purposes. Today the photos are more than just relics of NPS fire-management practices or nice scenic images. In addition to fire-management uses, the images provide information about historic roads, trails, and structures; changes in vegetation and landscape; altered geomorphology; and other features of scientific, management, and administrative interest.

In 2007 the NPS partnered with USFS to recreate Moe’s images in Yellowstone and Glacier national parks using the same photo-recording transit. This retake project and others like it provide insights into the ways the national parks changed in the intervening 70 years—and into the future.

Sources:

--. (undated). “William Bushnell Osborne, Jr.” Accessed April 29, 2023, at https://foresthistory.org/research-explore/us-forest-service-history/people/national-forests/william-bushnell-osborne-jr/

--. (undated). “Osborne Fire Lookout Panoramas.” Accessed April 29, 2023, at https://maps.tnc.org/osbornephotos/index.html

--. (1937, September 14). “Panoramic Photos Taken of Mountains.” Visalia Times-Delta (Visalia, California), p. 3.

--. (1937, September 24). “Photographic Work Completed in Park.” Visalia Times-Delta (Visalia, California), p. 3.

--. (1938, June). “Panoramic Picture Project Completed.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. VIII, No. 4, p. 6.

--. (1938, October 27). “Betrothal Announced.” Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California), p. 10.

--. (1939, February 10). “Photos Taken of National Park System." The American Progress (Hammond, Louisiana), pg. 13-14.

--. (1939, February 14). “Photographing of Forest Gets Done.” Rapid City Journal (Rapid City, South Dakota), p. 4.

--. (1939, February 24). “Photos Help in Fighting Fires.” The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), p. 22.

--. (1939, March 36). “April 2nd Set for Nuptial Ceremony.” Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California), p. 48.

--. (1938, May). “Married.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. IX, No. 4, p. 29.

--. (1990, August 30). “Nelle-Terry Moe, Lester Moe.” Merced Sun-Star (Merced, California), p. 4.

Ancestry.com birth, death, marriage, and census records accessed April 27, 2023.

Arnst, Albert. (1985). We Climbed the Highest Mountains. Portland, Oregon: Fernhopper Press.

Arnst, Albert. (1985, September). “We Climbed the Highest Mountains.” Timber-Lines (US Forest Service Newsletter), Vol. 26, pg. 27-28. Accessed April 27, 2023, at file:///C:/Users/NJRUSS~1/AppData/Local/Temp/1/MicrosoftEdgeDownloads/51df6144-35e0-4da3-bd63-909851407b0a/TimberLinesVol26.pdf

Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Bingaman, John W. (1961). Guardians of the Yosemite. Accessed April 27, 2023, at https://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/guardians_of_the_yosemite/second_decade.html

Kresek, Ray. (2007, January 16). “History of the Osborne Firefinder.” Accessed April 27, 2023, at http://www.nysforestrangers.com/archives/osborne%20firefinder%20by%20kresek.pdf

Tags

- crater lake national park

- death valley national park

- mount rainier national park

- pinnacles national park

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- nps history collection

- nps history

- hfc

- fire

- photography

- fire and aviation management

- fire history

- fire management

- fire tower

- lookout