Last updated: February 18, 2021

Article

Beyond New Mexico and Missouri: The Diverse People and Places of the Santa Fe Trail

It took all kinds of people to make the Santa Fe Trail successful. Hispano businessmen in Santa Fe, Chihuahua, and New York helped arrange credit, complete sales, and transport goods. American Indians also participated in the trade, as did Jewish merchants. Many free Blacks ran their own businesses, employing both Blacks and whites to make important items like wagons or ox yokes. Enslaved people performed an array of trail-related jobs. Irish and German immigrants served as laborers, craftsmen, and merchants. Businesses related to the trade, like hotels and shops, were usually run by women.

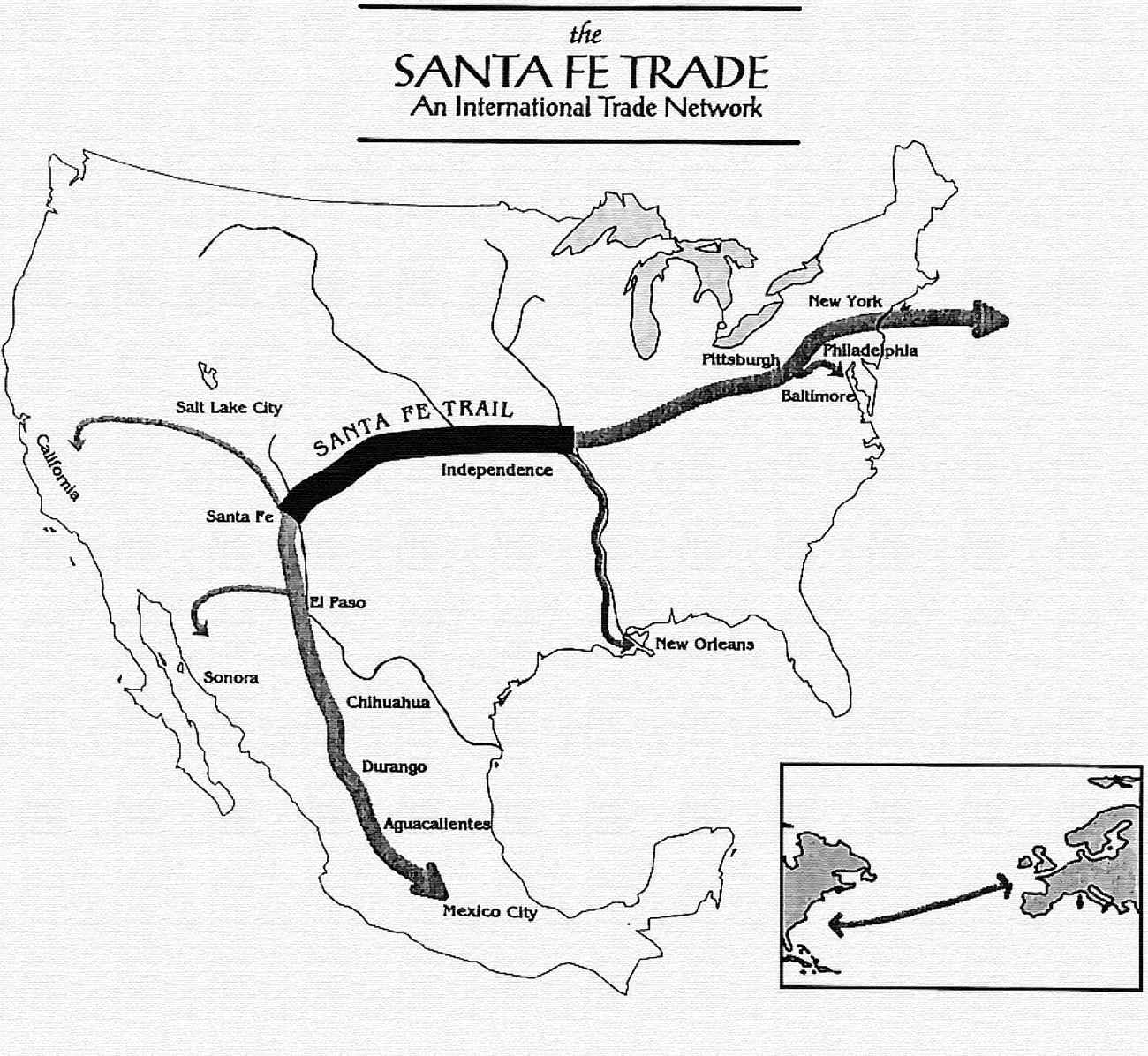

Like its cast of characters, the trail’s geographic reach was broader than we imagine. At the most basic level, manufactured goods (like cloth) flowed towards Santa Fe, while raw materials (like wool) and Mexican silver flowed towards Missouri. Yet the reality is a lot more complicated. The trail’s economic network included places as far-flung as Chihuahua, New York, and London. Goods bound for Santa Fe—many of them coming from overseas—were usually transported via steamboat to trailhead towns in Missouri, like Westport or Independence. From there, they would be loaded onto a wagon and driven roughly 800 miles to Santa Fe, which took anywhere from eight to ten weeks.

Map in Susan Calafate Boyle's NPS book, Comerciantes, Arrieros, y Peones: The Hispanos and the Santa Fe Trade

When we think of the Santa Fe Trail, we usually imagine wagons rolling across a prairie. Yet in some ways, it’s just as accurate to think of a bustling city like New York, Philadelphia, or Baltimore. These vital ports contained people responsible for inspecting international shipments, storing them safely, and loading them onto boats headed for Missouri. Some years, the Santa Fe trade favored certain cities; for example, in 1830, half of all imported goods bound for Santa Fe passed through Philadelphia. Pittsburgh also played an important role, both as a wagon manufacturing center and an access point for the Ohio River—an important water transportation route for goods headed westward. Closer to Santa Fe, St. Louis and its skilled tradesmen supplied parties preparing for the Oregon, California, or Santa Fe trails.

Santa Fe Trail merchants didn’t always do business remotely. In the 1830s, New Mexican merchants began making annual trips to places like Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York to purchase goods directly from suppliers. Businesses and newspapers in these cities realized the importance of these visits, and they used advertisements to entice them. The Mexican American War (1846-48) had little effect on this pattern; in fact, the war actually helped Hispano businessmen by increasing the presence of the US federal government (especially the US Army) in and around New Mexico. Contracts to supply Army forts provided New Mexican merchants with cash or credit that they used to pay commission merchants—people who assisted in purchasing and transporting goods—in far-away cities like New York.

Santa Fe Trail merchants became part of an ever-expanding web of information. In 1841, the nation’s first credit reporting firm was founded in New York City; within ten years, it had 2,000 agents across the United States regularly submitting information. The agency kept records on Jackson County, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico, which helped lenders decide whether or not to lend money to certain trail merchants. New York was also home to the important firm of Peter Harmony and Nephews, commission merchants for a number of Santa Fe Trail traders. The founder, Peter Harmony, owned numerous properties in Manhattan and belonged to prestigious social clubs. The firm also did business in Europe, Cuba, and Brazil, and they kept their records of the Santa Fe trade in Spanish. One particularly wealthy New Mexican merchant, acting on Peter Harmony’s advice, bought houses in New York as an investment.

The Santa Fe Trail connected people across great distances. Although the trail itself ran between New Mexico and Missouri, it would not have functioned without Boston’s docks, Pittsburgh’s wagon makers, or even England’s cotton mills. It took all kinds of people, in all kinds of places.