Last updated: February 23, 2021

Article

A True Team Effort: The Fort Donelson Campaign

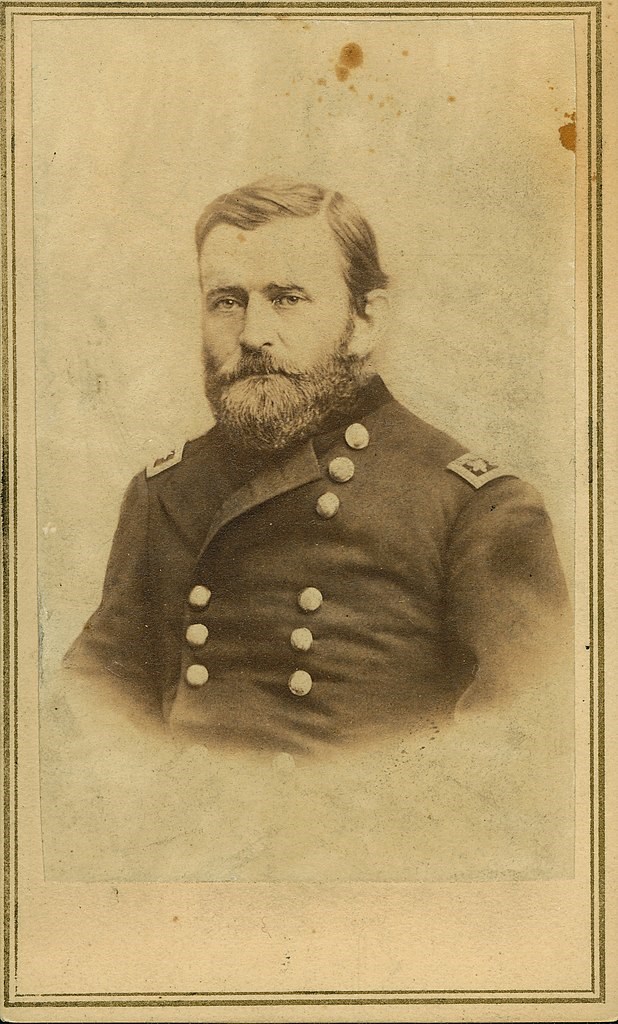

Wikimedia Commons

Work is much better when you have good co-workers that don’t cause you headaches. During the Civil War, General Ulysses S. Grant had his share of conflicts with officers who were hard to work with. Generals John McClernand and Henry Halleck both accused Grant of drunkenness during the war, but Halleck was a particular thorn in Grant’s side during the campaign to take Forts Henry and Donelson. Fort Henry sat on the Tennessee River just below the Kentucky-Tennessee border, while Fort Donelson sat on the Cumberland River below the same border. The two forts blocked the U.S. army from penetrating into the heart of the South through central Tennessee and northern Alabama. Taking control of the forts would be a major accomplishment for the Union forces, and General Grant recognized the situation as a great opportunity to damage the Confederacy.

General C.F. Smith patrolled the Tennessee River near Ft. Henry in early 1862. He advised Grant that the fort could be taken without too much trouble. Grant wasted no time contacting Halleck, who was Grant’s superior and head of the Department of the Missouri, which was headquartered in St. Louis. Grant was eager to arrange a meeting in St. Louis to discuss a strategic advance on Ft. Henry, but Halleck initially chose not to meet with Grant. Being the tenacious person that he was, Grant refused to quit. He continued to request a meeting with Halleck until he finally relented. The meeting, however, did not go well. Halleck abruptly cut Grant off before he could fully explain his plan to take Ft. Henry, forcing Grant to return to his headquarters in Cairo, Illinois, without a tangible plan. Grant felt dejected after the meeting with Halleck, but found a friendly co-worker in Admiral Andrew Foote of the U.S. Navy. Grant explained what he believed needed to be done to take Ft. Henry, and Foote was receptive to the idea. Foote then contacted Halleck to convince the stubborn general how important it would be to take the fort on the Tennessee. Foote was an influential voice and was already in command of a flotilla of ironclad gunboats built by engineer James B. Eads of St. Louis. A combined effort between the Army and Navy could take Ft. Henry and open the Tennessee River all the way into Alabama. General Halleck eventually received intelligence that the Confederates were sending troops to western Kentucky. Even though the intelligence was inaccurate, Halleck chose to authorize Grant and Foote to attack Ft. Henry.

Grant and Foote made their approach towards the Confederates garrisoning Ft. Henry in early February 1862. The fort was commanded by General Lloyd Tilghman who had nearly three thousand men and a few batteries to protect the Tennessee River. The location of the fort had been poorly chosen. It sat at the same level as the river and was partially flooded, making it easy for Foote’s gunboats to fire directly into the garrison. Tilghman realized that Grant was coming overland towards his position while Foote approached with his gunboats. Tilghman did not want the fort to be cut off or forced to surrender his men. He decided to send his infantrymen to Fort Donelson twelve miles away on the Cumberland River. This fort would provide stronger ground for his batteries to confront Foote and Grant. Tilghman hoped to slow the Unionists down just enough for the soldiers to escape to Ft. Donelson. Foote moved his ironclads slowly towards Ft. Henry as Grant tried to make his way through the muddy roads near the fort. Foote began to fire on the garrison when his flotilla was a little less than a mile from the fort. Tilghman ordered his cannoneers to reply with their heavy artillery. The firing greatly intensified when Foote maneuvered to within 600 yards of the fort. The USS Essex took a direct hit in its boiler and was knocked out of the fight. Despite losing the Essex, Foote’s sailors were able to destroy most of Tilghman’s cannon, forcing him to raise the flag of surrender. Tilghman and his artillerists became prisoners-of-war. Tilghman was eventually exchanged in a prisoner swap and later killed at the Battle of Champion Hill during the Vicksburg Campaign in 1863. In any case, General Grant arrived at Ft. Henry within an hour after the surrender took control of the fort. The cooperation between the Army and Navy had led to a successful victory for the Unionists.

Wikipedia

With Ft. Henry taken, Grant and Foote could now place their focus on Ft. Donelson on the Cumberland River. The Unionists would try to open the Cumberland up all the way to Nashville. Grant pursued the Confederates across the land between the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers while Foote took his ironclads back down the Tennessee into the Ohio River before turning up the Cumberland. Grant and Foote tried to combine their forces together once again to capture Ft. Donelson just as they had done to take Ft. Henry. Ft. Donelson, however, would not be as easy to take. The fort sat on land high above the river, giving the Confederates an advantage when Foote approached with his ironclads.

One of the main weaknesses of James B. Eads’ ironclads was the fact that the cannon on the gunboats could not be elevated very high. When Foote began his attack on Ft. Donleson, he struggled to fire his rounds into the Confederate stronghold because it was too far above the river for the rounds to find their intended target. The ironclads took an awful beating during the battle. Foote was injured, later dying of his wounds. Several gunboats that attacked on February 14, 1862 were disabled and taken out of the fight, prompting Grant to have his men dig in around Ft. Donelson. Grant waited until the gunboats could be fully repaired before attacking the Confederates inside Ft. Donelson.

While Grant met with Foote to discuss their next move after the naval engagement, the loud cacophony of battle sounds rang across the landscape. The Confederates were making a move of their own to break out of Ft. Donelson and head towards the direction of Nashville. The Confederates inflicted heavy casualties on the Union right wing commanded by Generals McClernand and Lew Wallace. The Confederates were on their way to successfully breaking out of the fort, but for reasons that remain unclear today Confederate General Gideon Pillow ordered his troops back into Ft. Donelson. Grant wasted little time before ordering a counterattack, which shut the Confederates inside their fort. Once it was evident that the fort would have to be surrendered, most of the Confederate high command escaped from Ft. Donelson, leaving Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner to negotiate the surrender. Grant told Buckner that he would only accept “unconditional surrender.” Buckner did not like the terms, but he knew that he and his army could not break out. Buckner would have to accept Grant’s demands. Ft. Donelson was surrendered on February 16, 1862. Grant had played an enormous role in one of the first major victories for the U.S. military during the American Civil War. The heart of the Confederacy was now open to attack through both the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers.

Anderson, Bern. By Sea and by River: The Naval History of the Civil War. New York: Knopf,1962.

Grant, Ulysses S. Memoirs and Selected Letters. New York: The Library of America, 1990.

Silkenat, David. Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Smith, Timothy B. Grant Invades Tennessee: The 1862 Battles of Forts Henry and Donelson. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016.