Last updated: May 8, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #48: Canned Plants

Although the National Park Service (NPS) History Collection doesn’t include natural science specimens, it does have objects that reflect how scientists do their jobs to protect and manage park natural resources over time. One example—called as vasculum—was used by NPS botanists to collect plants to press, dry, and preserve plants for museum collections known as herbaria. Our vasculum also has another surprising connection to NPS history.

Gather Ye Rosebuds (and Other Plants)

Vascula (the plural of vasculum) are containers used to temporarily store plant specimens during fieldwork. They carry the plants and keep them in good condition until the collector can get them back to where they are studied, pressed, and mounted—or in some cases replanted in a new location. The use of metal vascula has been documented from the late 1700s, although the term itself didn’t become popular until the early 1800s. By the 1850s they were a common part of the botanist’s toolkit. They were made in many shapes and sizes, but a cylindrical can designed to be carried horizontally was popular.

Metal vascula remained popular until the mid-1900s. As lightweight and inexpensive plastics became increasingly common after World War II, however, they fell out of favor. In their fieldwork today, most botanists use plastic containers of various sizes or zipper-sealed plastic bags.

Using a Vasculum

Ned Burns, chief of the NPS Museum Division, described using a vasculum to collect plants in his 1941 Field Manual for Museums, the precursor to today’s NPS Museum Handbook. He acknowledges the value of herbaria collections for parks but noted, “Collecting is an art in itself and should not be attempted by the uninitiated without a knowledge of how, when, and what to take.”

Burns accepted that what was necessary equipment rather depended “somewhat on the distance the collector may be from headquarters.” For distances under two hours, wet newspapers wrapped around the plants might be sufficient, but “a vasculum is the best receptacle in which to carry specimens for a few hours.” He recommended both a vasculum and a plant press for extended trips, writing,

The vasculum is an oval tin box about 16 inches long, 8 inches wide, and 6 inches deep, with a cover that occupies nearly the whole of one side. Its weight is approximately 3¾ pounds. There is usually a ring at each end for shoulder straps and sometimes a small separate compartment at one end in which the more delicate flowers can be placed. On hot days a wet newspaper should be inserted as a lining to the box to offset the increased evaporation. If the vasculum is painted white or aluminum, it will avoid absorption of the sun’s rays and preserve specimens in fresher condition.

Burns went on to give advice for recording locality and other collecting information, pressing and drying plants, labeling specimens, and other preservation techniques common at that time.

New Deal Connections

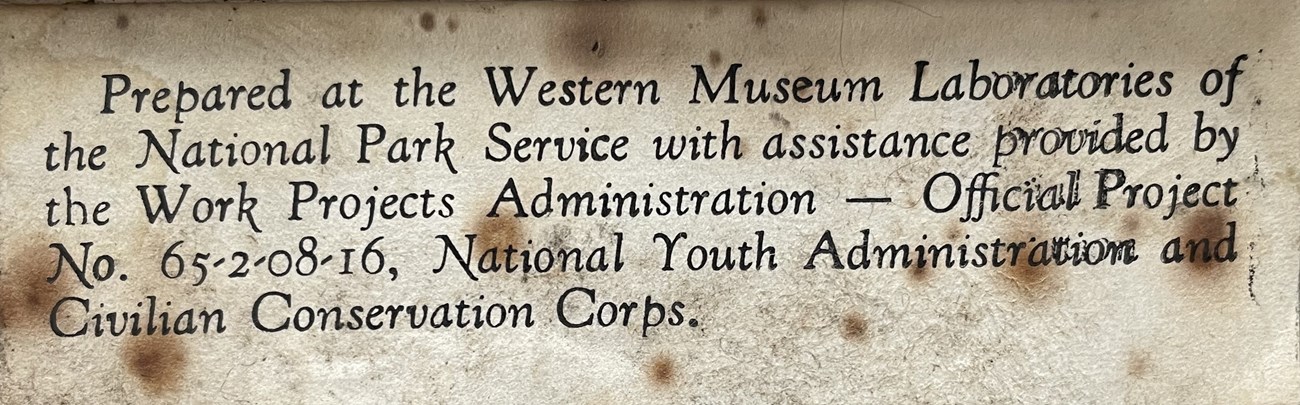

Although the vasculum in the NPS History Collection represents one tool that NPS botanists used to study park plants, it has another significant historical association: It was made by Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and National Youth Administration (NYA) enrollees at the NPS Western Museum Laboratories (WML) in Berkeley, California.

Using these New Deal labor sources, the WML made a range of equipment for natural science collections in parks. Examples include storage cabinets for bird and mammal study skins, geology specimens, insect collections, and herbaria (plant collections); plant presses; traps for birds and small mammals; and celluloid tubes for storing mammal and bird specimens and boxes for skulls. Most of these products were free to parks, although the cost of materials was usually required for cabinets. The WML also offered a free herbarium mounting service.

The first WML-made vasculum was a special order for Glacier National Park but beginning in January 1939, they became available for general distribution through WML's Miscellaneous Products Available to National Parks and Monuments from the Western Museum Laboratories. The catalog describes it as "made of heavy-gauge sheet metal reinforced at all edges. Hinge and ring are slotted through and securely soldered so that the cover is strong and easy to operate. Forest green color. Adjustable shoulder straps." The catalog also notes, "This vasculum is comparable in quality to regular vasculums for sale at biological supply houses."

The Importance of Herbaria

The specimens in herbaria help NPS staff and other scientists identify native and nonnative plants in a park. The plants are collected, flattened (in a plant press), dried (often in an oven), and sewn or glued to thick, acid-free sheets with labels (or stored in packets) that document the scientific name, collector, date, location, and other important information. The specimens usually include samples of the different parts of each plant: stems, leaves, flowers, fruits, and maybe even roots. Properly cared for in museum collections, these specimens can survive for hundreds of years.

Each specimen provides proof that a particular species was growing at a particular place at specific point in time. They help scientists describe new plant species, confirm identifications, and study how different species are related. In addition, they document

- where plants grow (and as part of which plant communities);

- when they flower and fruit;

- changes over time to population, location, and other distribution factors;

- potential impacts to rare, threatened, and endangered species;

- overall biodiversity;

- effects of habitat destruction and climate change; and

- the history of plant collecting in a given area.

Hundreds of national parks preserve over 3.5 million plants, conifers, ferns, mosses, liverworts, algae, lichens, and fungi in their museum collections. The oldest specimens in Yellowstone National Park’s herbarium dates to 1899. Many other parks have collections dating from the 1910s and 1920s. Specimens collected in areas before parks were created in that location also exist in other university and museum collections. Many of these collections have been photographed or scanned, and specimens can be viewed in online databases managed by the NPS, universities, or states that bring together knowledge of plant species at regional, state, national, and global levels.

Sources:

Baker, H.G. (1958). Origin of the Vasculum. Proceedings of the Botanical Society of the British Isles. 3: 41–43.

Burns, Ned J. (1941). Field Manual for Museums. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA-00658).

Lewis, Ralph H. (1993). Museum Curatorship in the National Park Service 1904-1982. National Park Service Curatorial Services Division, Washington, DC.

National Park Service. (1939). Miscellaneous Products Available to National Parks and Monuments from the Western Museum Laboratories (Revised Edition). NPS Western Museum Laboratories, Berkeley, California. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645).

Young, Heather. (2024). NPS herbarium specimen statistics from the NPS National Catalog as of May 2, 2024. Pers. comm. with Nancy Russell.