Last updated: February 13, 2025

Article

Black History in the Last Frontier: Thomas Stokes Bevers

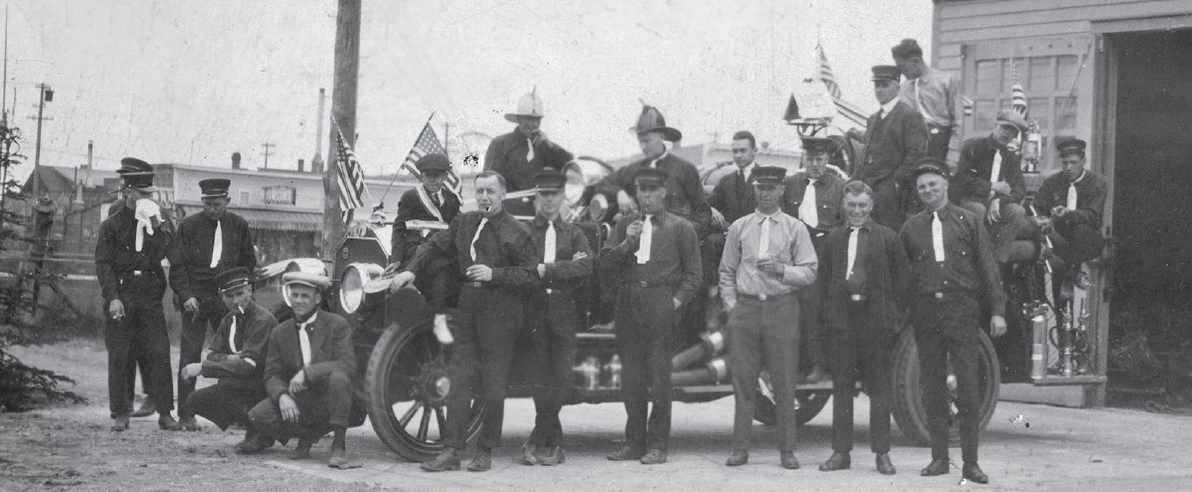

Carl Lottsfeldt Collection (Anchorage Museum B1978.111.26).

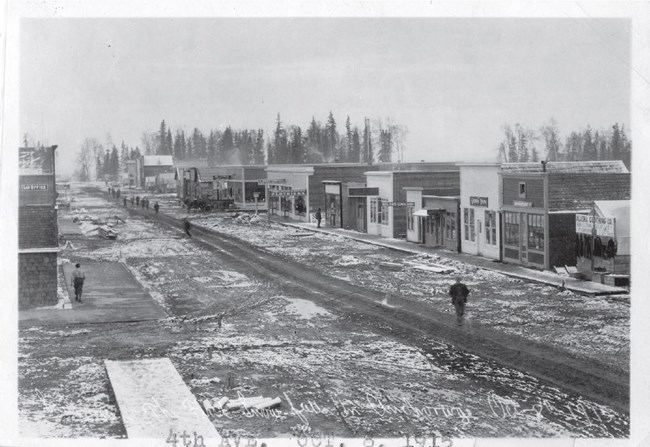

Alaska Railroad and Engineering Commission (Anchorage Museum B1963_016_006).

Heading West after World War I

In his late twenties, Bevers left Virginia to enlist as a soldier in the First World War at a time when the nation’s Armed Forces remained segregated. When Bevers completed his service, he headed West, settling in Seattle in 1920 before relocating to Anchorage, Alaska in 1921.

Making a New Life in Anchorage

In Anchorage, he found a city with opportunities that evaded him elsewhere. During that time, the federally owned and operated Alaska Railroad held great sway over the town’s economy. Perhaps fearing the town’s settlers would treat him harshly if they knew of his ancestry, Bevers kept his identity as a mixed-race black man to himself.Before settlers named it Anchorage, the Dena’ina referred to the land as Dgheyaytnu, and it functioned largely as a seasonal fish camp. The indigenous population that settled southcentral Alaska had been in the area for thousands of years. White settlers arrived in larger number only in 1915 as construction began on the Alaska Railroad. The region’s black population remained nil. In fact, few black people traveled to Anchorage at first, but the population steadily grew in the decades to come. Bevers was certainly among the earliest African Americans to have arrived in Anchorage and one of the few who seemed to have stayed.

Alaska Railroad and Engineering Commission

(Anchorage Museum B1962_007_2).

Anchorage’s First Paid Firefighter

Thomas Bevers was active in Anchorage’s civic life, volunteering as a firefighter and working as a blacksmith. Before long, Bevers earned the respect of his fellow firefighters, and in 1922 he became Anchorage’s first paid fireman. In 1927, he became Chief of the Fire Department, and with the support of his fellow firefighters, Bevers asked for and received a pay raise from $155 to $175 a month. He served as fire chief until he retired in 1940.

Community Leader and Founder of Fur Rendezvous

In addition to fighting fires, Bevers took an interest in fur trading, and along with several other investors, he purchased eight acres of land between 10th and M Street, now a part of downtown Anchorage. Bevers’s fur farm and trading post culminated in Anchorage’s location as a key center for Alaska’s fur trading industry. Two decades later, Bevers, along with others in the young community, initiated an annual fur trading exposition, an event Alaskans recognize today as Fur Rendezvous. In the early 1940s, Bevers won a seat on the City Council and served two terms.In 1944, Tom Bevers died unexpectedly, likely due to a heart attack, while on a hunting trip. By that time, he had ascended Anchorage’s social ladder and was revered throughout the community. “Anchorage has lost one of its best friends and leaders,” eulogized the Anchorage Daily Times. After his death, many in town were surprised to find out that his family was black. Only after his sister, who reportedly had darker skin than Tom, arrived in Anchorage to settle his finances and prepare his body to be returned to Virginia, did Anchorage residents learn he was mixed-race. By that time though, Tom Bevers had accumulated the good will of his adopted community. Members of the local Elks Club and Masons lobbied to keep his remains in Anchorage and provide a proper funeral, a proposition to which his sister agreed. The Masons read the burial rites and laid Bevers to rest at the Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery, where one may find his gravesite today.