Last updated: April 4, 2025

Article

Across the Border to Goat Haunt

Despite the ghostly-sounding name, “Goat Haunt” refers to a place where goats live.

In Glacier National Park, Goat Haunt is a remote outpost where we celebrate our ongoing friendship with Canada. The infrastructure at Goat Haunt seen today was built in the 1960s as part of the famous Mission 66 program. In 2024, a new series of exhibits was installed in the Goat Haunt Peace Pavillion. This article summarizes the contents of those exhibits.

The 49th Parallel

In 1845, the border between the United States and British North America ended at the Rocky Mountains (Canada didn’t exist yet). The land west of the Rockies was contested, as both countries claimed it for their own.The largest territory claim made by the U.S. drew the border at latitude 54°40’, reaching all the way to (then Russian-owned) Alaska. Britain and the Hudson Bay Company claimed as far south as present-day Oregon.

Ultimately, the two nations compromised, and agreed on the 49th parallel in 1846. After drawing the border on the map, they tasked surveyors with locating it—sending one team from each country to etch it onto the landscape.

Cutting the Boundary

Crews used the night sky to locate the border—measuring the angle of known stars to determine their latitude and marking the 49th parallel with stone monuments.The hardest step was clearing the 40-foot boundary swath. To trace the border’s straight line, surveyors waded through grasslands, chopped through forests, and climbed over mountains.

The work was dangerous; along the 410-mile journey, falling trees led to several casualties. Progress was slowed further by raging rivers, clouds of mosquitoes, encounters with wildlife, and even the onset of the American Civil War.

Yet, after just four years of work, they were finished. In 1861, the world’s longest international border was complete. The swath still divides Glacier and Waterton Lakes today.

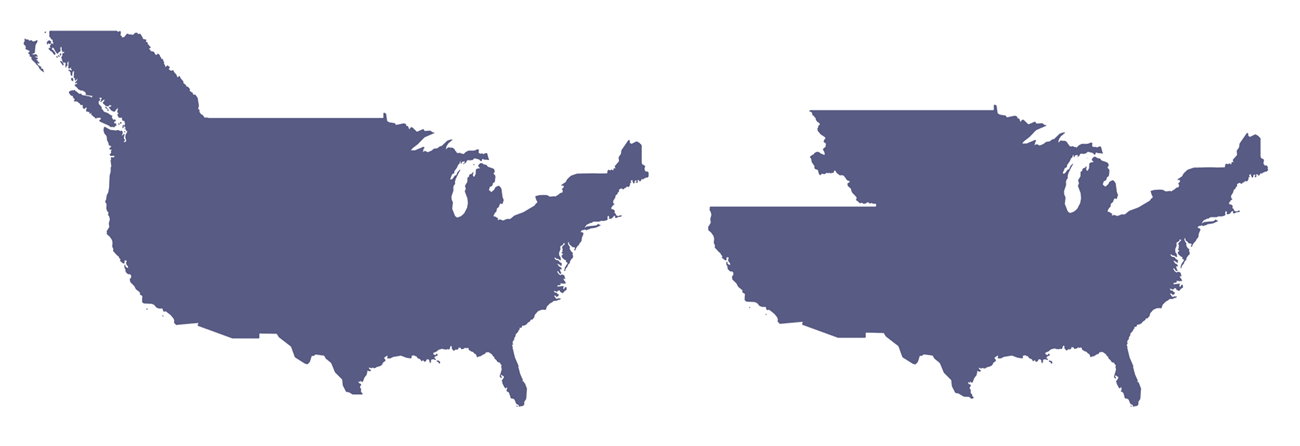

Competing border proposals: on the left is the largest U.S. territory claim and on the right is the largest British claim.

People Living Across the Border

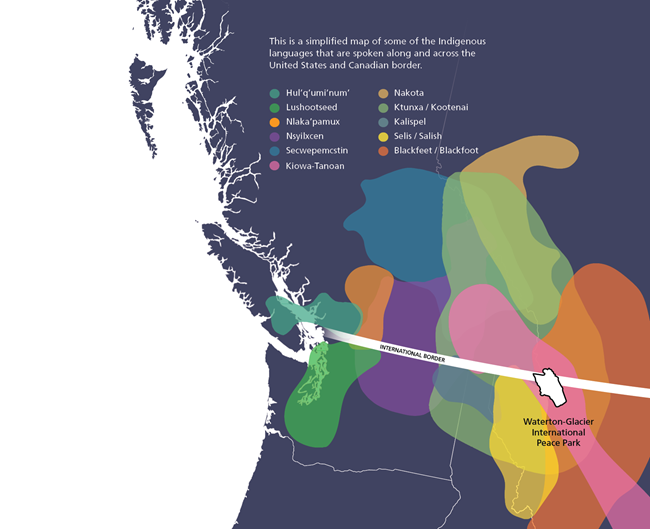

Rigidly defined boundaries between nation-states are a relatively recent development compared to the millennia that Indigenous people have been living here. The creation of the border between the United States and Canada in the 1860s divided many Native American Tribes and families, including those in and around Glacier National Park.After the border was established, Indigenous people continued to practice their seasonal travels back and forth across the border, keeping ties to this place which holds meaning and story. This contrasts with the strict border definitions used by the United States and Canadian governments.

Today Native American Tribes and families still maintain relationships and cultural ties, despite the border.

You can expore these Indigenous Language maps yourself here:https://native-land.ca/

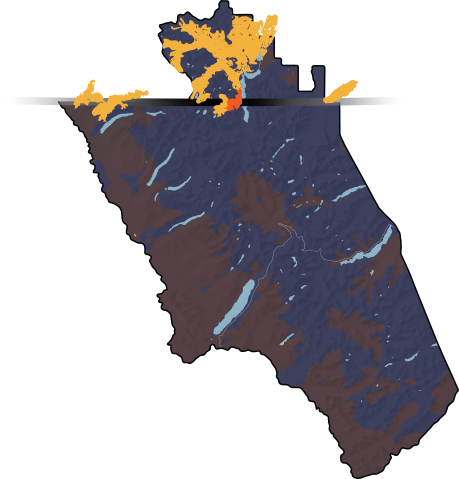

Burning Across the Border

If a fire starts on your neighbor’s land, would you help put it out? Prevailing winds in this area blow from the southwest. This means that fires in the northern reaches of Glacier often cross the international border into Waterton Lakes National Park.One such fire was the 1935 Boundary Fire that started in Glacier, then spread into Waterton. Over 250 Americans, including Civilian Conservation Corps crews, and 80 Canadians responded to the fire, which eventually burned over 2,000 acres. As a Peace Park, both Glacier and Waterton support each other’s fire management efforts on both sides of the border.

Flying Over Borders

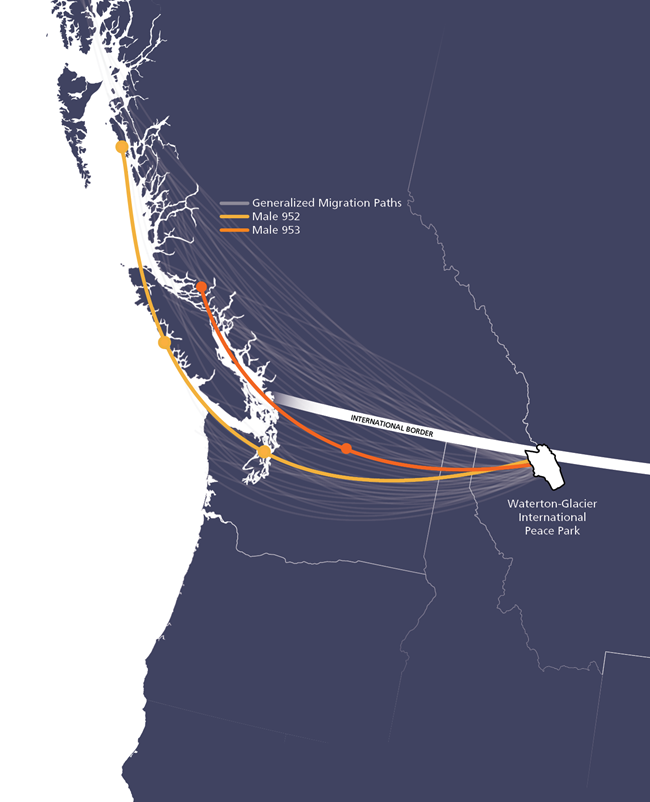

Migrating animals need several habitats to survive. Harlequin ducks, for example, spend spring and summer in Glacier’s whitewater streams and rivers. In the fall, they migrate west to the ocean waters along the Canadian coast, where they spend the winter. Harlequins need healthy habitat at each of these places.Complicating conservation efforts, their habitats can span international borders, both season to season, and day to day. In this area, harlequins often spend summer nights resting on a lake in Canada and the days on a river in the United States. Protecting harlequins requires thinking beyond their breeding season and across political boundaries.

Harlequin ducks are named for the way males (right) resemble jester-like characters. Female harlequins (left) are mostly brown with a white spot on their heads.

The World's First Peace Park

The year was 1932 and the world was wrapped in the stifling blanket of depression, famine, and anguish left by the Great War.

Despite these difficult times, a group of optimistic citizens along the international boundary between Alberta and Montana found a way to shine a beacon of light into this darkness. Members of Rotary Clubs, both north and south of the 49th parallel, found an inspiring way to celebrate the friendship and cooperation between Canada and the United States.

The first annual goodwill meeting between the Rotarians of Alberta and Montana took place at the Prince of Wales Hotel, on Saturday, July 4, 1931. There, a resolution to establish an International Peace Park was approved.

In 1932, negotiations with local government representatives in both countries led to the joining of the two national parks when the U.S. Congress and the Canadian Parliament created legislation establishing “Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park.”

Over the years, the first Peace Park matured into an example of successful cooperative management of a larger ecosystem shared by two countries. Today, each park strives to work together to celebrate and protect the significant variety of natural and cultural features found in this part of the Rocky Mountains.

True to its roots as a beacon of hope, the Peace Park continues to inspire contemplation of the importance of respect and cooperation between nations.

More Information

The background photograph is from the Library of Congress: Indian encampment, Tobacco Plains, Kootenay [i.e., Kootenai] River - fish trap in the foreground, 1861 - color film copy transparency | Library of Congress (loc.gov)

Lozar, Patrick. “‘They Do Not, Therefor, Regard the Boundary Line as Separating Them’: The Ktunaxa Nation and the Enforcement of the U.S.-Canadian Border, 1887.” Montana Magazine of Western History 54, no. 4 (2020): 54–72. https://www.academia.edu/45017128/_They_do_not_therefor_regard_the_boundary_line_as_separating_them_The_Ktunaxa_Nation_and_the_Enforcement_of_the_U_S_Canadian_Border_1887.

Pp. 55. “The international boundary cut through the heart of Ktunaxa territory, but for decades Ktunaxa people moved freely across the border in accordance with their traditional seasonal rounds and social customs.”

Pp. 62. “Canada and the United States perceived the free movement of Indigenous people across the boundary as a threat to their authority and, consequently, intensified their presence at the line in 1887 to prevent Ktunaxa cross-border cooperation.”

Pp. 72. “Canadian and U.S. histories have buried Indigenous connections across the forty-ninth parallel; for the Ktunaxa Nation, however, the relationships and cultural ties that bind the people together endure in spite of the border.”

Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, S. Ligocki, O. Robinson, W. Hochachka, L. Jaromczyk, A. Rodewald, C. Wood, I. Davies, A. Spencer. 2022. eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2021; Released: 2022. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://science.ebird.org/status-and-trends/species/harduc/abundance-map

Headwaters Podcast. Glacier National Park. (2020). “Goat Haunt” https://www.nps.gov/podcasts/headwaters.htm?season=0&reinit=false&hiderightrail=true&maxrows=10&sortby=date%2Ddesc&startrow=21

Harlequin Ducks Resource Brief (U.S. National Park Service) 2018 https://www.nps.gov/articles/harlequin-ducks.htm

The Cornell Lab “Harlequin Duck” https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Harlequin_Duck/overview