Last updated: February 28, 2025

Article

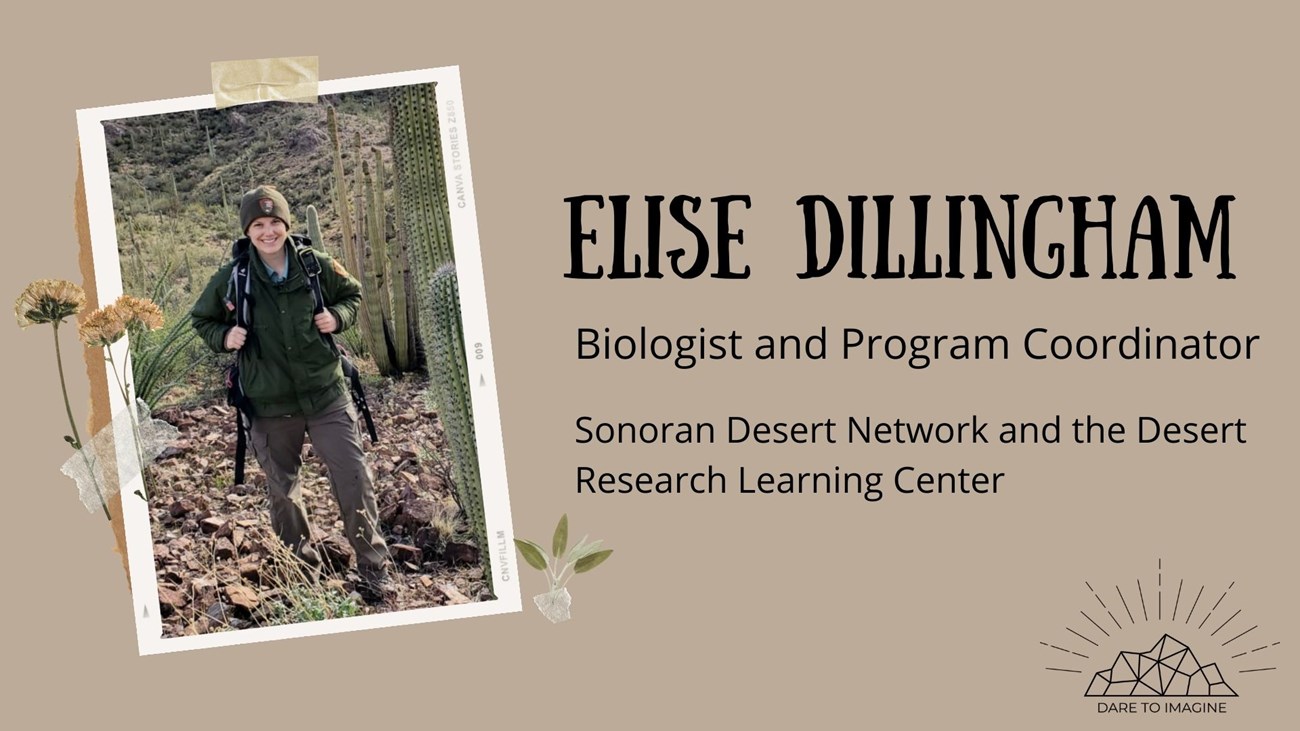

Dare to Imagine: Elise Dillingham

Women Lifting Other Women

Elise is SO dedicated to her work with the NPS. She runs the Desert Research Learning Center (DRLC), as well as spearheading a new mammal monitoring protocol, using game cameras. She takes on new tasks as needed and has the chops to do them well, all while guiding the DRLC logistics and programming.

-Sharlot Hart, Archeologist, Southern Arizona Office

Elise, what project or work would you like to highlight?

I would like to highlight our terrestrial mammal monitoring program that engages youth citizen scientists through our EcoMonitoring Corps (EMC).

Will you tell us a little about that project?

The EcoMonitoring Corps (EMC) is a citizen science internship program operated through the Sonoran Desert Network. It unites students and young professionals with National Park Service (NPS) scientists in support of mammal monitoring at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Saguaro National Park, and Chiricahua National Monument. Terrestrial mammals in these parks face many challenges, including climate change and myriad impacts from increased border-related human activities and infrastructure. We use wildlife cameras and occupancy modeling to monitor mid-sized terrestrial mammals and assess those impacts. Our goal is to track biologically significant changes at the community and population levels. Using motion-triggered cameras, we can monitor which animals are occupying given areas. This helps us investigate, for instance, whether mule deer migration patterns are changing, if the prevalence of carnivores is shifting, or whether changes in one trophic level appear to impact another. Knowing about trends like these allows park managers to study their underlying causes leading to more effective management and conservation strategies. The monitoring requires a considerable number of cameras to be deployed and collected in remote areas. The Sonoran Desert Network doesn’t have enough staff to do all the work, so the EcoMonitoring Corps provides vital assistance.

What was your path like? How did you get to where you are now?

At a young age, I developed a deep admiration for the natural world. But I didn’t associate it with a profession until college. I grew up in Flagstaff, Arizona. Contrary to the images “Arizona” conjures for most (scorching desert + cactus), Flagstaff is situated at 7,000 ft in the world’s largest ponderosa pine forest. It has four unique seasons, so I was able to build igloos in the winter and have water balloon fights in the summer. I grew up in a neighborhood filled with kids on the base of Mount Elden. The forest was our escape: an enchanted place to fight imaginary dragons, build forts, and learn to avoid woes like poison ivy. Many of the science classes I took in high school I unfortunately found to be dull, so I was much more interested in other subjects. It wasn’t until in college that a few professors opened up the wonders of ecology to me. As an undergraduate, I worked in a wildlife biology lab, trapping, radio-collaring, and tracking foxes, raccoons, and skunks. I ultimately majored in environmental studies and loved the multi-dimensional nature of it; how countless disciplines collide around environmental issues.After graduation, I got a job as a field instructor for an environmental education non-profit, which gave me experience working with diverse audiences. I then became an intern for the National Park Service, developing wildlife camera traps for reptiles, which ushered in career opportunities. A master’s degree in wildlife conservation biology from Colorado State University led me to the position I’m in today. I love the dynamic nature of my job and being able to have one foot in environmental education and the other in science. Working for 11 different national parks is also phenomenal.

What was the hardest part about getting to where you are now? How did you overcome it?

I struggled to figure out what to study in college, and which career path to pursue. I was originally a nursing major, training to become a flight nurse for the US Air Force. But after completing clinical rotations assisting doctors and nurses, I questioned whether to continue. Becoming a nurse was a goal I had for years. I enjoy emergency medicine, and nursing is a very sensible profession, but I didn’t feel as passionate about it as I originally thought I did. I reached a crossroad where I had to either sign a contract with the US Air Force and commit to years of service as a nurse, or quit. Making the decision was agonizing, but I ultimately decided to follow my intuition and drop out of the program.I didn’t know what to study and I felt all the work I’d put into pursuing nursing was a waste. After soul-searching, I decided to pursue environmental studies. I didn’t know what I would ultimately do, but banked on the fact that I’ve always loved the outdoors and been passionate about wildlife and environmental conservation. I’m so glad I followed my heart and made that decision. I’ve experienced marvelous places, met exceptional people, and participated in countless meaningful projects. Sometimes a blind jump is the best choice!

What are you most proud of?

A long legacy of conservationists, scientists, educators, and activists have worked tirelessly to protect the natural world and reduce human impact on it. I’m proud to be part of that community. Those of us alive today bear witness to a pivotal moment in history. Our climate is in crisis and the fate of many ecosystems and species rest in our hands. I hope that I can contribute to the preservation of our planet and the cultivation of a shared environmental ethic.Favorite Quote?