Last updated: July 24, 2023

Article

Building Climate Resilience

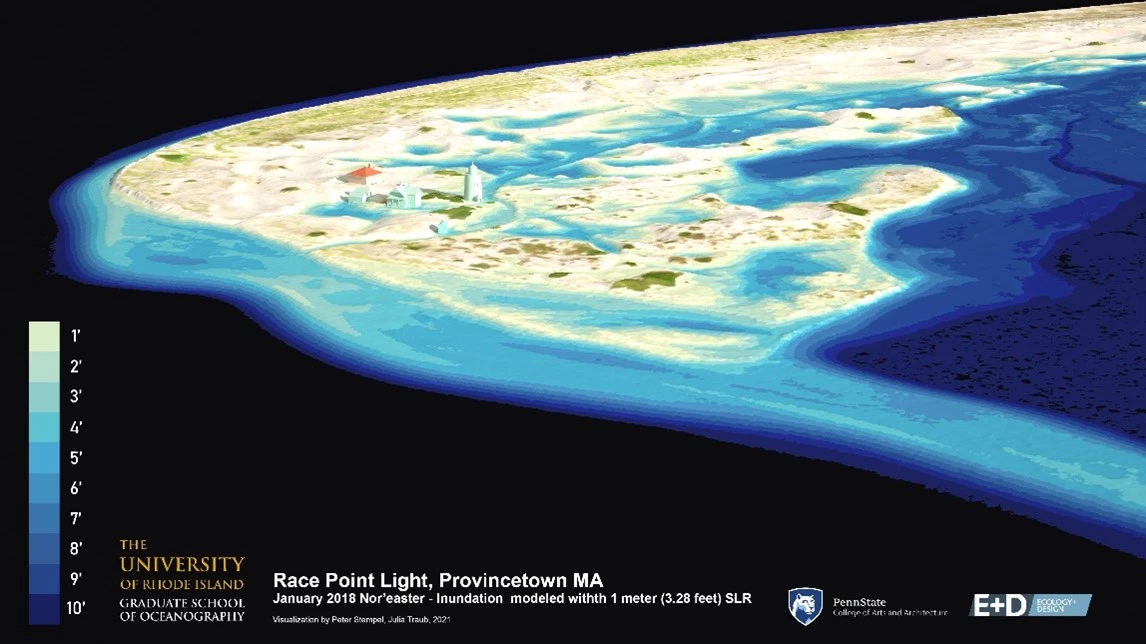

Visitors make their pilgrimages to Cape Cod National Seashore (CCNS) year-round to appreciate the landscape’s alluring natural beauty and maritime culture, but there is no guarantee that such iconic views and sites are lasting. As with other conservation areas across the globe, climate change is proving its immediacy here at CCNS. Warmer average temperatures lead to sea level rise, which when aggravated by an aggressive storm can threaten the vitality of the pristine beaches, picturesque dunes, historic lighthouses, and woodland ecosystems home to the park. With resources and safety at stake, actions to enhance resilience and adaptation are necessary to ensure this sandbar stands the test of time.

Left image

Visualization of Race Point Light in Provincetown, MA, in normal conditions.

Credit: The Impact of Sea Level Rise During Nor’easters in New England, May 2023 (Unpublished report, in peer review stage)

Right image

Visualization of Race Point Light in Provincetown, MA, with 1m sea level rise.

Credit: The Impact of Sea Level Rise During Nor’easters in New England, May 2023 (Unpublished report, in peer review stage)

The Challenges of Shifting Coastlines

“The only constant in life is change.” – Heraclitus, Greek Philosopher

The geology of Cape Cod is, in one word, dynamic. Natural features including the sandy dunes and kettle ponds stand today as evidence of the Cape’s glacial history. During significant geological events influencing the retreat of glacial ice, the land mass of Cape Cod has shifted continuously. And now, as many scientists note another transformative age for the planet, the Cape is experiencing dramatic changes at an accelerated rate.

According to a 2022 interagency report led by NOAA, sea levels on the U.S. East Coast are estimated to increase by 10-14 inches over the next thirty years. The implications, as the report states, is that "by 2050, 'moderate' (typically damaging) flooding is expected to occur, on average, more than 10 times as often as it does today and can be intensified by local factors." Notably, low-lying coastal towns are regions of special concern given this possibility of flooding. Sea level rise, combined with intense storms, accelerate erosion, threatening the Cape's sandy cliffs and the structures that lie above them.

Already, Cape Cod National Seashore is watching these shifts increase. In 2018, a series of nor’easters came for the Outer Cape, battering the coastline, eroding the dunes, and compromising beach parking. While CCNS facilities most clearly suffered from the storms, the natural habitat found within Cape Cod also wavered in the face of climate change and the vast damage it could cause to wildlife and humans alike.

Scrambling for fast-acting solutions, municipal and federal leaders across the Cape have had to reconsider their long-term hazard and climate adaptation plans and implement alternative proactive strategies geared towards preventing the worst-case scenario. Rather than just robust emergency response, stakeholders confronted the reality that as sea level rises, more coastal flooding will be expected in existing and new areas. Because of this projection, and the anticipation of more intensive rainfall events and wind damage, the need to prepare for erosion, land, and habitat loss actualized. Sustained high levels of Park visitation and use, too, intensifies the threat. The question of what could be done needed to be addressed.

Motivated to act fast, CCNS was requested to contribute to a pilot study led by the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). In the short-term, the project sought to examine the vulnerability of coastal park infrastructure, specific to energy, communications, transportation, and water systems with the intent of increasing the potential for the park to respond to and recover from climate effects. Examining the potential impacts and their likelihood of occurrence, researchers at NREL could help the park prioritize risks relevant to CCNS and identify effective adaptation strategies for consideration. Once researchers completed the report in 2020, CCNS had a resilience preparedness prioritized matrix to inform planning decisions internally and with other federal agencies and local municipalities.

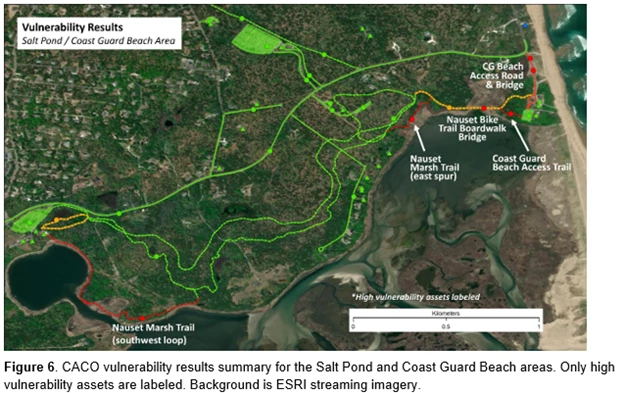

To be optimally prepared, park managers referenced additional research and data to inform their resiliency approach on park facility and transportation assets. While taking on structural developments and reinforcements, CCNS has continued to collaborate with institutions regarding long term coastal resiliency planning. In 2018, the Seashore began working with researchers at Western Carolina University to project the vulnerability of facility and transportation assets at the park. Utilizing a Coastal Hazards and Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment Protocol, that is being done for all coastal parks, researchers were able to measure exposure and sensitivity to predict how infrastructure would fare over a 35-year planning horizon, until the year 2050.

Completed in 2022, the report included analysis of 225 buildings and structures (including visitor centers, lighthouses, houses/cottages, maintenance buildings, amphitheaters, and a dike) and 127 transportation assets (roads/road segments, parking lots, bridges, trails, and boardwalks) at CCNS. Referencing frameworks such as the recognized FEMA flood zones, 2021 USGS shoreline change rate data, and NOAA sea-level rise projections, researchers reported that 17% of the assets analyzed have high or moderate vulnerability to the evaluated coastal hazards and sea level rise while 79% have minimal vulnerability or are not in any of the evaluated hazard zones. Looking forward, the park planners and managers will explore the guidance to inform future adaptation and construction projects.

Additionally, the Seashore collaborates with municipalities on shared concerns like the condition and sustainability of low-lying roads. As a result of climate change and projected sea level rise, the fifteen towns of Barnstable County must plan strategically in anticipation of damage to their interconnected roadway system. Led by the Cape Cod Commission and through the Massachusetts Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness program, the Low-Lying Roads project seeks to identify challenges to transportation systems and enact effective adaptations in the event of sea level rise. After each town chooses their top two road segments at risk of flooding, the project will collaborate on design solutions aimed at implementing long term and resilient infrastructure. In Wellfleet and Provincetown, vulnerable roadways identified transect park property. CCNS’s participation on this matter, therefore, is necessary. This work is complementary to the four-town intermunicipal bay shoreline management planning funded by MA Coastal Zone Management. The four Outer Cape towns are using science-based analyses to assess sea level rise scenarios, flood mitigation designs for selected low-lying roads, and regional sand banking. Together they are developing robust shoreline management datasets and uniform standards for coastal management.

ESRI

Acting Fast & Preparing for the Future

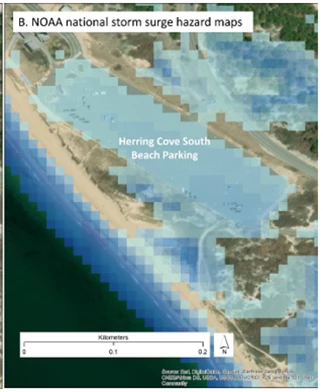

A particularly vulnerable landscape to sea level rise, flooding, and erosion, CCNS recognizes the need to adapt to a changing climate or risk facing irreparable damage to its historic sites and landmarks. Factoring in research findings, park management underwent plans to reposition and build facilities at the popular Nauset Light Beach. Threatened by an erosion rate of 12-15 feet per year over a several year period, CCNS began constructing the new bathhouse facility at the far end of the parking area, completed recently in August 2022. The project, like others at the park, exemplifies the vast efforts to maintain the character of the National Seashore. It came after a 2019 realignment of Province Lands Road and the relocation of the Herring Cove Beach North Parking Lot, also in response to sea level rise and flooding threats.

Though critical in ensuring continued use and immediate access, structural projects like road and facility repair tend to be reactive solutions, following a significant weather event. Proactive plans identify a risk and seek to address its projected impact. Oftentimes, these methods involve Nature Based Solutions, best practices that consider natural means for obtaining sustainable resilience. The Herring River project falls into this bucket as it aims to resolve ongoing environmental issues through healthy habitat restoration.

Once a vast salt marsh habitat, the Herring River in Wellfleet transitioned to a freshwater woodland rampant with invasive species such as the pesky phragmites. After a concentrated effort by multiple federal, state, town, and NGO stakeholders to initiate a restoration process, the project finally broke ground in the fall of 2022. A multi-year project, the restoration began with invasive vegetative removal as to encourage room for native species to grow. The project then transitioned to dike demolition and bridge construction. By opening the tidal flow under the new bridge and related culvert and water control upgrades, salt water will be reintegrated in the Herring River, restoring the land to the salt marsh it once was. Vibrant vegetation such as salt marsh cord grass native to the Cape wetlands play a significant role in filtering nutrients and pollutants, as well as storing carbon at a rate higher even than that of tropical forests. Being one of the biggest restoration processes of its caliber globally, scientists will follow the progress of the Herring River project to determine its potential in enhancing the resiliency and longevity of the Cape’s iconic ecology.

In considering coastal resiliency, the benefits of salt marsh habitat to the climate cannot be ignored. Frequently deemed a “carbon vacuum,” salt marsh reduces an estimated 4,018,572 grams of carbon dioxide equivalents per acre per year. Additionally, salt marsh grasses and vegetation have the super ability of holding onto sediment in the roots, thereby stabilizing the sea floor, slowing wave motion, and mitigating erosion and land loss. Because of a salt marsh’s sponge effect, it can act as a soak up excess water, meaning it has potential to buffer and significantly reduce flooding damage.

Though the prospect of sea level rise and subsequent flooding may seem daunting, persistent collaboration and comprehensive environmental planning have proven the potential for innovative and successful restoration and preservation. Participation from various actors, too, stand to showcase that the people of the Cape are not keen on the idea of losing it. In fact, they’ll do most anything to ensure this special place persists for future generations to enjoy and nurture.

NOAA