Last updated: October 17, 2024

Article

The Castle and the Clock Tower: Understanding Industrialization Through the Gothic

Cameron, David Young, Sir. "Castle Urquhart." Print. 1929. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/g732f6664 (accessed November 21, 2023).

By Dr. Sarah Buchmeier

In 1764, the English writer Horace Walpole published his novel, The Castle of Otranto. It was a new kind of storytelling, a narrative set in the real world but filled with plot twists fueled by scary, at times even horrifying, events.

In the novel, a sickly young prince is mysteriously crushed to death by a giant helmet, which sets off a series of desperate attempts by his parents to avoid an ancient prophecy that threatens their claim to the castle. Walpole treats his readers to an array of frightening scenes—an underground church, ghostly and skeletal apparitions, and a crumbling castle.

The Castle of Otranto became a model for many books to follow, The Mysteries of Udolpho, The Italian, The Monk. Following Walpole’s lead, these writers called their narratives “Gothic” tales, and the Gothic grew into a genre or category of writing marked by gloomy settings, mysterious events, and sometimes supernatural interventions.

Public domain

Gothic writing was one literary response to the anxieties produced by a changing society at the close of the eighteenth century. Some 70 years later, as Dr. Bridget Marshall writes in her book Industrial Gothic: Workers, Exploitation and Urbanization in Transatlantic Nineteenth-Century Literature (2021), Gothic tales would become a popular reading choice among the factory workers of New England’s expanding textile mills. While part of the attraction to Gothic literature was likely the simple thrill of a scary story, Marshall argues that the Gothic environment (gloomy, mysterious, foreboding) resonated with the often horrifying conditions of work at the mills. Moreover, the Gothic’s ability to depict “the fate of the powerless against forces of both individual and institutional evil” made it a genre particularly relevant to the new era of industrial capitalism.1

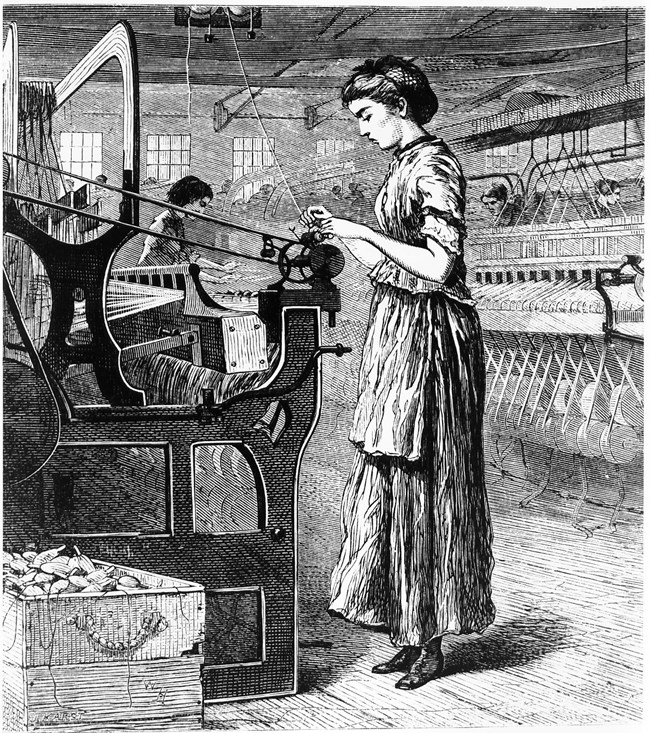

Certainly, by the 1830s, Lowell, Massachusetts, had drastically and permanently changed. The previously agricultural landscape had transformed into a center of textile production, innovative both for its efficiency and for its labor force of young women who mostly came from family farms.

For these workers, familiarly known as “mill girls,” the job came with unprecedented access to books through the many libraries in the town. According to Marshall, The Castle of Otranto was frequently checked out, along with the novel Charlotte Temple, and The Mysteries of Udolpho, and girls often shared the texts with each other and even acted out scenes for entertainment.2

Public Domain.

While far off castles and tyrannical aristocrats might seem a world away from New England factory life, imagine how this passage from Matthew Lewis’s novel The Monk: A Romance might appear to a young woman working in a place like the Boott Mills, an enormous brick building anchored by looming clock towers:

The Castle which stood full in my sight, formed an object equally awful and picturesque. Its ponderous Walls tinged by the moon with solemn brightness, its old and partly-ruined Towers lifting themselves into the clouds and seeming to frown on the plains around them, its lofty battlements overgrown with ivy, and folding Gates expanding in honour of the Visionary Inhabitant [the ghost known as the Bleeding Nun], made me sensible of a sad and reverential horror.3

It’s easy to see how images like this might have come to mind as a mill worker walked to and from the imposing factory buildings – something that would have been in stark contrast to the farms she had left behind. Add to that, the fact that the young women often went to work early in the morning and left after sunset, and mostly saw the factory buildings “tinged by the moon,” a view that could call to mind the settings common in Gothic writing.

Eventually, American writers incorporated Gothic elements directly into descriptions of textile mills and their environments. Take a look, for example, at Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’ description of a storm in a fictional New England mill town in her historical novel The Silent Partner:

The wind was high and blew a kind of froth of noise in gusts against the closed windows and doors; but never laid finger’s weight upon the steady, deadly underflow of sound that filled the night. A dark night….green whirlpools had grown black, and where the tints of malachite and gold and umber, swinging on their bright arms through the dam had become purple and gray and ghastliness, and wrapped the stone piers in dark field, as if they had been mourners at a mighty funeral.4

Of course, the Gothic spoke to more than just the architectural environment. It also created an outlet for thinking through new working conditions. For the first time, work hours were regimented by a clock, rather than cycles of nature as on a farm. In the case of the Lowell women, it was also the first time they left their family home, which put them in a doubly vulnerable position–both as workers, who could be dismissed at any moment or whose wages could be cut without warning or reason, and as women, who were at times victims of unwanted romantic or sexual advances from their male overseers.

The combination of moral and economic uncertainty in this new labor environment gave way to scenes of terror that could most effectively be understood through the exaggerated sensibilities of Gothic tales. The Lowell girls may have also found a sense of power or agency through reading and writing in the Gothic mode, a confidence that would carry over into their own efforts to resist systems of abuse in the mills.

1) Bridget Marshall, Industrial Gothic: Workers, Exploitation and Urbanization in Transatlantic Nineteenth-Century Literature (Cardiff: U of Wales Press, 2021), 5.

2) Bridget Marshall, "‘There is a secret down there, in this nightmare fog’: Urban-Industrial Gothic in Nineteenth-Century American Periodicals,” Women’s Studies 46, no. 8 (2017): 771.

3) Matthew Lewis, The Monk: A Romance, 1796. Reprinted with Introduction and Notes by Nick Groom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016),120.

4) Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, The Silent Partner (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1899), 266-67.

This article is part of the "Literature and Labor series."