Last updated: March 9, 2022

Article

Captivity and Independence: Race and Enslavement in the Trailhead Towns Along the Missouri

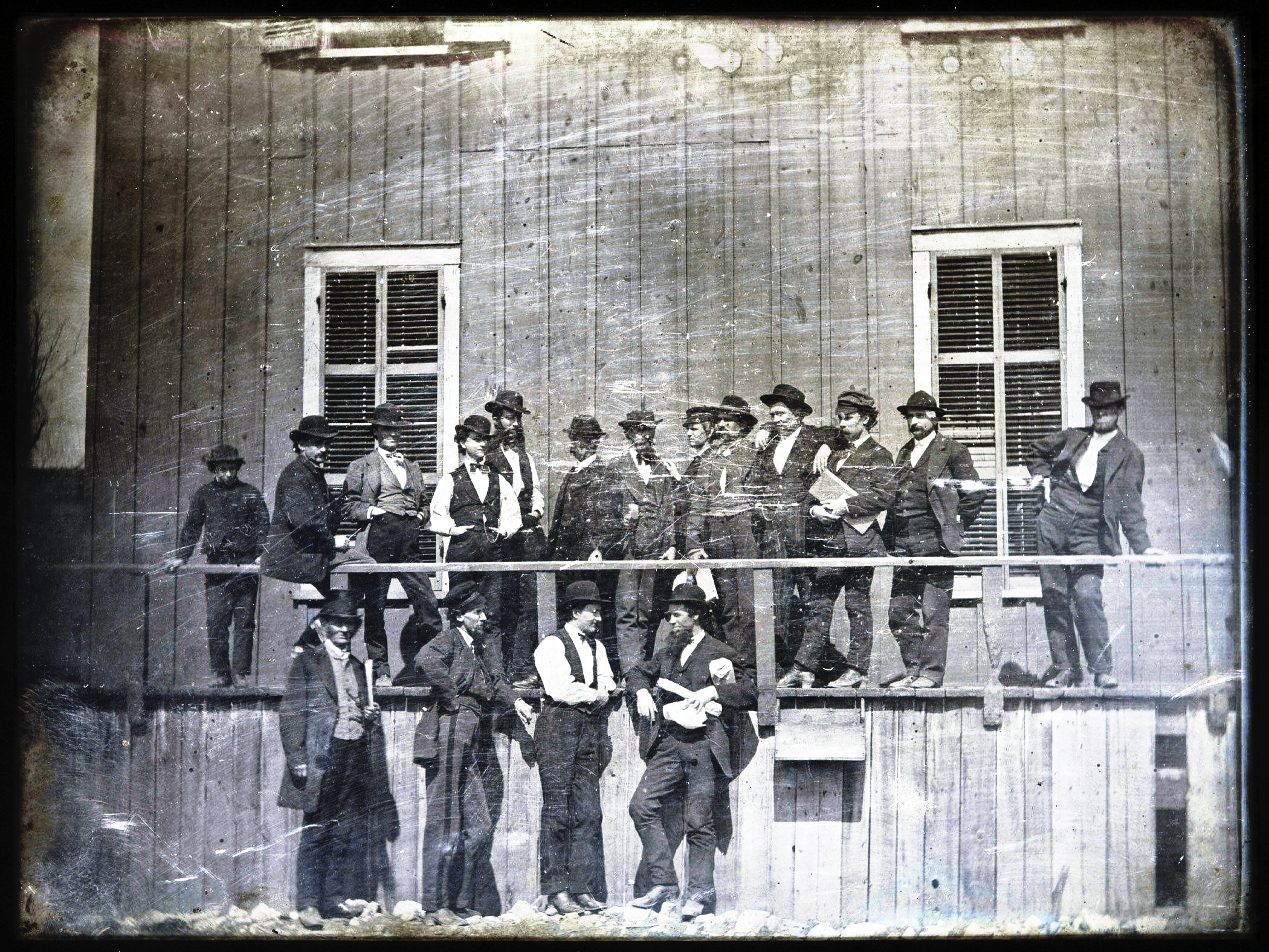

Photo/Public Domain

Westward travel in the nineteenth century conjures up ideas of freedom, independence, and fresh starts. But what about the towns where these westward travelers started their journeys? Were towns like Independence, Missouri—a town at the eastern end of the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe trails—actually places of independence for all?

Many overlanders began their journeys at one of many trailhead towns along the Missouri River. These were bustling places, with huge crowds, loud noises, and outlandish prices; there were hotels, stores, blacksmiths, livery stables, and other businesses for outfitting westward expeditions.

These trailhead towns on the Missouri straddled the border between the more densely-settled United States and the vast territory to the west. General lawlessness reigned, as gamblers, cheats, and thieves preyed on unsuspecting travelers. While in Westport, Kansas, historian Francis Parkman observed that “whiskey, by the way, circulates more freely…than is altogether safe in a place where every man carries a loaded pistol in his pocket.”

Trailhead towns like Westport were particularly inhospitable to Black Americans, even those that were not enslaved. Yes, jumping-off places were diverse communities that offered economic opportunities for people of color, such as Hiram Young and Emily Fisher. However, trailhead towns along the Missouri River carried the same anti-Black attitudes as much of the United States. Merchants, outfitters, hotels, and restaurants frequently refused their services to Black emigrants. Overland travelers usually joined wagon companies, pooling labor and capital to ensure a successful journey. Yet these companies did not often accept Black members, meaning that Black emigrants had to convince wagon companies to let them join. Many Black travelers thus spent extra money and time in the trailhead towns before beginning their journeys westward.

Free Black men and women had to exercise extreme caution along the Missouri River. The state of Missouri, home to the important jumping-off points of Independence and St. Joseph, was admitted to the Union as a slave state in 1821. Officials passed laws in 1835, 1843, and 1847 prohibiting freedpeople from entering Missouri. State law also required free Blacks already residing in Missouri to carry a license; otherwise, they could be fined or even imprisoned as runaway slaves. Essentially, Black people were presumed to be enslaved unless they could prove otherwise. Slave catchers operating along the Missouri border used a similar logic, capturing Black people and selling them into bondage—regardless of their legal status. (Slave catchers also operated in free states along the Missouri River, like Iowa.)

Despite these hazards, Black travelers visited jumping-off places voluntarily. The enslaved, however, had no choice—they simply accompanied their enslavers westward, often leaving their family and friends behind. If a traveler wished to acquire extra help for their journey, trailhead towns like St. Joseph and Independence regularly hosted public slave auctions; in fact, Independence’s auctions were held on the steps of its courthouse. The story of westward expansion is not simply one of personal liberty—captivity and bondage are essential to the narrative, as well. Although we associate jumping-off points with freedom and adventure, they have a more complicated legacy.

Shirley Ann Wilson Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains: African Americans on the Overland Trails, 1841-1869 (Santa Fe: National Trails Intermountain Region, 2012), 43-65.