Last updated: July 28, 2021

Article

Exploring & Cataloging Denali's Microwilderness

By Jessica Rykken, Entomologist

Ryan O’Donnell CC BY-NC-ND

NPS Photo / Jacob W. Frank

A single species, or group of species, can have significant impacts on an ecosystem. For example, spruce bark beetle outbreaks can kill off vast swaths of spruce trees in the boreal forest, with long term consequences for many forest inhabitants. Another iconic plant in the park, blueberry, relies on bumble bees for most of its pollination. Denali grizzly bears feast on blueberries in the fall to fatten up for their long winter hibernation, so bumble bees are critical for the survival of hungry bears (and humans!).

Solomon Hendrix CC By-NC

NPS Photo / J. Rykken

For example, five species of bumble bees (out of 17 species in the park) occur almost exclusively in alpine tundra. This group of bees are true Arctic and high elevation species, well-adapted to the harsh climate of these extreme environments. Forest specialists include several rove beetles and dwarf spiders that prey on insects in logs and moss. As climate change causes trees and shrubs to move upslope in Denali, will these arthropod specialists follow their shifting habitats up the mountain? Will tundra specialists decline in number as shrubs encroach into their habitat from below and there is nothing but rock and ice above? These are the kinds of questions we hope to answer in the future.

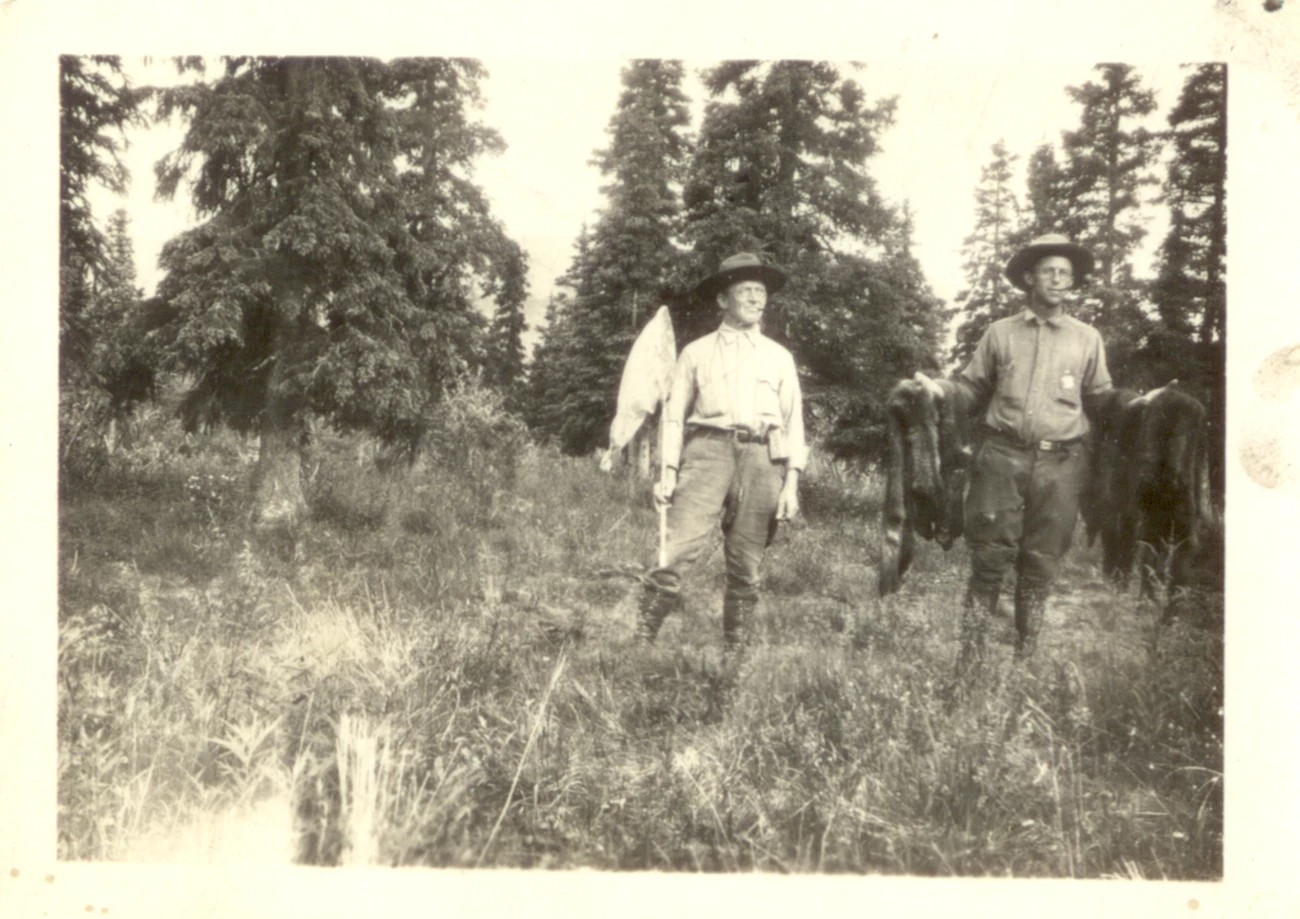

Swisher family collection No. 33. Courtesy of the Swisher family and used with permission

Nick Block CC BY

Although our recent projects are documenting hundreds of new arthropod species in Denali for the first time, the history of insect collecting and discovery in the park goes back nearly a century. For example, Frank Morand collected some of the first known specimens of the lively clouded sulphur butterfly (Colias philodice vitabunda) in Denali in 1930. In 1924, H.C. Fall discovered a new species of minute brown scavenger beetle (Corticaria arctophila) in the park. These tiny beetles feed on microfungi. Almost one hundred years later, we collected a single individual of this beetle in a shrubby thicket at mid-elevations on Mount Healy, the first time it had been documented since the original discovery!

Adam Haberski

Tiny spruce bark beetles can have a huge impact on boreal forests

Recently, we updated the National Park Service species database (NPSpecies) with all the records stored in the museum, resulting in an impressive list of almost 800 invertebrate species known from Denali! In comparison, only 199 terrestrial vertebrate species (mammals, birds, and one frog) are listed for the park. Among the 791 invertebrates, spiders and beetles made up more than half the species; flies, wasps, bees, and butterflies composed most of the remainder.

While Denali sets a great example among national parks in exploring and documenting its microwilderness, one thing is for certain: there are many, many more discoveries to be made!

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service