Part of a series of articles titled What Daddy and Mother did in the War.

Article

What Daddy and Mother did in the War (Part 1)

Robert Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

by Stephanie Johnson Dixon, 2007

Introduction

This project started as a result of watching too much public television. In early October of 2007 PBS ran a series by the documentary filmmaker Ken Burns. This series, “The War,” (or as pronounced by an old witness from Alabama who both looked and sounded like our dear Mammy, “the Waw”) ran for about eight days and chronicled people who actually lived through and fought during World War II. That is not so unusual. We’ve all seen war footage and heard veteran’s commentaries since the end of that war. What made it different was that for the first time we followed the same people throughout the war. Plus, we saw how it affected whole communities and the affects of the war on people’s entire lives.

Watching this series, my husband, Bill, and I had a couple of reactions. (1) This is fascinating stuff; (2) We can do that. What Ken Burns did was the same thing he does in all his films…take archival pictures and footage, get either eyewitness interviews or have people read actual accounts from the times he covering, and drag it out beyond belief. We were inspired.

Fortunately, at the end of each night’s episode there was a sort of a call to action. It seems that with all of the World War II veterans nearly gone, someone finally decided that it was a good idea to get the oral histories of the remaining vets and others who aided in the war effort. The Library of Congress started what became known as The Veterans History Project. Volunteers were needed to find remaining veterans and get their memories on tape. Right up our alley.

So Bill and I started making plans to do this. We decided to start in Marianna, my hometown and resting place of my father, Bob Johnson, a veteran of World War II and with years of service in the Aleutians. We went over one day, looked up the current American Legion Post Commander, Jim Davis, and asked if we could use the Legion Hut to conduct interviews. We picked his brain for possible survivors that we might interview. We put an article in the The Courier-Index explaining what we were up to and asked for interested people to call and set up interview times. We were on our way to becoming documentarians for the Library of Congress.

Somewhere early in this process, it occurred to me that although I thought I had a pretty good understanding of where my own parents fit into the World War II era and what their roles were, there were definite gaps in my knowledge. Neither Mother nor Daddy talked much about those days. When they did, it had to be pried out of them. So I decided that if I was going to participate in this oral history project on other veterans, I would try to piece together my parents’ oral histories, as well.

This is not as easy as it sounds. When parents are gone and neither of them were great record-keepers, one has to rely on one’s own memory. Memory fades, your own as well as others. People, such as aunts, uncles, old friends of your parents have less reliable memories, move away, or die. The whole process was made more difficult because 80% of the Army veteran’s records from 1912 to l960 were destroyed in a 1973 fire of the building in St. Louis that housed all those records.

Try to imagine what kind of grief this fire and that oversight caused. For this small project it meant that there was no central records place to go to in order to track Bob Johnson’s military service. There was no paper record that I could lay my hands on at the time of this writing that made it simple to say “Okay, here I see that he was in Ft. Bliss in l941 starting in January” or “Yes, he did win the Purple Heart for frost-bitten feet.” This would have to be done the hard way.

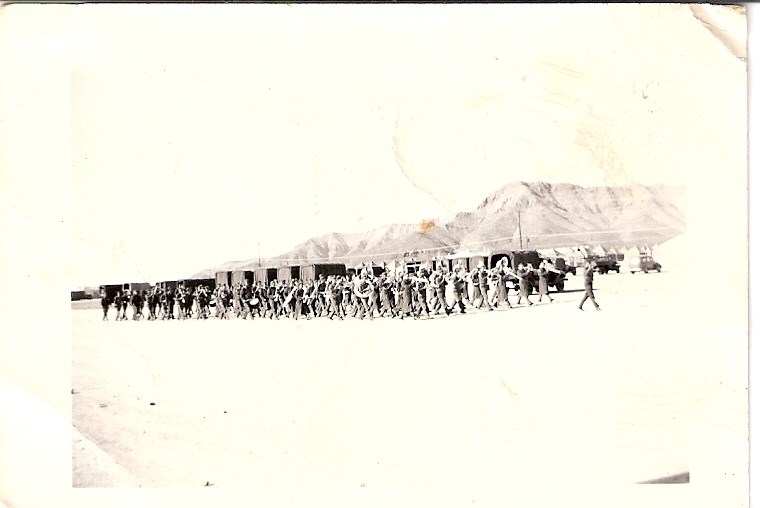

Thankfully, Daddy left a treasure trove of photographs that were taken during his military service. As far as I know, he never looked at the pictures after they were initially taken. They were preserved in an old scrapbook that his mother, Beadie Johnson, or my mother probably put together. The scrapbook contained valuable clues to his war years. This scrapbook wound up in my possession as one of my first choices when we divided up our inheritance. Mother left many pictures too, and I have her scrapbook. I decided that all of us should have copies of these pictures, at least on CD.

Later, I felt that the pictures and the information had to be put into some kind of context and labeled, if possible. But how could I accomplish that? The answer came in two incredible pieces of luck. One was a book, the other a phone call from Heaven. The book, The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War II by Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, is THE definitive book on the campaign in the Aleutians, where Daddy served. Sandy Beauchamp told me about and praised this book as the top source to go to for facts on the subject. I located it at the Laman Library in North Little Rock, but was not allowed to check it out. Ultimately, I located a copy of the book to purchase online. It came from a used book store in, of all places, Russellville, Arkansas. This is not so surprising when you learn that a good portion of the 206th Coast Artillery, Daddy’s unit, came straight out of Arkansas Tech University at Russellville. So this book gave me everything I needed to know about the history of the 206th from Marianna during the war.

The aforementioned phone call, as far as I am concerned, fits into the category of “Miracles.” About 8:00 p.m. December 4 one Tuesday evening, about two weeks after the article on the Veterans History Project appeared in the Marianna paper, I received a call from a Dr. Bob Boon of Huntsville, Alabama. He identified himself and stated that he was “your father’s hut mate all through the war and best man at your parents’ wedding.” I nearly fainted from shock. Although I had not heard that name in many years, the thought that ran my head was “Jackpot!” Who better to fill in those pesky gaps in history and provide color commentary for that portion of Daddy’s life than one who knew him better than anyone else at that time? Also, from their time as pups in the Arkansas National Guard Band in Marianna to the time that they were on their way home at war’s end Dad and Dr. Boon marched together in lockstep.

I kept Dr. Boon on the phone for more than an hour peppering him with questions which he untiringly answered. Since he was 86 years old at the time and his wife is a few years younger, Dr. Boon told me that he would be unable to make any of the interviews in Marianna anytime soon. I stated then that I hoped we could get together sometime in the future so that I could get his story for the Veterans Project. The future was on that Friday, which coincidentally was December 7, the 66th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor bombing. Bill and I decided that we could not let this opportunity pass by, so we packed and headed toward Huntsville.

On Friday morning December 7, 2007 Dr. Boon, his wife Eloise, and their daughter Hannah met with us and graciously allowed us to take over their lovely home and monopolize their day, although they seemed to enjoy it as much as we did. Both Hannah and Mrs. Boon sat right with us as we interviewed Dr. Boon, rapt with attention the whole time.

After we finished with the formal interview, Dr. Boon brought out his own scrapbooks and let us all look at them. He possessed many of the same photos that Dad had in his scrapbooks, but there was enough variation in them to make it interesting. These served as a springboard to more memories and stories of the 206th Band. He also identified many of the people and places in the pictures that I had. Later, the Boons took us out for a lovely lunch. With everyone more relaxed, Dr. Boon gave us information that made me wish the camera was still rolling. Dr. Boon seemed to possess total recall about that era. Although he is a very different man than my own father, Bob Johnson, in terms of personality, I came away from our meeting feeling as if I had spent the morning with Daddy.

The general facts of the Marianna boys entry into the war and other insights were confirmed by Roy V. Williams, also of Huntsville and former Marianna resident and veteran. After spending the morning with the Boons, we spent another wonderful time that afternoon with Roy and his delightful wife, Madeline, an old friend and classmate of Mother’s.

Armed with all of this sudden new knowledge, I felt compelled to get it all down on paper in some sort of coherent narrative, for all of us and for future generations. They will study World War II in school and we all should know what a vital part both of our parents played in that war, the outcome of which meant so much to civilization.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone who shared memories, stories, and general knowledge: Aunt Lois Barnett Duke, Aunt Sue Holman, and Sandy Beauchamp, who spent a lifetime picking the brain of her father, Ralph. Robin, Camille, and Kim willingly shared what they could remember from the little that Mother and Daddy told us. Their enthusiasm for what we have learned has made it all seem worthwhile.

Our daughters, Erin and Paisley, were equally enthusiastic and not once suggested that we were crazy for doing any of this. Paisley even stated, “Finally, you all are doing what you were meant to do all along….original field research.”

Dr. Bob, Eloise, and Hannah Boon offered hospitality, invaluable information, and friendship. Our family history project would have been shorter and less complete without them. I owe a great debt to Dr. Bob.

Mostly, credit goes to Bill, who did the heavy lifting as well as the encouraging of the project. He served as cameraman and sound man for the video. Bill also performed his specialty, which is combing the Internet for facts, figures, and minutiae, as if this project was important to more than just this family.

I am eternally grateful for and to Bob and Shirley Allen Johnson. They were good people and modest people. Neither of them were particularly shy, but they weren’t boastful either. This is one of the reasons that we have so little information what they felt they had to do and did it well, without much complaint. They got through it mostly intact. Probably because both of them had been in information-sensitive areas and had been trained and warned not to talk freely, they were never comfortable telling all that they knew or experienced. Besides, they would say, so many other people had it so much worse.

But for Sgt. Bob Johnson and Civilian War Worker Shirley Allen, their survival skills and their eventual attraction to each other, none of us would be here. It is a story worth telling.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

Bob Johnson's War

None of Bob Johnson’s children have any idea what it’s like to have a father who bragged about his war exploits. He just didn’t talk about it. His service was longer than most other men who were in the war. He didn’t seem to feel inferior to those who saw tremendous amounts of action. Nor did anyone who knew him treat him that way. Twice he was selected to serve as commander of his local American Legion post, the Julius Benham Post of Marianna, Arkansas. One of these times was in l950, a mere four years after World War II.

But if Stephanie, Camille, Robin, or Kim asked him “What did you do in the war, Daddy?” he most often answered, “I played in the band” or more specifically, “I played the trombone.”

He shouldn’t have had to go to into the service at all. He was color blind, an automatic and permanent 4F classification. His children went through many years wondering why their father thought all shades of tan through pink were just “brown.” Or why sometimes he studied both traffic lights and patterns before coming to a stop at an intersection. Finally, one day he mentioned to a roomful of us that he was color blind.

Now there was a conversation stopper! Stephanie, in particular, could not understand how he possibly could have been taken into the service if he were color blind. “Isn’t that supposed to exempt you from service?”

He shook his head and said matter-of-factly, “They needed recruits. They held up a gun and said, ‘Boy, do you see this gun?’ I said I did, and that was their eye test.”

The few times that Bob Johnson talked with his children about his military experiences, he did not sugar-coat anything. He did not particularly enjoy the experience, but he tried to make the best of it. When pressed, he would offer a snippet of information, such as how he admired the emergency military tactics of Regimental Commander Colonel, later to become General, Robertson. Or he’d distract the listener with a funny story, such as the one about Army buddy and fellow band member Van “Sugar Lump” Brown and the slop jar.

It seems that Sugar Lump joined the 206th Coast Artillery Band with the rest of the Marianna guys. Everyone liked Sugar Lump, but he had a knack for finding bad luck. Plus, he wasn’t much of a musician. Sugar Lump was tried out on a variety of band instruments and found lacking on all of them. When asked what instrument Sugar Lump wound up playing, Dr. Robert Boon said in a derisive manner, “Cymbals!”

By the time the 206th Band was in Dutch Harbor, Unalaska the Sugar Lump problem was solved by issuing him a clarinet, but no reed. Dad reported that frequently the band was required to march through the base before dawn, playing loudly in an effort to wake up the rest of the army. On one particular day as they marched by the barracks, an irritated soldier threw a nearly full chamber pot out the window in the direction of the band. Sugar Lump was the unfortunate clarinet-holder who took the brunt of it.

As Dad described the aftermath, he said that Sugar Lump came to him, crying. He said, “Dang it, Bobby! They hit me and I wadn’t even playing!” Gales of laughter by Daddy, Mother, and anyone in earshot would follow, no matter how many times the story was told. I was an adult before it occurred to me that this story was a defense mechanism for Dad. It was a story that deflected serious questions about the war, and it was a story that allowed him to laugh about the war, some of his experiences, and to feel a closeness to old army buddies who supplied friendship and protection during a trying time in their lives.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

Long Ago and Far Away: The Early Years

Bob Johnson was in college at Magnolia A&M before the war broke out. It was at the end of the Depression and he was a slightly older than the average underclassmen, having been born July 18, l918 and having repeated three grades in school. He repeated first grade due to an accident that nearly killed him and left him with a head injury that took months to recover from.

In that accident, he was riding the school bus, more like a wagon, he said. His father, Floyd, was the bus driver. Bob was standing at the door of the bus when they hit a bump that bounced the door open and Bob out. The bus ran over his head. He was unconscious for several days, maybe more than a week. Everyone attributed his survival and eventual recovery to the fact that he was wearing a little cap that buffered the weight of the vehicle and caused the tire to slide off his head. Also, recent rains had left the road muddy and softer. Whatever the reason, he pulled out of it, but lost enough school time that he had to repeat first grade. And for the rest of his life, he hardly ever left home without a cap.

He lost another year when his family moved from Oak Forest to Marianna. Oak Forest was several classifications below the Marianna Schools. The Oak Forest school was undoubtedly a one-room schoolhouse. The transfer to the larger school meant an automatic repetition that allowed the transferring students to “catch up” to the Marianna students. However, as an aside, I never heard anything about his older sister, Willastein, having to repeat a grade, and she transferred right along with Bob.

The birth order of the family was Willastein, Bob, Lois, and baby sister, Floyd Estelle.

You've Gotta Be a Football Hero

Bob Johnson was a wonderful athlete, small, but lightning fast and a quick thinker. He was a natural quarterback, although he usually played both offense and defense in Marianna games. His children heard of his athletic prowess throughout his life from people who saw him play. At his funeral in 1998 men from every walk of life in Lee County came up and talked about his exploits on the field or court, events that happened 50 years prior! Stephanie, Camille, and Robin’s old high school principal had been a teacher when Bob was in school. Clyde Hogan told them, “The thing about Bob Johnson and sports was he didn’t know when to quit. It made him dangerous.” It seemed to be a characteristic that stayed with him.

His senior year in high school, Dad said, he had a great football year. Every year he played was a great year, but that one was exceptional. At 5’4” and 117 pounds, he was the smallest guy on the team, but still its quarterback. And he played on teams with several athletes who went on to play at Division I colleges. A couple of his teammates, Kay and Butler Eakin were stars at the University of Arkansas, and Kay went on to a career in the pros.

But Bob was a standout, so much so that late in his senior year the football coach suggested that if Bob returned to play another year, in the hope that he would grow, the coach could almost guarantee him a football scholarship to college. So on his graduation night, his parents, Floyd and Beadie, showed up at the ceremony to watch with pride their second child and only son step up and collect his diploma. Only he didn’t. Later they discovered that he had deliberately flunked a course that made graduation impossible so that he could come back another year to play ball.

My grandmother, Beadie, told me once that it upset them so much that Floyd went to have a talk with the coach and threatened to withhold Bob from playing ball for him. Here it was the Depression and every kid still at home and not working or doing something else productive was a real drain on resources. Evidently Bob talked them into relenting because when fall arrived he was back on the football field, barking plays. He graduated that spring, a 20-year-old recent high school graduate, still 5’4”, 117 pounds and too tiny to attract any college football coaches.

He apparently graduated in 1939. Stephanie has in her possession a 1939 T.A. Futrall High School Diploma with Bob Johnson’s name on it. The Class Roll also contains the names of many people that Dad spoke of over the years as his boyhood friends: Bobby Boon, Maxcy Daggett, Dan Felton, Julia Jackson (Ju-Ju) Hughey, Margie Oxner Gardner, W. T. Webster, Dan Wood, and George Word.

Bob’s sister, Willastein, and her husband, Jess Odom, were living in Magnolia, Arkansas at the time where Jess managed a West Department store. They invited Bob to move in with them so that he could attend college at Magnolia A&M, now Southern State. Jess took Bob to visit the Muleriders’ football coach for an interview and a try-out for the team. Jess was an ace salesman and did his best to sell the idea to the coach that this small young man could stay on the field with college athletes, even to lead them. Bob told Stephanie that “the coach just laughed. Then he told me and Jess that he couldn’t in good conscience put me on the field because those big ole boys would kill me the first time they hit me.”

Bob said that he coach must have seen his disappointment because he offered to let Bob be the equipment manager and to drive the bus. Bob accepted the job, since he would get paid for it. Undoubtedly, it was hard on him to wash jerseys for the players and cart them to games when he wanted so much to be on the field with them. He did put his athletic skills to use by joining the boxing team. He continued boxing in college and, I believe, in the Army right up until he lost a fight, by being knocked out cold. That ended that.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

I Love a Parade: Why the Guard?

Though no one in the family can remember hearing Bob say exactly why or when he joined the National Guard, Dr. Robert H. “Bob” Boon of Huntsville, Alabama, now 86, does remember. Eyewitness Boon reported in a December 7, 2007 interview from his home in Huntsville, Alabama that most of the young men who joined in Lee County at that time did it for the money and for fun. The country was still in the grips of the Depression and the $1 per drill that was offered looked pretty good. “We wanted to learn music and we got a check And we had fantasies about getting away from home.”

In Marianna, Arkansas the National Guard unit was the 206th Coast Artillery. They trained once a month and kept their World War I vintage equipment ready in case foreign enemies marched up the St. Francis and L’Anguille Rivers looking for trouble.

A more basic mission was to assist the populace in case of natural disasters, which they were called upon to do in the Great Flood of l937. The Guard went out to search for and bring to safety the many farm families who lived in the bottoms, the lands adjacent to the Mississippi and St. Francis Rivers and their tributaries. These rivers flooded nearly every year until the Army Corps of Engineers completed their levee and drainage projects. The ‘37 flood was particularly bad and people had to be evacuated to the football stadium and put up in tents for a while. The Guard supervised the operations and Bob took part in that. (Boon)

The Arkansas National Guard Yearbook of 1938 includes a formal regimental photograph of the 206th Coast Artillery. The photo includes the “men” of the 206th, many of whom people of my generation will remember. They are W. R. Jones (Maria and Billy Bob’s father), Ed Spaine (Sharon and Ned’s father), Ralph and Harold Brainard, Robert Boon John Summerford, Cliff Williams (Carol and Pat’s father), Irvin Carlow (Chris and Bill’s father), Ralph Beauchamp (Sandy and Jack’s dad), Courtney Langston (Lynn, Martha Marie, and Sam’s dad), Cliff Harrington (Dusty and Georgia’s dad) Luther McCarty (James, Patricia, Linda, and Donny’s father), along with Robert T. Johnson.

These men became leaders of their community after the war, but in l938 they were just babies. And they had no inkling that they were about to enter the world arena. At the time they were just looking for something to do.

Plus, Dr. Boon continued, in the case of the band, “The Guard provided the instruments for the band. We wound up being a sort of combination Guard band and community band. We’d march downtown and kids would run and squeal. People would gather. It was something to do.” The band regiment was headquartered in Marianna, so they didn‘t have to find transportation to fulfill their responsibilities.

Bob Johnson was three years older than Bobby Boon, but due to his graduating later than he should have, it is likely that he was still a high school student when he enlisted. Robert Boon definitely remembers being in high school, and underage, when he joined.

The band was recruited by a band master called “the Professor” by the young men he trained. He was a man named Fred H. Kreyer and had a degree in music. According to Boon and Roy V. Williams, another member of the Guard Band, some of the band members “fudged” on their ages. One had to be 18 to join. Williams said that he was 17 and Boon barely 16 when they signed on, yet they said it wasn’t a problem for them. Both were the company clerks at one time or another and could cover up the truth about their ages. (Williams)

So these recruits, our father included, signed on for “a lark.” Boon stated further, “We thought we’d make a little money, and in case of war, we wouldn’t have to do anything unpleasant, like be in the infantry.”

The prospect of these young men being caught up in a world war didn’t seem to be a possibility at the time. Boon reports that they completed their basic training in Pensacola, Florida in the summer, which for the band mostly consisted of getting better at playing their instruments. It also gave them the opportunity “to get away for the summer and carouse with our friends,” Boon recalled. For those Guardsmen who wound up in the artillery units, they practiced shooting their World War I era artillery equipment which was wildly inaccurate, into the Gulf of Mexico.

The 206th Coast Artillery was notified in August of l940 that they were being sent to Minnesota. for training before being sent for specialized training. Col. Robertson, their regimental commander gave all who were in college the option of getting out of the Guard. But because the draft had been instituted and their Guard commitment was just one year, few took that option. Several opted to stay rather than risk the draft. (Boon)

So these young fellows had, in all innocence, volunteered to protect their home counties and entertain them with military parades for one year. They were farm boys, clerks, craftsmen, and students. Here, it seems appropriate to paraphrase the Gilligan’s Island Theme Song. They signed up for “a one year tour….A one year tour.”

The joke was on them. Activated in January 1941, they would not see home again as civilians until half-way through 1945. They wound up going to Ft. Bliss in El Paso, Texas for training and then to Dutch Harbor, Alaska. In the ramp up for the war, the 206th Coast Artillery was federalized, sent to Texas, and made their way to Alaska as Army National Guard troops. Many of the young men, including my father, were there for the war’s duration.

This is Part 1 of "What Daddy and Mother did in the War." Read Part 2 next.

Last updated: July 18, 2025