Last updated: February 16, 2024

Article

Eisenhower and Evers: Leaders in War, Leaders for Change

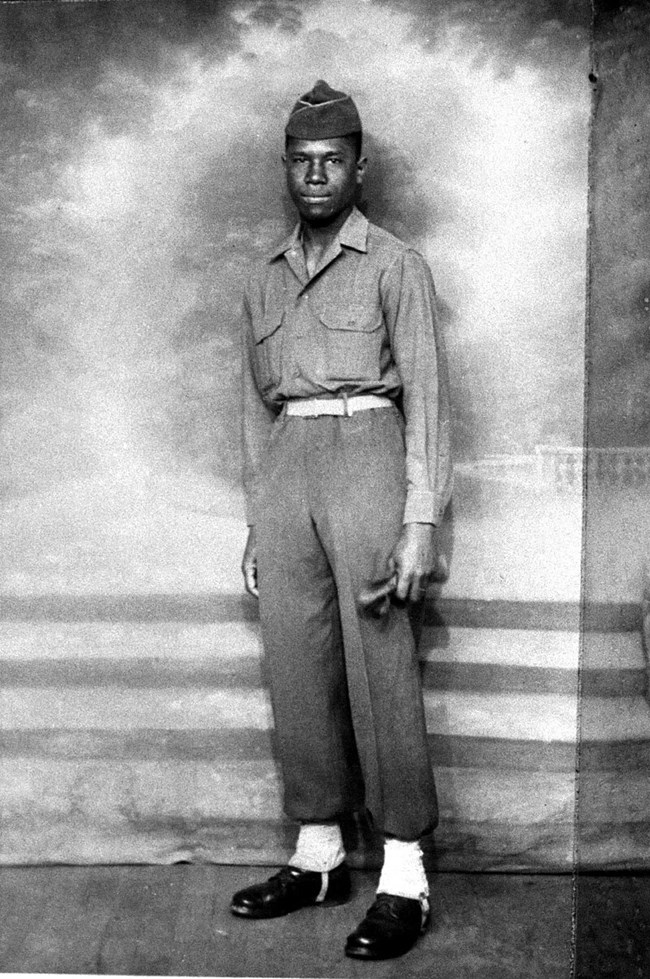

U.S. Army Photograph

During the Second World War, leaders emerged at every level of military rank and position. Many of these individuals went on to shape the United States and the world in the years after World War II. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Medgar Evers were two such Americans.

In the summer of 1944, though separated by rank, race, and status, these two men were united by a common goal—the Allied Invasion of Normandy.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, promoted to his new role at the end of 1943, was charged with planning and executing the Allied invasion of Nazi occupied Normandy, France, known as Operation Overlord. Eisenhower committed every waking moment since receiving his new command – nearly six months’ time – to analyzing, tweaking, and obsessing over the complicated logistics of what would be an unprecedented invasion of global importance. One of the general’s greatest concerns was the state of his soldiers and their readiness for the task ahead of them.

For Medgar Evers, the task of invading Normandy looked much different. A young Black man from rural Mississippi, Evers was not interested in making a career out of military service when he joined the U.S. Army in 1943. His enlistment at the age of 17 placed him in the footsteps of his older brother Charles, whom he admired. It also gave him an escape from the segregation and racism that surrounded and impacted his life and family. For Evers, enlisting was a way to serve his country, even if that service did not guarantee him equality.

During World War II, over one million African Americans served in the U.S. armed forces. While some saw combat, many Black soldiers were away from the frontlines in support roles. Their work, though often overlooked, was essential, and many became the unsung heroes of the war – without them, victory was impossible.

In June 1944, once General Eisenhower gave the command to move forward with the invasion of Normandy, after months of planning, strategizing, and agonizing over the largest amphibious invasion in history, he watched as a vast armada of soldiers, sailors, and airmen from dozens of nations went forward with what he termed the “Great Crusade.”

Among those hundreds of thousands who went forward was Medgar Evers. Though not on the front lines of combat, Evers and other African American soldiers played an invaluable role in not only the invasion of Normandy, but in the fight to liberate Normandy, France, and Europe itself.

Evers served with the segregated 325th Port Company, part of the Red Ball Express truck convoy system. Named for the red dots used to mark priority express trains in the United States, the Red Ball Express was famous for its efficient and essential supply delivery. This convoy deployed Army trucks in a nonstop loop transporting much needed resources such as gasoline, ammunition and food made it to the front lines.

The months ahead were pivotal for both Eisenhower and Evers. For Eisenhower, he led a vast Allied coalition that faced new challenges and stresses daily. For Evers, the war in Europe meant learning that life outside the United States did not always mean an escape from the segregation he experienced at home. Like many African Americans serving in World War II, Evers was still subject to racism and discrimination overseas, though primarily from white officers. Years later he wrote of becoming acquainted with a French family, noting that their kindness stayed with him for years to come and provided a stark contrast to how some of his own countrymen treated him.

After the war, both Eisenhower and Evers used their wartime experiences to influence their post-war world. For Ike, his time leading a vast Allied coalition prepared him for further leadership roles—Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, president of Columbia University, Supreme Commander of NATO Forces in Europe, and eventually, President of the United States.

For Medgar Evers, though he had fought for democracy abroad, he returned home to a country that still refused him the same rights that other citizens enjoyed. Shaped by the experiences of war, Evers was unable to stand by silently while injustices and racial inequality scarred the nation.

From 1954 to 1963, Evers served as the Mississippi field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. His team also lead investigations into violent crimes against African Americans, including the murder of Emmett Till. His unwavering work for progress was dangerous and pro-segregationists and members of white supremacy groups, threatened his life.

In 1963, after attacks on himself and his family which included a Molotov cocktail thrown at his home, Evers said “If I die, it will be for a good cause,” Once again he stood fearless in the face of hatred.

On June 12th, Evers was murdered in the carport of his family home in Jackson, Mississippi, now part of the Medgar and Merlie Evers Home National Monument.

Medgar’s wife, Myrlie, chose to have him interred at Arlington National Cemetery. While much of his work on Civil Rights took place in Mississippi, Myrlie believed that her husband’s sacrifice and legacy “belonged to everyone.” He had answered his nations call to serve in war and returned with a call to his country to truly become the champion of democracy it had claimed to be.

Dwight Eisenhower never knew the hardships and persecutions which Medgar Evers knew so well. Each had been shaped by their experience of service during World War II, and they both used that experience to fuel their post-war leadership as they shaped the country for which they had fought.

In some ways, their post-war leadership echoed their service during the war. While Eisenhower occupied the presidency, making slow progress in the arena of Civil Rights, Evers once again found himself playing a vital role doing the difficult work of advancing freedom and equality. Once again, he faced danger in the name of freedom. This time, in his post-war world, the danger came from his own countrymen.