Last updated: January 24, 2024

Article

Allan Rohan Crite: The Artist in the Shipyard

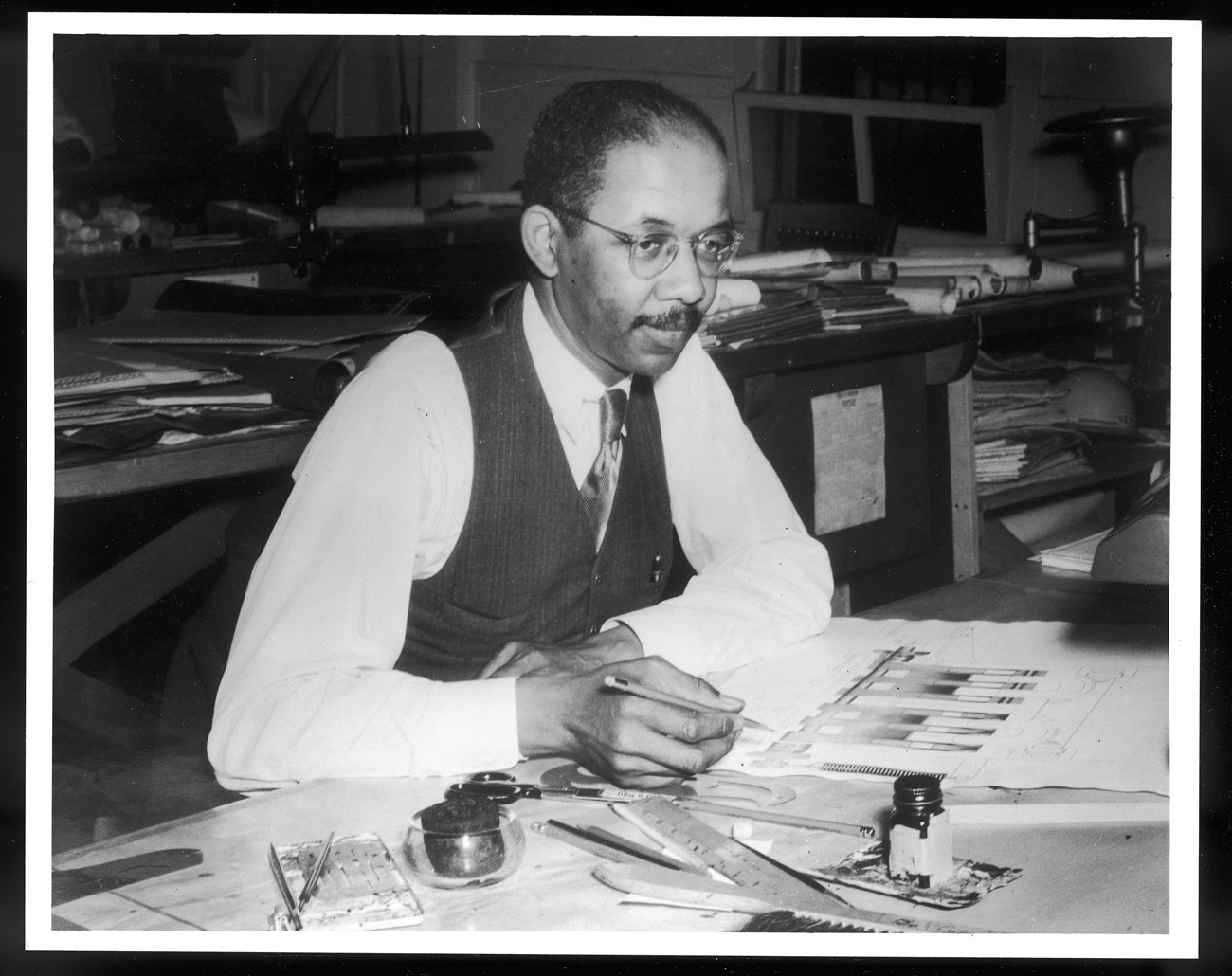

Boston National Historical Park (BNHP), BOST 7100.

"In the Drafting Room," Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum.

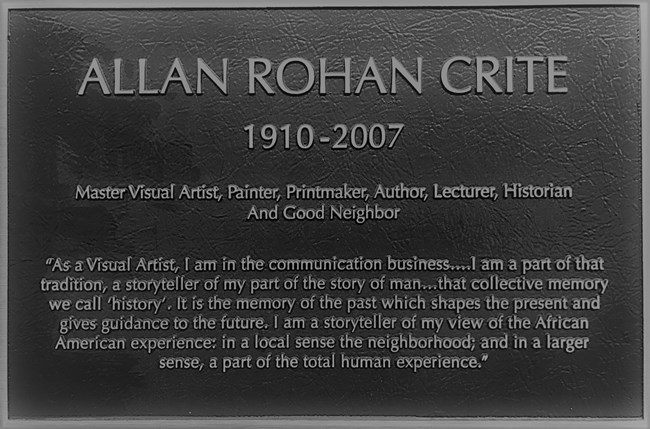

Allan Rohan Crite was an extraordinary employee at the Charlestown Navy Yard during World War II and the post-war years. Crite worked as an Engineering Draftsman and Technical Illustrator in ship design for over thirty years, and at the same time he pursued his passions for art and for religion. Art historian Regenia A. Perry called him "an artist with few peers among his generation."[1] He also served his community as a pastoral leader in the Episcopal church.

Born in 1910 in Plainfield, New Jersey, Allan Rohan Crite was the only child of a middle-class family. His family moved that same year when Crite's father, Oscar Crite, took an engineering job in Boston. Allan Crite lived most of his life in Lower Roxbury/South End, an ethnically-diverse neighborhood of Boston.

Over the years, Crite has shared his life experiences through oral histories. In these oral histories, including one documented by Boston National Historical Park, Crite is engaging, congenial, and humorous.[2] He often enjoyed talking with others about his art and faith, in addition to his work at the Navy Yard.

His Art

By the time Crite turned six years old, his mother and his teachers had already been encouraging his interest in art. At age sixteen he won his first prize for drawing. He was never without a sketch pad. "When he wasn't eating, he was drawing"[3] said his mother Annamae about Allan's early years. After graduating high school, he attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston on a scholarship.

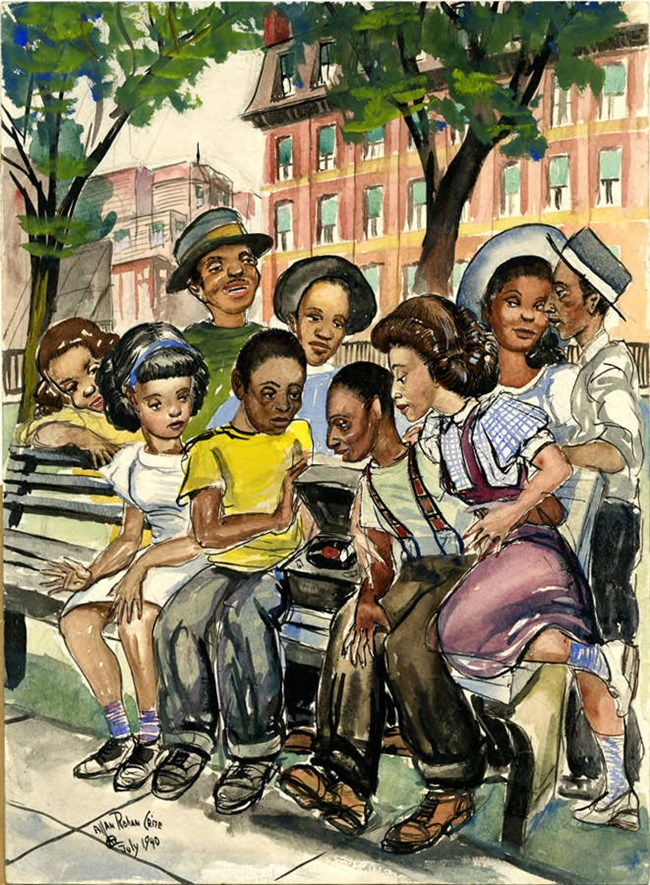

"A Course in Music Appreciation," July 1940, Courtesy of Boston Athenaeum.

In 1929 at age nineteen, Crite received his first public recognition in an exhibition of his work. He graduated from the Museum School in 1936 and participated in the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). This New Deal program aided artists while an economic depression continued in the US in the 1930s. Crite produced numerous paintings during the few years he participated in the WPA. These works became government property, and some are in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

Crite said the main goal of his art was to depict African Americans leading ordinary lives. He painted over 35 street scenes from around his neighborhood, and they became his best-known works. Crite expressed his massive imagination in a vast body of artwork over his lifetime, using oil paint, watercolors, ink brush, lithographs, linoleum blocks and graphite.

He often donated his artwork; the Boston Athenaeum likely holds the largest number of his works, over seventy items, all donated by Crite. For nearly eighty years, he regularly exhibited his artwork throughout the U.S. Boston newspapers frequently and favorably reported on his career.

"[Streetcar madonna]," 1946. Courtesy of Boston Athenaeum.

His Faith

Crite called himself a "liturgical artist" and in the early 1940s, Harvard University Press published two of his books illustrating African American Spirituals. He became "the best-known artist in the Episcopal Church."[4]

During 1948-1950, the well-known Rambush Decorating Company of New York hired Crite to create artwork for church interiors. One was a mural for St. Augustine’s Church in Brooklyn, New York. This mural covered 345 square feet, the largest single artwork Crite ever created; unfortunately, a fire destroyed it in 1972. Crite completed two lesser church projects for the Rambush firm in Detroit and Washington, DC.

As a pastoral leader, Crite lectured on religious art at Episcopal churches around the US. For over 30 years starting in 1955, he also created, printed, and mailed over 1200 monthly church bulletins to many parishes all done at his own expense. His last published book was a religious work of fifteen engravings, The Revelation of Saint John the Devine published in 1995.

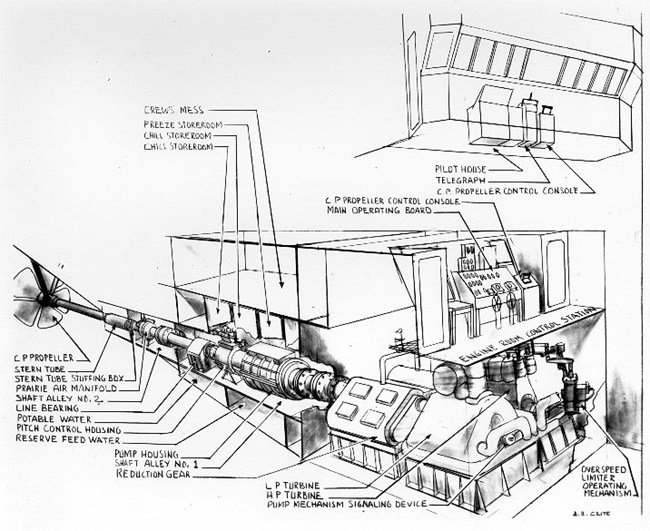

BNHP BOST 13879

His Job

In the late 1930s, Crite turned to public-service work to make a living. He held a job with the US Coast and Geodetic Survey as a mapmaker for about a year, and then he worked at the Charlestown Navy Yard, then known as the Boston Naval Shipyard.

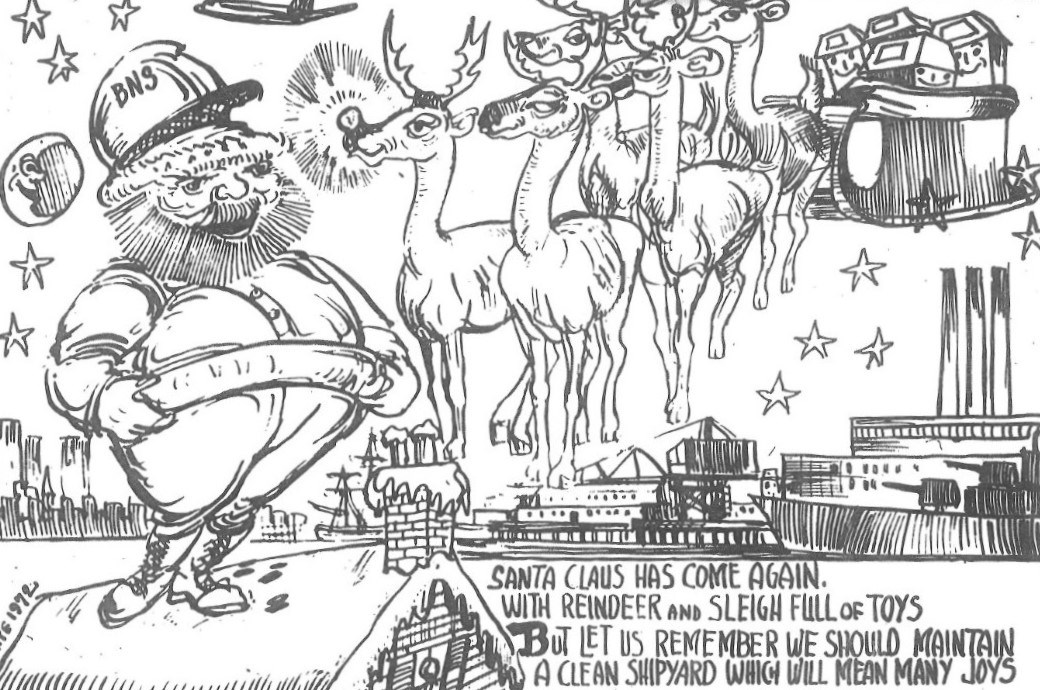

Crite worked at the Shipyard from 1941 to 1974. He made detailed drawings and illustrations of the propulsion systems that moved ships across oceans. His unique perspective drawings made it easier for US Navy shipbuilders to visualize new designs. "I was the only one in the Yard who did this kind of work" Crite later recalled.[5] He also made numerous drawings for both The Shipyard News, the Yard's newspaper, and for public-service signs used in the Yard. The Shipyard News also regularly reported on Crite's accomplishments outside the workplace.

BNHP

BNHP, BOST 7646-1.

After WWII with fewer ships needed in peacetime, the US Navy laid off many workers, including Crite three times, some periods lasting a year. It was during these furloughs when Crite created artwork for church interiors for the Rambush Company.

While employed in the Yard, Crite attended night school for fourteen years at the Harvard Extension School and earned a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Extension Studies in 1968. His co-workers in the Design Department gave him a "Harvard chair," a traditional gift given to Harvard graduates.

Although racial discrimination at the Boston Naval Shipyard was known, Crite said in a 1984 Boston Globe newspaper interview that "I was highly respected, I think. They knew my religious work and so they had quite a respect for that; they sort of regarded me as just somebody around who just happened to be black."[6]

When the Charlestown Navy Yard closed permanently in 1974, Crite became semi-retired and worked part-time as a librarian at the Grossman Library at Harvard University.

BNHP, BOST 13344-5

NPS Photo/Parrow

His Legacy

Crite's artistic talents made a lasting impact on his community. Elma Lewis, founder and director of the National Center of Afro-American Artists through the 1990s, recognized Crite's astounding contributions to his field. Reflecting on Crite's art in the 1930s and 40s, Lewis said, "At a time when very few people were celebrating the black community, Crite was doing that."[7] Crite also mentored other artists who called him the Dean of African American artists in New England.[8]

Crite received numerous distinctive awards, including the Commonwealth Award from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the Harvard University Centennial Medal. He also received honorary doctorates from four schools. Over 100 institutions have collections of his work. In 1986, the City of Boston dedicated the Allan Rohan Crite Park on Columbus Avenue nearby his former home.

Crite married Jackie Cox in 1986 and she has devoted herself to cataloguing and preserving the thousands of items that Crite created. She has helped to organize many retrospective exhibitions of her husband's work.

In 2003, the staff of the Boston National Historical Park held an exhibition in the park's visitor center featuring items from Crite's long career at the Boston Naval Shipyard. Crite was able to attend this exhibit at age 93; he died in 2007.

Allan Rohan Crite was an extremely versatile, productive, generous, and religious artist. Boston National Historical Park, part of the National Parks of Boston, is honored to share the story of this Engineering Draftsman and Technical Illustrator at the Boston Naval Shipyard.

Footnotes

[1] Regenia A. Perry, "Free Within Ourselves: African American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art" (Washington, DC: Pomegranate Art Books, 1992), 51-53.

[2] Robert Brown, "Oral History Interview with Allan Rohan Crite, January 16, 1979- October 22, 1980," Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. https://www.aaa.si.edu/download_pdf_transcript/ajax?record_id=edanmdm-AAADCD_oh_212600 (accessed November 26, 2022); Julieanna L. Richardson, and Paul Bieschke (videographer), Interview with Allan Crite, February 12, 2001, The Historymakers, https://da.thehistorymakers.org/storiesForBio;ID=A2001.018 (accessed December 23, 2022).

[3] Edward Clark, “Annamae Palmer Crite and Allan Rohan Crite: Mother and Artist Son—An Interview”, MELUS, Non-traditional Genres, Vol. 6, No. 4 Winter 1979, pp. 67-78, Oxford University Press.https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.bpl.org/stable/467058#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[4] Mark Feeney, "Allan Rohan Crite, 97, Dean of N.E. African American Artists," Boston Globe, September 8, 2007, p. C9.

[5] Dan Yaeger, "The Charlestown Navy Yard: An Oral History," Boston Globe, December 2, 1984, SM 12.

[6] Yaeger, "The Charlestown Navy Yard: An Oral History," SM 12.

[7] Jeff Kantrowitz, "Allan Rohan Crite: Portrait of Artist as City Man," Boston Globe, February 28, 1993, 233.

[8] National Center of Afro-American Artists, "Allan Rohan Crite," https://ncaaa.org/the-museum/collections-exhibitions/alan-crite/ (accessed November 26, 2022).

Sources

Carlson, Stephen P. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Vol 3. Boston, MA: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010.

Giuliano, Charles. "Words & Images Allan Rohan Crite 1910-2007, A Virtual Visit to St. Botolph Club Exhibition, April 8, 2020," Berkshire Fine Arts, https://www.berkshirefinearts.com/04-08-2020_words-and-images-allan-rohan-crite-1910-2007.htm (accessed November 26, 2022).

Guerra, Cristela. "Jackie Cox-Crite and Cristela Guerra in the Neighborhood: A Celebration of Allan Rohan Crite," Boston Athenaeum, April 2021, https://vimeo.com/543597745 (accessed November 26, 2022).

Mays, Andrea L. "Revisioning Reality: Normative Resistance in the Cultural Works of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Nella Larsen, and Allan Rohan Crite, 1915-1945." (2014), p. 93-126. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=amst_etds (accessed November 26, 2022).

Slautterback, Catharina. "Allan Rohan Crite Drawings and Watercolors," Boston Athenaeum Digital Collections, https://cdm.bostonathenaeum.org/digital/collection/p16057coll31 (accessed December 26, 2022).