Last updated: May 24, 2023

Article

Discover Touro Synagogue: Lightning Lesson from Teaching with Historic Places

Touro Synagogue stands today as the oldest synagogue in the U.S. The structure was built in 1763 by the Jewish community of Newport, Rhode Island. Jewish immigrants arrived as early as 1658, attracted to the opportunities Newport provided as a major port for early American trade. Rhode Island’s commitment to religious freedom also meant that residents of all faiths could live and work together. Members of the Jewish community served as merchants, shippers, craftsmen, and producers who ultimately contributed to the town’s vibrant civic life and commercial success, and as a symbol of the nation’s tradition of tolerance and community.

About This Lesson

"Discover Touro Synagogue: A Lighting Lesson from Teaching with Historic Places," is based on the its National Register of Historic Places nomination for Touro Synagogue. Andrea Ledesma, a digital historian and National Council for Preservation Education (NCPE) intern, wrote this lesson with editing assistance from National Park Service Historian Katie Orr; Tammy Boyd, Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park; and the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education staff in Washington, D.C. This lesson is one of a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Objectives

1. Describe the establishment of interfaith communities in Colonial U.S. and how their formation contributed to principles of religious freedom.

2. Locate places of worship and explain how they shape civic and social life.

3. Identify and investigate connections between historical events and contemporary issues.

Materials for Students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer, projected on the wall, or printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students.

1. Map of Newport, Rhode Island in 1777, showing the location of places of worship across the town;

2. Primary source reading of a letter from Moses Seixas, President of Congregation Yeshuat Israel, to President George Washington;

3. Primary source reading of a letter from President George Washington to Moses Seixas;

4. Photograph of the exterior of Touro Synagogue;

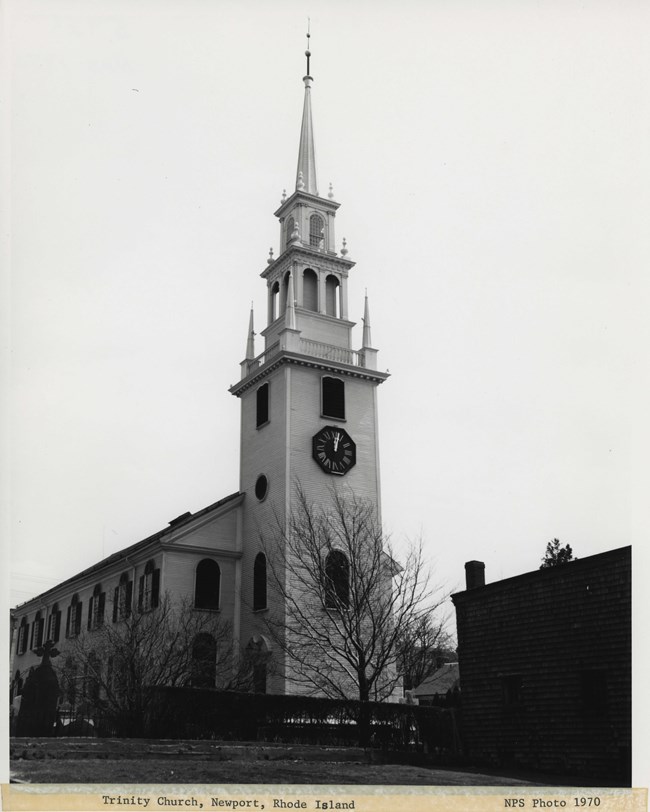

5. Photograph of the exterior of Trinity Church;

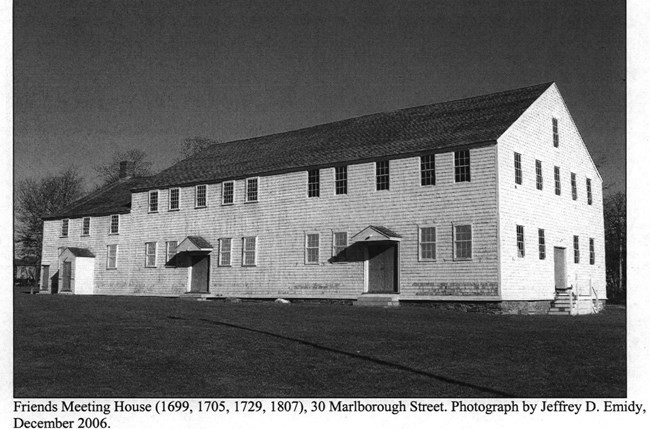

6. Photograph of the exterior of the Friends Meeting House.

Visiting the Site

Touro Synagogue was declared a National Historic Site in 1946. The synagogue is owned by the Congregation of Shearith Israel of New York City and privately operated by the Touro Synagogue Foundation. Touro Synagogue is located at 85 Touro St, Newport, RI 02840. Visiting hours vary according to worship services, as well as Jewish holidays, ceremonial occasions and special events. To learn more, visit the synagogue’s website.

Where This Lesson Fits into the Curriculum

Time Period: 19th century to the present

Topics: This lesson can be used in history and social studies curricula to cover topics related to religion, civics, colonial history, and the early American republic.

Relevant United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

This lesson relates to the following National Standards for History from the UCLA National Center for History in the Schools:

US History Era 2

• Standard 2: How political, religious, and social institutions emerged in the English colonies

Relevant Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

This lesson relates to the following Curriculum Standards for Social Studies from the National Council for the Social Studies:

• Theme I: Culture - Standard C, E

• Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change - Standards B, F

• Theme III: People, Places, and Environments - Standards B, G

• Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity - Standards A, B, F

• Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions - Standards A, E

• Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance - Standard D

• Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices - Standards A, B

Relevant Common Core Standards

This lesson relates to the following Common Core English and Language Arts Standards for History and Social Studies for middle and high school students:

Key Ideas and Details

• CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

• CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

Craft and Structure

• CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6: Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author's point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

• CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7: Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

Getting Started

- How many different religions can you name?

- How many of those religions do you think were present in colonial America?

- What historic place might you study to answer these questions? Why?

American Revolution and Its Era: Maps and Charts of North America and the West Indies, 1750 to 1789, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

Map 1: A Plan of the town of Newport in Rhode Island, 1777

Map Key

A. Trinity Church

B. Congregational Meeting House

D. Baptist Meeting House

H. Friends Meeting House

K. Jews Synagogue

This map illustrates Newport, Rhode Island as it stood in the late eighteenth century. The town was a major port in early American history. Ships carried everything from chocolate and textiles to rum and enslaved people. Many traders were Jewish immigrants who benefited from their knowledge of commerce and enterprise. These businesses helped make Newport one of the largest and wealthiest settlements in Rhode Island.

Questions for Map 1

1) Where is Touro Synagogue? Where else did Newport residents go to practice their religion? Describe where these places were located in relation to each other.

2) What kinds of businesses would you expect to find in a port town, a town built around shipping and oceanic trade? How might religion influence business practices? (Hint: Did any religion(s) prohibit dealing in certain types of food, alcohol, enslaved people, etc.?)

3) Do you think being good traders and merchants helped Jewish immigrants integrate into Newport? Why or why not?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: “Moses Seixas' Letter from Congregation Yeshuat Israel”

Sir,

Permit the children of the stock of Abraham to approach you with the most cordial affection and esteem for your person and merits―and to join with our fellow citizens in welcoming you to Newport.

With pleasure we reflect on those days―those days of difficulty, and danger, when the God of Israel, who delivered David from the peril of the sword―shielded Your head in the day of battle: and we rejoice to think, that the same Spirit, who rested in the Bosom of the greatly beloved Daniel enabling him to preside over the Provinces of the Babylonish Empire, rests and ever will rest, upon you, enabling you to discharge the arduous duties of Chief Magistrate in these States.

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People―a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance―but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine:

This so ample and extensive Federal Union whose basis is Philanthropy, Mutual confidence and Public Virtue, we cannot but acknowledge to be the work of the Great God, who ruleth in the Armies of Heaven, and among the Inhabitants of the Earth, doing whatever seemeth him good.

For all these Blessings of civil and religious liberty which we enjoy under an equal benign administration, we desire to send up our thanks to the Ancient of Days, the great preserver of Men beseeching him, that the Angel who conducted our forefathers through the wilderness into the promised Land, may graciously conduct you through all the difficulties and dangers of this mortal life: And, when, like Joshua full of days and full of honour, you are gathered to your Fathers, may you be admitted into the Heavenly Paradise to partake of the water of life, and the tree of immortality.

Done and Signed by order of the Hebrew Congregation in NewPort, Rhode Island August 17th 1790.

Moses Seixas, Warden

(Source: Seixas, Moses. Touro Synagogue Foundation.)

Reading 2: “George Washington’s Letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport”

Gentlemen:

While I received with much satisfaction your address replete with expressions of esteem, I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you that I shall always retain grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced on my visit to Newport from all classes of citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security.

If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy—a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity.

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants—while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

G. Washington

(Source: Washington, George. Touro Synagogue Foundation.)

Questions for Determining the Facts

1) Who was Moses Seixas? Who did he write this letter to and why?

2) Recall this passage from Reading 1: "a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance―but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine."

In your own words, summarize what Seixas meant by those lines. What might he have wanted for himself and the people at Touro? What evidence supports your answer?

3) In his reply, did Washington agree or disagree with Sexias? What do you think Washington meant by “while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid”?

Photo 1: Touro Synagogue, exterior, undated.

Touro Synagogue was built in 1763 with funding provided by the Jewish communities in Newport, Rhode Island, as well as Jewish communities overseas in London, Jamaica, and Suriname. The building was designed by Peter Harrison, a British sea captain, merchant, and self-taught architect. His designs for Touro Synagogue, as well as other places of worship in New England, are celebrated for bringing European architecture to the American colonies. The building is named after Isaac Touro, the man who watched over the synagogue and its congregation. A formal dedication ceremony was held during the second night of Hanukkah in 1763.

Trinity Church was built in 1726 with the steeple spire constructed in 1741. The congregation was originally Anglican, Huguenot, and Quaker; today it is an Episcopalian church.

Photo 3: Friends Meeting House, exterior, 2006.

The Great Friends Meeting House was built in 1699 and is the oldest surviving house of worship in Rhode Island. It was built by Quakers, who were widely known for their plain style of living and pacifism (opposition to war or violence). Their beliefs, including condemning violence against Native Americans, were a threat to the English crown and they were frequently driven out of colonies. Rhode Island was one place where they could live their beliefs in peace.

Questions for Visual Evidence

1. Briefly describe Touro Synagogue, Trinity Church, and the Friends Meeting House. How are they alike? How are they different?

2. Do any of these buildings look like a house of worship to you? Why or why not?

3. Why do you think these buildings look the way they do? (Consider things like the time in which they were built, available building materials, how much money the congregations had, etc., as well as religious beliefs and expressions of those beliefs.)

Activities

Have students discuss the constitutionality of prayer in schools in the classroom. The activity can be a brief pro-con debate for younger children (a short summary of the case as well as suggested discussion topics can be found at https://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/facts-and-case-summary-engel-v-vitale) or older students can recreate the Supreme Court case with justices, plaintiffs, and defendants. Those students not involved in litigating can argue for either side by presenting amicus curiae (“friends of the court”) briefings to the court. A list of briefings presented in the Engel v. Vitale Supreme Court case (see Optional Activity 1, below) can be found at https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/370/421.html.

For students or teachers interested in exploring the Establishment Clause, there have been numerous other cases heard in the Supreme Court. The most frequently cited are:

- Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) – government actions in violation of the Establishment Clause

- Wallace v. Jaffee (1985) – voluntary silent prayer

- Lee v. Weisman (1992) – prayer in the special context of a graduation ceremony

- Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000) – allowing students to speak over the PA system before sporting events

For students or teachers interested in exploring the Free Exercise Clause, there are also a number of Supreme Court cases. They include:

- Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) – compulsory secondary education for Amish children

- Widmar v. Vincent (1981) – University of Missouri refusing to allow a registered student religious group to conduct meetings in school facilities

- Westside Community Board of Education v. Mergens (1990) – group of students wanting to start a Christian Bible study group

- Rosenberger v. University of Virginia (1995) – funding secular student publications but withholding similar funds from religious student publications

There are many other contemporary issues around freedom of religion that students can explore. They include:

- Wearing a veil or other face covering in photos for government-issued identification cards (such as Muslim women who wears burkas or niqabs),

- Refusing to vaccinate children because of religious beliefs (anti-vaxxers), and

- Businesses refusing service to employees or customers based on religious beliefs (such as Hobby Lobby refusing to pay for contraception or the baker in Colorado that refused to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple).

As an extension for older or more advanced students, in addition to religious freedom, they can examine the interaction between religion and economy, religion and security, religion and public health, etc.

Optional Activity 1: Engel v. Vitale Case

According to the Bill of Rights, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” When we talk about freedom of religion, we are actually discussing two separate issues: the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. The Establishment Clause prevents Congress from establishing any religion as a state religion. The Free Exercise Clause allows any American citizen to exercise their religious beliefs, whatever they might be, as long as doing so does not violate “public morals” or a “compelling” governmental interest.

Throughout much of American history, prayer was a part of schooling. Well into the 20th century, many state laws protected or required prayer in schools. New York State had a law requiring students to start each school day with the Pledge of Allegiance (which contains the phrase, “one nation, under God”) and a nondenominational prayer that required students to recognize their dependence on God. The law let students opt out of participating if they found the activity objectionable.

In the late 1950s, a group of families led by Steven I. Engel (a Jewish man) sued the school board president, William J. Vitale, Jr., stating the practice contradicted their religious beliefs and was unconstitutional. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court in 1962. The justices decided, in a 6-1 vote (with two abstentions), that school-sponsored prayer violated the Establishment Clause. The justices went on to state that the ruling did not mean that prayer was banned from schools. Students may pray at school on their own time, but school personnel and/or state officials may not lead a prayer.

Today prayer in school is still a divisive topic. Many schools and students continue to struggle with activities such as a prayer before a sporting event or having a member of the clergy speak at a graduation ceremony.

Optional Activity 2: Executive Order 13780

On March 16, 2017 President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 13780 (Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States). The order states “the Secretary of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Attorney General, has determined that a small number of countries — out of nearly 200 evaluated — remain deficient at this time with respect to their identity-management and information-sharing capabilities, protocols, and practices. In some cases, these countries also have a significant terrorist presence within their territory.” Eight countries – Chad, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen, and Somalia – were included in the ban.

This executive order was challenged in court by numerous state governments and other organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union, eventually being heard by the Supreme Court and upheld by a 5-4 vote. The American Jewish Committee, the Zionist Organization, the Interfaith Coalition, Episcopal Bishops, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the Muslim Justice League, and numerous other religious and civic organizations wrote amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefings in support of the organizations challenging the Executive Order.

Executive Order 13780 is commonly known as the Muslim Ban. The first version of this Executive Order was Executive Order 13769. It suspended entry into the United States for citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Sudan, Somalia, and Yemen, all of which are Muslim-majority countries. Of the eight countries listed in Executive Order 13780, only North Korea and Venezuela are not Muslim-majority countries. They, along with Chad, were added in September 2017 by Presidential Proclamation 9645. The Presidential Proclamation also removed Sudan from the list.

Americans still argue about this executive order today. Some claim that it is vital to national security, and any nation with deficient security protocols should be treated as suspect, especially with the global rise of terrorism. (All four countries identified by the CIA as state sponsors of terrorism are included in the ban.) Others claim that the reason for this order is not security, but racism and religious discrimination, and point to numerous public statements and social media positings by the President as evidence.

Students can study the history of this executive order, incorporating a number of activities:

- Individual students and/or groups can write a paper or give a class presentation on how Executive Order 13780 was created.

- A class can recreate one of the court cases surrounding this order.

- Students can compare this executive order to earlier pieces of legislation, such as the Immigration Act of 1924.

- Students can pick one of the banned countries and study them in depth.

- Students can compare President Trump’s remarks to politicians in Europe who agree with him on this topic (like Geertz Wilders from the Netherlands or Marie Le Pen in France) and/or who disagree with him (like Angela Merkel of Germany or Stefan Lofven of Sweden).

Many people have drawn parallels between the Muslim Ban and Japanese American internment during World War II. Have students compare Trump’s Executive Order 13780 to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 (Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas). They can also compare the Supreme Court cases for both executive orders, Trump v. Hawaii and Korematsu v. U.S.

Another common comparison in the media that students can examine is the comparison of the Muslim Ban and the Jewish Refugee Crisis during World War II.

As an extension activity or for more advanced students, have students place the travel ban within any one of a number of broader contexts:

- Students can visit the World Bank’s Net Migration Data page or read the United Nation’s International Migration Report to better understand global human movements.

- Students can visit the United Nation’s High Council on Refugees webpage and learn about refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people. There are currently refugee crises in Syria and Yemen, among other places.

- Students can compare the travel ban to recent immigrant detentions along the southern United States border.

- Students can compare the United States to other countries that have recently started implementing immigration/refugee quotas and/or closing their borders to groups of people, especially in response to the European Migration Crisis.

References and Contributing Resources

Barry, M. John. “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea.” Smithsonian Magazine. January 2012.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, and Peter Harrison. Touro Synagogue, Congregation Jeshuat Israel, 85 Touro Street, Newport, Newport County, RI. Newport Newport County Rhode Island, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. (Accessed July 4, 2017).

Hühner, Leon. The Jews of Newport.

National Register of Historic Places, Touro Synagogue, Newport, Rhode Island, National Register, #66000927.

Office of the Vice President. Remarks of the Vice President at the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Synagogue Council of America, Touro Synagogue, Newport, Rhode Island. 1976.

Seixas, Moses. “Moses Seixas' Letter from Congregation Yeshuat Israel.” Touro Synagogue.

Touro Synagogue. “Origins.”

United States Courts. “First Amendment and Religion.”

Washington, George. “George Washington’s Letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport.”

Additional Online Resources

The websites listed below provide learners with additional information about the history of religious freedom and Touro Synagogue.

Touro Synagogue

The Touro Synagogue Foundation manages the Touro Synagogue National Historic Site in partnership with the National Park Service. The site is open to the public for regular services and guided tours. The tour schedule may vary due to Jewish holidays, ceremonial occasions and special events. Visitors can also enjoy exhibitions at the Loeb Visitors Center next door.

Visit the synagogue’s website to learn more about the history of the site, its congregation, and the greater Jewish community of Early America.

National Archives and Records Administration

2016 marked the 225th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights. The National Archives commemorated the milestone with exhibit and educational resources, including this downloadable workbook, “Putting the Bill of Rights to the Test: A Primary Source-Based Workbook” compiles a number of primary sources for students to study the principles and protections of the Bill of Rights and explore how these have changed throughout American History. Each chapter provides background information, key questions, primary sources, and discussion questions.

Center for Jewish History

The Center for Jewish History’s online catalog provides access to documents, images, video, and other primary and secondary sources related to Jewish history. Users can search across collections from partner organizations, including the American Jewish Historical Society, Yeshiva University Museum, and Yivo Institute for Jewish Research. The site aims to be a central hub for centuries of Jewish history, culture, and art.

Library of Congress

Religion and the Founding of the American Republic is an online exhibition by the Library of Congress. Drawing from manuscripts, photographs, books, and other materials, the exhibition maps how the pursuit and establishment of religious freedom runs through U.S. history. The story begins in the 1600s, with the pious men and women crossing the Atlantic Ocean to America, and ends with the religious awakenings of the New Republic in the 1800s.

National Constitution Center

The National Constitution Center maintain an online interactive edition of the U.S. Constitution, including the First Amendment. The site features not only transcripts from the primary source document, but also essays that explore the challenges to and transformations of the Constitution over time. Authors of these essays include scholars of history, law, and civil liberties.

Tags

- teaching with historic places

- jewish history

- rhode island

- rhode island history

- civics

- colonial

- migration and immigration

- national register of historic places

- national historic landmark

- historic preservation

- historic preservation education

- colonial america

- religion

- religious history

- constitution

- bill of rights

- constitution history

- twhp

- american independence

- twhplp

Success

Thank you. Your feedback has been received.

Error

alert message