Part of a series of articles titled Climate & History at Glacier National Park.

Article

Causes & Consequences of Climate Change at Glacier National Park

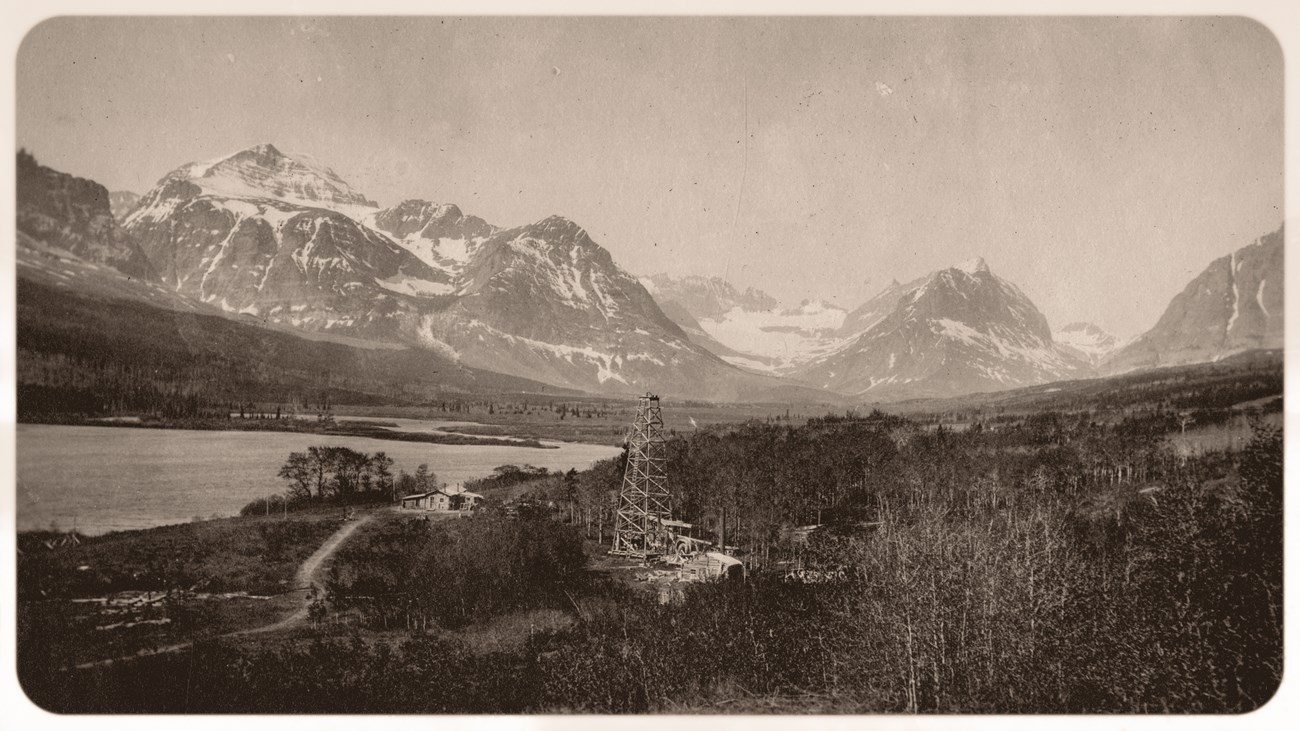

This photograph of the Many Glacier Valley in the early 20th century was donated by the Frisbee Family. The exact date and name of the photographer are unknown.

Before Glacier National Park was established in 1910, oil wells could be seen below active glaciers.

Both the causes and the consequences of climate change are intertwined here. Burning fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that warms the planet. High elevation areas like Logan Pass are warming much faster than the global average, causing glacier retreat here and around the globe. Since early drillers moved into this area the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen sharply.

If the old stories are true, early prospectors were lured to natural oil seeps in Glacier by bears that had wallowed in the “black gold.” In 1892, a local paper presumed that this was “the only case where bears have been the guides of men to valuable deposits beneath the surface of the earth.”

By the end of 1901, the Butte Oil Company had started drilling Montana’s first oil well at the head of Kintla Lake in what is now the northwest corner of the park. Others thought they would find fortune by drilling in the Many Glacier Valley.

In 2024, atmospheric CO2 reached 427 parts per million.

But the dream of riches did not pan out. One prospector was able to pipe just enough gas to burn for warmth in the winter. No one else did much better. The eager team at Kintla only ever found enough to get their hopes up. Then, sometime in the winter of 1902-1903, the accidental ignition of leaking gas sparked a fire that destroyed their whole operation. What little oil they had found, along with their buildings and equipment, went up in a cloud of black smoke.

The oil boom ended by the time the park was established, but carbon dioxide molecules released in that fire are still in the atmosphere, adding to the 421 parts per million (ppm) recorded in 2022, warming the Earth and melting the glaciers.

The oil boom ended by the time the park was established, but carbon dioxide molecules released in that fire are still in the atmosphere, adding to the 421 parts per million (ppm) recorded in 2022, warming the Earth and melting the glaciers.

NPS Lombardi

“The burning of coal, oil, and natural gas,” is releasing carbon dioxide and warming the climate, announced a 1965 report from the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. These changes “could be deleterious from the point of view of human beings,” the Johnson report cautioned.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that we should anticipate substantial climate change during the next several decades as a result of man’s impact on the composition of the atmosphere.” That was the warning from NASA scientist, Dr. James Hansen to Congress in March, 1982.

The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere reached 421 parts per million (ppm) in 2022, the highest concentration in human history. “We have known about this for half a century, and have failed to do anything meaningful about it,” said senior NOAA scientist, Pieter Tans.

The information in this article is featured in exhibits outside the Logan Pass Visitor Center. Check the exhibits out for yourself next time you visit!

DeSanto, Jerome. “Drilling at Kintla Lake: Montana’s First Oil Well.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 35, no. 1 (1985): 24–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4518869

“[Bear] hides were sold at Tobacco Plains (the vicinity of present-day Eureka), and the observation was made that the bear skins "exhaled the odor of kerosene." Soon it was discovered that oil floated on a pool of water near the shore of Kintla Lake and that bears were using the pool for a wallow.””

“The Bee observed, this was "apparently the only case where bears have been the guides of men to valuable deposits beneath the surface of the earth." Stories of the kerosene-soaked bears gained the attention of two groups of prospectors in late June of 1892.

“Then, sometime during the winter of 1902-1903, the accidental ignition of escaping gas and the burning of the rig slapped one last stroke of bad luck on the company. Almost the whole plant-derrick, cabins, sawmill, and equipment-was lost. The Butte Oil Company's investment of $40,000 had literally gone up in smoke.”

Robinson, Donald. 1960. “Through the Years In Glacier National Park: An Administrative History.” Glacier Natural History Association Inc. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/490209

1856. Foote, Eunice. “Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays” American Journal of Science and Arts. Pp. 382-383. https://archive.org/details/mobot31753002152491/page/381/mode/2up?view=theater

“An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature,”

Dr. James Hansen Testifies to Congress in 1982

http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2019/Planet.Chapters31-34.2019.06.18.pdf

1982. National Research Council. Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Second Assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18524

Pp. xv. “As residents of this most pleasant planet, we must necessarily be concerned about any changes in its heating and ventilation systems.”

“As we plan ways of meeting our energy needs from fossil fuel and alternative sources, it is thus prudent to consider the implications for atmospheric carbon dioxide, climate, agriculture, the natural biosphere, and indeed for our increasingly interdependent global society.”

Pp. 1. “For over a century, concern has been expressed that increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration could affect global climate by changing the heat balance of the atmosphere and Earth.”

Pp. 9. “The stubborn refusal of the CO2 problem to "go away" is in itself significant.”

June 3, 2022. NOAA “Carbon dioxide now more than 50% higher than pre-industrial levels”

https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/carbon-dioxide-now-more-than-50-higher-than-pre-industrial-levels

“Carbon dioxide measured at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory peaked for 2022 at 421 parts per million in May, pushing the atmosphere further into territory not seen for millions of years,”

“CO2 pollution is generated by burning fossil fuels for transportation and electrical generation, by cement manufacturing, deforestation, agriculture and many other practices. Along with other greenhouse gases, CO2 traps heat radiating from the planet’s surface that would otherwise escape into space, causing the planet’s atmosphere to warm steadily,”

“Prior to the Industrial Revolution, CO2 levels were consistently around 280 ppm for almost 6,000 years of human civilization. Since then, humans have generated an estimated 1.5 trillion tons of CO2 pollution, much of which will continue to warm the atmosphere for thousands of years.”

Pieter Tans, senior scientist with the Global Monitoring Laboratory. “We have known about this for half a century, and have failed to do anything meaningful about it."”

November 6, 2015. Olson. The Hill. “Fifty years ago: The White House knew all about climate change.”https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/energy-environment/259342-fifty-years-ago-the-white-house-knew-all-about-climate/

November 6, 1965. President Lyndon B. Johnson. “Statement by the President in Response to Science Advisory Committee Report on Pollution of Air, Soil, and Waters.” https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-the-president-response-science-advisory-committee-report-pollution-air-soil-and

“Carbon dioxide is being added to the earth's atmosphere by the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas at the rate of 6 billion tons a year. By the year 2000 there will be about 25 percent more carbon dioxide in our atmosphere than at present. Exhausts and other releases from automobiles contribute a major share to the generation of smog.”

November 1965. Report of the Environmental Pollution Panel, President's Science Advisory Committee. "Restoring the Quality of Our Environment" (Government Printing Office, 317 PP.). https://legacy-assets.eenews.net/open_files/assets/2019/01/11/document_cw_01.pdf

Pp. 112. “Only about one two-thousandth of the atmosphere and one ten thousandth of the ocean are carbon dioxide. Yet to living creatures, these small fractions are of vital importance.”

“All fuels used by man consist of carbon compounds produced by ancient or modern plants. The energy they contain was originally solar energy, transmuted through the biochemical process called photosynthesis. The carbon in every barrel of oil and every lump of coal, as well as in every block of limestone, was once present in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.”

Pp. 112-113. “A small fraction of this organic matter was transformed into the concentrated deposits we call coal, petroleum, oil shales, tar sands, or natural gas. These are the fossil fuels that power the world-wide industrial civilization of our time. Throughout most of the half-million years of man's existence on earth, his fuels consisted of wood and other remains of plants which had grown only a few years before they were burned. The effect of this burning on the content of atmospheric carbon dioxide was negligible, because it only slightly speeded up the natural decay processes that continually recycle carbon from the biosphere to the atmosphere. During the last few centuries, however, man has begun to burn the fossil fuels that were locked in the sedimentary rocks over five hundred million years, and this combustion is measurably increasing the atmospheric carbon dioxide.”

Pp. 113. “...carbon dioxide is nearly transparent to visible light, but it is a strong absorber and back radiator of infrared radiation, particularly in the wavelengths from 12 to 18 microns; consequently, an increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide could act, much like the glass in a greenhouse, to raise the temperature of the lower air.”

Pp. 127. “The climatic changes that may be produced by the increased CO2 content could be deleterious from the point of view of human beings.”

Last updated: October 10, 2024