Part of a series of articles titled Superintendent Articles about Brown v. Board of Education NHP.

Article

The Continuing Debate over the Meaning of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision

Back row, left to right: Associate Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh, and Kentanji Brown Jackson.

Credit: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

On June 29, 2023, the US Supreme Court decided the cases Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, et al. In the majority and dissenting opinions, several justices continued the debate over the meaning of the Brown v. Board of Education decision issued by the Supreme Court in 1954. The full text of the 237-page decision and opinions cited in this article may be found in pdf format at the Supreme Court’s website . Note: Each justice’s opinion is paginated separately from the others.

Majority Opinion: Brown v. Board of Education “Invalidated All Manner of Race-Based State Action”

As Chief Justice John Roberts stated, “In these cases we consider whether the admissions systems used by Harvard College and the University of North Carolina, two of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the United States, are lawful under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” (p. 1).

In section III of the majority’s analysis, the court argued (pp. 11-13):

After Plessy, “American courts . . . labored with the doctrine [of separate but equal] for over half a century.” Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 491 (1954). Some cases in this period attempted to curtail the perniciousness of the doctrine by emphasizing that it required States to provide black students educational opportunities equal to— even if formally separate from—those enjoyed by white students. See, e.g., Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, 349–350 (1938) (“The admissibility of laws separating the races in the enjoyment of privileges afforded by the State rests wholly upon the equality of the privileges which the laws give to the separated groups . . . .”). But the inherent folly of that approach—of trying to derive equality from inequality—soon became apparent. As the Court subsequently recognized, even racial distinctions that were argued to have no palpable effect worked to subordinate the afflicted students. See, e.g., McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Ed., 339 U. S. 637, 640–642 (1950) (“It is said that the separations imposed by the State in this case are in form merely nominal. . . . But they signify that the State . . . sets [petitioner] apart from the other students.”). By 1950, the inevitable truth of the Fourteenth Amendment had thus begun to reemerge: Separate cannot be equal.

The culmination of this approach came finally in Brown v. Board of Education. In that seminal decision, we overturned Plessy for good and set firmly on the path of invalidating all de jure racial discrimination by the States and Federal Government. 347 U. S., at 494–495. Brown concerned the permissibility of racial segregation in public schools. The school district maintained that such segregation was lawful because the schools provided to black students and white students were of roughly the same quality. But we held such segregation impermissible “even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal.” Id., at 493 (emphasis added). The mere act of separating “children . . . because of their race,” we explained, itself “generate[d] a feeling of inferiority.” Id., at 494.

The conclusion reached by the Brown Court was thus unmistakably clear: the right to a public education “must be made available to all on equal terms.” Id., at 493. As the plaintiffs had argued, “no State has any authority under the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to use race as a factor in affording educational opportunities among its citizens.” Tr. of Oral Arg. in Brown I, O. T. 1952, No. 8, p. 7 (Robert L. Carter, Dec. 9, 1952); see also Supp. Brief for Appellants on Reargument in Nos. 1, 2, and 4, and for Respondents in No. 10, in Brown v. Board of Education, O. T. 1953, p. 65 (“That the Constitution is color blind is our dedicated belief.”); post, at 39, n. 7 (THOMAS, J., concurring). The Court reiterated that rule just one year later, holding that “full compliance” with Brown required schools to admit students “on a racially nondiscriminatory basis.” Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300–301 (1955). The time for making distinctions based on race had passed. Brown, the Court observed, “declar[ed] the fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional.” Id., at 298.

So too in other areas of life. Immediately after Brown, we began routinely affirming lower court decisions that invalidated all manner of race-based state action. . . .

After many pages of historical and legal analysis, the majority opinion takes on the dissenting justices and returns to the Brown decision (pp. 38-39), and even goes back to the Plessy decision that Brown overturned:

Most troubling of all is what the dissent must make these omissions to defend: a judiciary that picks winners and losers based on the color of their skin. While the dissent would certainly not permit university programs that discriminated against black and Latino applicants, it is perfectly willing to let the programs here continue. In its view, this Court is supposed to tell state actors when they have picked the right races to benefit. Separate but equal is “inherently unequal,” said Brown. 347 U.S., at 495 (emphasis added). It depends, says the dissent.

That is a remarkable view of the judicial role—remarkably wrong. Lost in the false pretense of judicial humility that the dissent espouses is a claim to power so radical, so destructive, that it required a Second Founding to undo. “Justice Harlan knew better,” one of the dissents decrees. Post, at 5 (opinion of JACKSON, J.). Indeed he did:

“[I]n view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” Plessy, 163 U. S., at 559 (Harlan, J., dissenting).

In prohibiting race-based admissions factors at the university level, the court concluded that:

In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race. Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice. (p. 40)

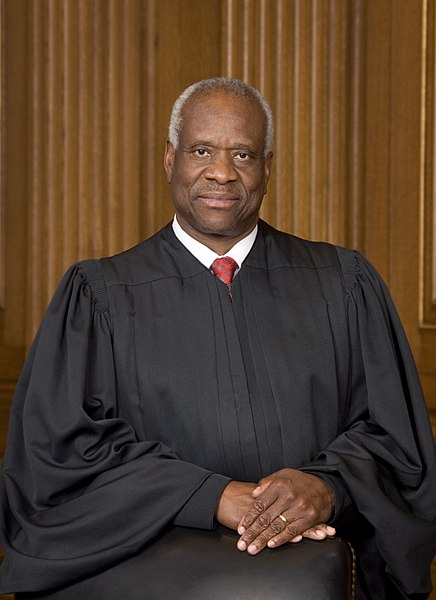

Justice Thomas Concurs with the Majority: “The Alleged Educational Benefits of Diversity Cannot Justify Racial Discrimination Today”

Justice Clarence Thomas concurred with the majority and issued his own opinion, which also cites the Brown decision as he elaborated on his interpretation of race and the intent of the Fourteenth Amendment:

I do not contend that all of the individuals who put forth and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment universally believed this to be true [that all citizens of the U.S., regardless of skin color, are equal before the law]. Some Members of the proposing Congress, for example, opposed the Amendment. And, the historical record—particularly with respect to the debates on ratification in the States—is sparse. Nonetheless, substantial evidence suggests that the Fourteenth Amendment was passed to “establis[h] the broad constitutional principle of full and complete equality of all persons under the law,” forbidding “all legal distinctions based on race or color.” Supp. Brief for United States on Reargument in Brown v. Board of Education, O. T. 1953, No. 1 etc., p. 115 (U. S. Brown Reargument Brief ). (p. 3)

Later, Thomas returns to Brown in arguing that what some would call reverse discrimination or affirmative action—giving one group preference to address inequalities of the past—is unconstitutional.

For this reason, “just as the alleged educational benefits of segregation were insufficient to justify racial discrimination [in the 1950s], see Brown v. Board of Education, the alleged educational benefits of diversity cannot justify racial discrimination today.” Fisher I, 570 U.S., at 320 (THOMAS, J., concurring) (citation omitted). (p. 26)

Several pages later, Thomas refers to Brown again. In contrast to the “separate but equal” doctrine the court affirmed in 1896 in the Plessy decision:

This Court rightly reversed course in Brown v. Board of Education. The Brown appellants—those challenging segregated schools—embraced the equality principle, arguing that “[a] racial criterion is a constitutional irrelevance, and is not saved from condemnation even though dictated by a sincere desire to avoid the possibility of violence or race friction.” Appellants in Brown v. Board of Education, O. T. 1952, No. 1, p. 7 (citation omitted).6 Embracing that view, the Court held that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place” and “[s]eparate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Brown, 347 U. S., at 493, 495. Importantly, in reaching this conclusion, Brown did not rely on the particular qualities of the Kansas schools. The mere separation of students on the basis of race—the “segregation complained of,” id., at 495 (emphasis added)—constituted a constitutional injury. See ante, at 12 (“Separate cannot be equal”).

Just a few years later, the Court’s application of Brown made explicit what was already forcefully implied: “[O]ur decisions have foreclosed any possible contention that . . . a statute or regulation” fostering segregation in public facilities “may stand consistently with the Fourteenth Amendment.” Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350, 353 (1962) (per curiam); cf. A. Blaustein & C. Ferguson, Desegregation and the Law: The Meaning and Effect of the School Segregation Cases 145 (rev. 2d ed. 1962) (arguing that the Court in Brown had “adopt[ed] a constitutional standard” declaring “that all classification by race is unconstitutional per se”). . . .

The Court today reaffirms the rule, stating that, following Brown, “[t]he time for making distinctions based on race had passed.” Ante, at 13. “What was wrong” when the Court decided Brown “in 1954 cannot be right today.” Parents Involved, 551 U. S., at 778 (THOMAS, J., concurring). Rather, we must adhere to the promise of equality under the law declared by the Declaration of Independence and codified by the Fourteenth Amendment. (pp. 36-37)

[Footnote 6 from above: Briefing in a case consolidated with Brown stated the colorblind position forthrightly: Classifications “[b]ased [s]olely on [r]ace or [c]olor” “can never be” constitutional. Juris. Statement in Briggs v. Elliott, O. T. 1951, No. 273, pp. 20–21, 25, 29; see also Juris. Statement in Davis v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward Cty., O. T. 1952, No. 191, p. 8 (“Indeed, we take the unqualified position that the Fourteenth Amendment has totally stripped the state of power to make race and color the basis for governmental action. . . . For this reason alone, we submit, the state separate school laws in this case must fall”).]

In the next section of his opinion, Thomas returns to the Virginia case from Prince Edward County decided as part of the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Here, he asserts that affirmative action in these 2023 cases is a form of racial discrimination for the good of black students.

Arguments for the benefits of race-based solutions have proved pernicious in segregationist circles. Segregated universities once argued that race-based discrimination was needed “to preserve harmony and peace and at the same time furnish equal education to both groups.” Brief for Respondents in Sweatt v. Painter, O. T. 1949, No. 44, p. 94; see also id., at 79 (“‘[T]he mores of racial relationships are such as to rule out, for the present at least, any possibility of admitting white persons and Negroes to the same institutions’ ”). And, parties consistently attempted to convince the Court that the time was not right to disrupt segregationist systems. See Brief for Appellees in McLaurin v. O lahoma State Regents for Higher Ed., O. T. 1949, No. 34, p. 12 (claiming that a holding rejecting separate but equal would “necessarily result . . . [i]n the abandoning of many of the state’s existing educational establishments” and the “crowding of other such establishments”); Brief for State of Kansas on Reargument in Brown v. Board of Education, O. T. 1953, No. 1, p. 56 (“We grant that segregation may not be the ethical or political ideal. At the same time we recognize that practical considerations may prevent realization of the ideal”); Tr. of Oral Arg. in Davis v. School Bd. of Prince Edward Cty., O. T. 1954, No. 3, p. 208 (“We are up against the proposition: What does the Negro profit if he procures an immediate detailed decree from this Court now and then impairs or mars or destroys the public school system in Prince Edward County”). Litigants have even gone so far as to offer straight-faced arguments that segregation has practical benefits. Brief for Respondents in Sweatt v. Painter, at 77–78 (requesting deference to a state law, observing that “ ‘the necessity for such separation [of the races] still exists in the interest of public welfare, safety, harmony, health, and recreation . . .’ ” and remarking on the reasonableness of the position); Brief for Appellees in Davis v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward Cty., O. T. 1952, No. 3, p. 17 (“Virginia has established segregation in certain fields as a part of her public policy to prevent violence and reduce resentment. The result, in the view of an overwhelming Virginia majority, has been to improve the relationship between the different races”); id., at 25 (“If segregation be stricken down, the general welfare will be definitely harmed . . . there would be more friction developed” (internal quotation marks omitted)). In fact, slaveholders once “argued that slavery was a ‘positive good’ that civilized blacks and elevated them in every dimension of life,” and “segregationists similarly asserted that segregation was not only benign, but good for black students.” Fisher I, 570 U. S., at 328–329 (THOMAS, J., concurring).

“Indeed, if our history has taught us anything, it has taught us to beware of elites bearing racial theories.” Parents Involved, 551 U. S., at 780–781 (THOMAS, J., concur- ring). We cannot now blink reality to pretend, as the dissents urge, that affirmative action should be legally permissible merely because the experts assure us that it is “good” for black students. Though I do not doubt the sincerity of my dissenting colleagues’ beliefs, experts and elites have been wrong before—and they may prove to be wrong again. In part for this reason, the Fourteenth Amendment outlaws government-sanctioned racial discrimination of all types. The stakes are simply too high to gamble. Then, as now, the views that motivated Dred Scott and Plessy have not been confined to the past, and we must remain ever vigilant against all forms of racial discrimination. (pp.37-39)

Before taking on Justice Jackson’s dissent [see below], Justice Thomas concludes that:

The solution to our Nation’s racial problems thus cannot come from policies grounded in affirmative action or some other conception of equity. Racialism simply cannot be un- done by different or more racialism. Instead, the solution announced in the second founding is incorporated in our Constitution: that we are all equal, and should be treated equally before the law without regard to our race. Only that promise can allow us to look past our differing skin colors and identities and see each other for what we truly are: individuals with unique thoughts, perspectives, and goals, but with equal dignity and equal rights under the law. (pp. 48-49)

Justice Kavanaugh Concurs: Brown v. Board of Education “Authorized Race-Based Student Assignments for Several Decades—but Not Indefinitely into the Future”

In an eight-page concurring opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh provides more detail to the legal precedents that he believes limit the states’ ability to use race in educational policy. Relying on the court’s decision in Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003, among others, Kavanaugh concludes, the “Court has long held that racial classifications by the government, including race-based affirmative action programs, are subject to strict judicial scrutiny. Under strict scrutiny, racial classifications are constitutionally prohibited unless they are narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest.” “Importantly,” he continues, “even if a racial classification is otherwise narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest, a ‘deviation from the norm of equal treatment of all racial and ethnic groups’ must be ‘a temporary matter’—or stated otherwise, must be ‘limited in time.’” (p. 2)

Later, Kavanaugh returns to the Brown decision as the first example of the court’s consistent limitation on the time allowed for “race-based student assignments” at the K-12 level:

For example, in the elementary and secondary school context after Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the Court authorized race-based student assignments for several decades—but not indefinitely into the future. See, e.g., Board of Ed. of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, 498 U. S. 237, 247–248 (1991); Pasadena City Bd. of Ed. v. Spangler, 427 U. S. 424, 433–434, 436 (1976); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U. S. 1, 31–32 (1971); cf. McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U. S. 39, 41 (1971). In those decisions, this Court ruled that the race-based “injunctions entered in school desegregation cases” could not “operate in perpetuity.” Dowell, 498 U. S., at 248. (p. 6)

Justice Sotomayor’s Dissent: Brown Created a “Vision of a Nation with More Inclusive Schools” and the “Court’s Recharacterization of Brown Is Nothing but Revisionist History and an Affront to the Legendary Life of Justice Marshall”

In writing the main dissenting opinion for herself and Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, Justice Sonia Sotomayor begins with the decision in Brown v. Board of Education:

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment enshrines a guarantee of racial equality. The Court long ago concluded that this guarantee can be enforced through race-conscious means in a society that is not, and has never been, colorblind. In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the Court recognized the constitutional necessity of racially integrated schools in light of the harm inflicted by segregation and the “importance of education to our democratic society.” Id., at 492–495. For 45 years, the Court extended Brown’s transformative legacy to the context of higher education, allowing colleges and universities to consider race in a limited way and for the limited purpose of promoting the important benefits of racial diversity. This limited use of race has helped equalize educational opportunities for all students of every race and background and has improved racial diversity on college campuses. Although progress has been slow and imperfect, race-conscious college admissions policies have advanced the Constitution’s guarantee of equality and have promoted Brown’s vision of a Nation with more inclusive schools.

Today, this Court stands in the way and rolls back decades of precedent and momentous progress. It holds that race can no longer be used in a limited way in college admissions to achieve such critical benefits. In so holding, the Court cements a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter. The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society. Because the Court’s opinion is not grounded in law or fact and contravenes the vision of equality embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment, I dissent. (pp. 1-2)

Later, Sotomayor returns to the debate about the relationship between the Plessy and Brown decisions, and whether in deciding that segregated education was unconstitutional the court also said that race could not play a role is remedying past discrimination against African Americans.

It was not until half a century later, in Brown, that the Court honored the guarantee of equality in the Equal Protection Clause and Justice Harlan’s vision of a Constitution that “neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” Ibid. Considering the “effect[s] of segregation” and the role of education “in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation,” Brown overruled Plessy. 347 U. S., at 492–495. The Brown Court held that “[s]eparate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” and that such racial segregation deprives Black students “of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Id., at 494–495. The Court thus ordered segregated schools to transition to a racially integrated system of public education “with all deliberate speed,” “ordering the immediate admission of [Black children] to schools previously attended only by white children.” Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 301 (1955).

Brown was a race-conscious decision that emphasized the importance of education in our society. Central to the Court’s holding was the recognition that, as Justice Harlan emphasized in Plessy, segregation perpetuates a caste system wherein Black children receive inferior educational opportunities “solely because of their race,” denoting “inferiority as to their status in the community.” 347 U. S., at 494, and n. 10. Moreover, because education is “the very foundation of good citizenship,” segregation in public education harms “our democratic society” more broadly as well. Id., at 493. In light of the harmful effects of entrenched racial subordination on racial minorities and American democracy, Brown recognized the constitutional necessity of a racially integrated system of schools where education is “available to all on equal terms.” Ibid. (p. 11)

The desegregation cases that followed Brown confirm that the ultimate goal of that seminal decision was to achieve a system of integrated schools that ensured racial equality of opportunity, not to impose a formalistic rule of race-blindness. . . . (p. 12)

In so holding, this Court’s post-Brown decisions rejected arguments advanced by opponents of integration suggesting that “restor[ing] race as a criterion in the operation of the public schools” was at odds with “the Brown decisions.” Brief for Respondents in Green v. School Bd. of New Kent Cty., O. T. 1967, No. 695, p. 6 (Green Brief). Those opponents argued that Brown only required the admission of Black students “to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis.” Id., at 11 (emphasis deleted). Relying on Justice Harlan’s dissent in Plessy, they argued that the use of race “is improper” because the “‘Constitution is colorblind.’” Green Brief 6, n. 6 (quoting Plessy, 163 U. S., at 559 (Harlan, J., dissenting)). They also incorrectly claimed that their views aligned with those of the Brown litigators, arguing that the Brown plaintiffs “understood” that Brown’s “mandate” was colorblindness. Green Brief 17. This Court rejected that characterization of “the thrust of Brown.” Green, 391 U. S., at 437. It made clear that indifference to race “is not an end in itself” under that watershed decision. Id., at 440. The ultimate goal is racial equality of opportunity.

Those rejected arguments mirror the Court’s opinion today. The Court claims that Brown requires that students be admitted “‘on a racially nondiscriminatory basis.’” Ante, at 13. It distorts the dissent in Plessy to advance a colorblindness theory. Ante, at 38–39; see also ante, at 22 (GORSUCH, J., concurring) (“[T]oday’s decision wakes the echoes of Justice John Marshall Harlan [in Plessy]”); ante, at 3 (THOMAS, J., concurring) (same). The Court also invokes the Brown litigators, relying on what the Brown “plaintiffs had argued.” Ante, at 12; ante, at 35–36, 39, n. 7 (opinion of THOMAS, J.).

If there was a Member of this Court who understood the Brown litigation, it was Justice Thurgood Marshall, who “led the litigation campaign” to dismantle segregation as a civil rights lawyer and “rejected the hollow, race-ignorant conception of equal protection” endorsed by the Court’s ruling today. Brief for NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., et al. as Amici Curiae 9. Justice Marshall joined the Bakke plurality and “applaud[ed] the judgment of the Court that a university may consider race in its admissions process.” 438 U. S., at 400. In fact, Justice Marshall’s view was that Bakke’s holding should have been even more protective of race-conscious college admissions programs in light of the remedial purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment and the legacy of racial inequality in our society. See id., at 396–402 (arguing that “a class-based remedy” should be constitutionally permissible in light of the hundreds of “years of class-based discrimination against [Black Americans]”). The Court’s recharacterization of Brown is nothing but revisionist history and an affront to the legendary life of Justice Marshall, a great jurist who was a champion of true equal opportunity, not rhetorical flourishes about colorblindness. (pp.13-14)

Sotomayor summarizes:

In short, for more than four decades, it has been this Court’s settled law that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment authorizes a limited use of race in college admissions in service of the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body. From Brown to Fisher, this Court’s cases have sought to equalize educational opportunity in a society structured by racial segregation and to advance the Fourteenth Amendment’s vision of an America where racially integrated schools guarantee students of all races the equal protection of the laws.

Today, the Court concludes that indifference to race is the only constitutionally permissible means to achieve racial equality in college admissions. That interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment is not only contrary to precedent and the entire teachings of our history, see supra, at 2–17, but is also grounded in the illusion that racial inequality was a problem of a different generation. Entrenched racial inequality remains a reality today. (p. 17)

Much later in her dissent, Sotomayor again returns to the meaning of the Brown decision for American educational equity:

Nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment or its history supports the Court’s shocking proposition, which echoes arguments made by opponents of Reconstruction-era laws and this Court’s decision in Brown. Supra, at 2–17. In a society where opportunity is dispensed along racial lines, racial equality cannot be achieved without making room for underrepresented groups that for far too long were denied admission through the force of law, including at Harvard and UNC. Quite the opposite: A racially integrated vision of society, in which institutions reflect all sectors of the American public and where “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners [are] able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” is precisely what the Equal Protection Clause commands. Martin Luther King “I Have a Dream” Speech (Aug. 28, 1963). It is “essential if the dream of one Nation, indivisible, is to be realized.” Grutter, 539 U. S., at 332.34

[Footnote 34:] 34The Court suggests that promoting the Fourteenth Amendment’s vision of equality is a “radical” claim of judicial power and the equivalent of “pick[ing] winners and losers based on the color of their skin.” Ante, at 38. The law sometimes requires consideration of race to achieve racial equality. Just like drawing district lines that comply with the Voting Rights Act may require consideration of race along with other demographic factors, achieving racial diversity in higher education requires consideration of race along with “age, economic status, religious and political persuasion, and a variety of other demographic factors.” Shaw v. Reno, 509 U. S. 630, 646 (1993) (“[R]ace consciousness does not lead inevitably to impermissible race discrimination”). Moreover, in ordering the admission of Black children to all-white schools “with all deliberate speed” in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 301 (1955), this Court did not decide that the Black children should receive an “advantag[e] . . . at the expense of” white children. Ante, at 27. It simply enforced the Equal Protection Clause by leveling the playing field. (p. 46)

Concluding her opinion, Sotomayor again asserts her understanding of the meaning of the Brown decision in 1954:

True equality of educational opportunity in racially diverse schools is an essential component of the fabric of our democratic society. It is an interest of the highest order and a foundational requirement for the promotion of equal protection under the law. Brown recognized that passive race neutrality was inadequate to achieve the constitutional guarantee of racial equality in a Nation where the effects of segregation persist. In a society where race continues to matter, there is no constitutional requirement that institutions attempting to remedy their legacies of racial exclusion must operate with a blindfold.

Today, this Court overrules decades of precedent and imposes a superficial rule of race blindness on the Nation. The devastating impact of this decision cannot be overstated. The majority’s vision of race neutrality will entrench racial segregation in higher education because racial inequality will persist so long as it is ignored. (p. 68-69)

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s Dissent: Let’s “Acknowledge the Well-Documented ‘Intergenerational Transmission of Inequality’ That Still Plagues Our Citizenry”

Justice Jackson concurs with Justices Sotomayor and Kagan in Sotomayor’s dissent. She uses her own dissenting opinion to expand upon the history of “gulf-sized race-based gaps” that “exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens. They have been created in the distant past, but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations.” (p. 1)

Toward the end of her opinion, Jackson condemns the majority’s analysis of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Brown v. Board of Education decision:

The overarching reason the majority gives for becoming an impediment to racial progress—that its own conception of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause leaves it no other option—has a wholly self-referential, two-dimensional flatness. The majority and concurring opinions rehearse this Court’s idealistic vision of racial equality, from Brown forward, with appropriate lament for past indiscretions. See, e.g., ante, at 11. But the race-linked gaps that the law (aided by this Court) previously founded and fostered—which indisputably define our present reality—are strangely absent and do not seem to matter.

With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces “colorblindness for all” by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life. And having so detached itself from this country’s actual past and present experiences, the Court has now been lured into interfering with the crucial work that UNC and other institutions of higher learning are doing to solve America’s real-world problems.

No one benefits from ignorance. Although formal race-linked legal barriers are gone, race still matters to the lived experiences of all Americans in innumerable ways, and today’s ruling makes things worse, not better. The best that can be said of the majority’s perspective is that it proceeds (ostrich-like) from the hope that preventing consideration of race will end racism. But if that is its motivation, the majority proceeds in vain. If the colleges of this country are required to ignore a thing that matters, it will not just go away. It will take longer for racism to leave us. And, ultimately, ignoring race just makes it matter more.

The only way out of this morass—for all of us—is to stare at racial disparity unblinkingly, and then do what evidence and experts tell us is required to level the playing field and march forward together, collectively striving to achieve true equality for all Americans. It is no small irony that the judgment the majority hands down today will forestall the end of race-based disparities in this country, making the colorblind world the majority wistfully touts much more difficult to accomplish. (pp. 24-26

By legislative mandate, Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park exists “to honor the civil rights stories of struggle, perseverance, and activism in the pursuit of education equity.” [Public Law 117-123, section 3]

Compiled by James H. Williams, PhD, Superintendent

Tags

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- supreme court of the united states

- affirmative action

- brown v. the board of education of topeka

- civil rights

- civil rights era

- 1950s

- african american civil rights

- african america history

- african amercan heritage

- landmark supreme court case

- naacp

- supreme court

- brown v. board

- brown v. board of education

- plessy v. ferguson

- 14th amendement

Last updated: August 10, 2023