Last updated: January 31, 2025

Article

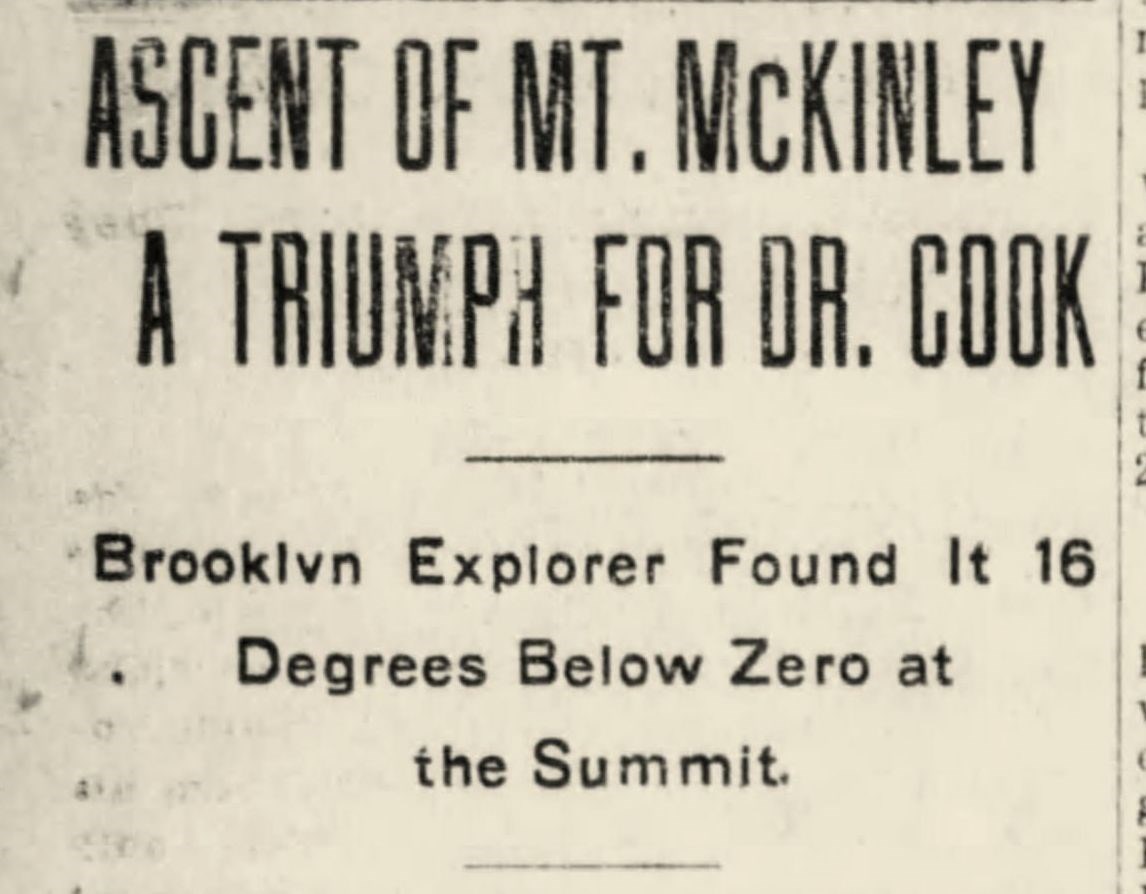

The Ruth of the Ruth Glacier

R-U-T-H Doesn't Quite Spell TRUTH

By Erik Johnson, Denali Historian

William C Clark, esq.

Photo published in the Standard Union (Brooklyn) on July 26, 1903.

During his exploration of the Denali region in 1903, Cook named the largest glacier for his stepdaughter Ruth Hunt. Ruth would have been about four years old at the time but little is known about the rest of her life. She was born around 1899 and legally adopted by Cook after he married her mother Marie Fidele Hunt in 1902.[3] Ruth eventually married and became Ruth Hamilton. She had a son, and a daughter named Bette who allegedly visited Denali in 2006 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her grandfather's ascent. Ruth died in 1970 and was buried at the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York—the same final resting place as her father.[4]

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

[2] News of Cook's summit was published by the press but almost immediately met with skepticism from people in his own climbing party (Professor Herschel Parker and Belmore Browne among the skeptics). Cook's summit claim faced increased scrutiny after he also claimed to be the first person to reach the North Pole in 1908. Cook spent the rest of his life defending his accomplishments but there were extensive efforts to debunk them. He lost much credibility when he was sentenced to prison for mail fraud in the 1920s. There has been a group dedicated to Cook’s defense, and there continues to be defenders over a century later. The NPS acknowledges the 1913 Karstens-Harper-Tatum-Stuck expedition as the first recorded summit.

[3] After Cook circumnavigated Mount McKinley in 1903, he wrote an article for the American Geographical Society in 1904 called "Round Mount McKinley. In the article he describes "Ruth Glacier" (named for his daughter) and "Fidele Glacier" (named for his wife at the time). Fidele Glacier was officially named "Eldridge Glacier" in 1913. Cook also states that he named the glacier for Ruth in his book To the Top of the Continent.

[4] Ruth had a younger stepsister, Helene Cook Vetter, who spent much of her life defending her father’s honor.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division