Last updated: February 6, 2024

Article

Faneuil Hall, "The Cradle of Liberty"

Library of Congress

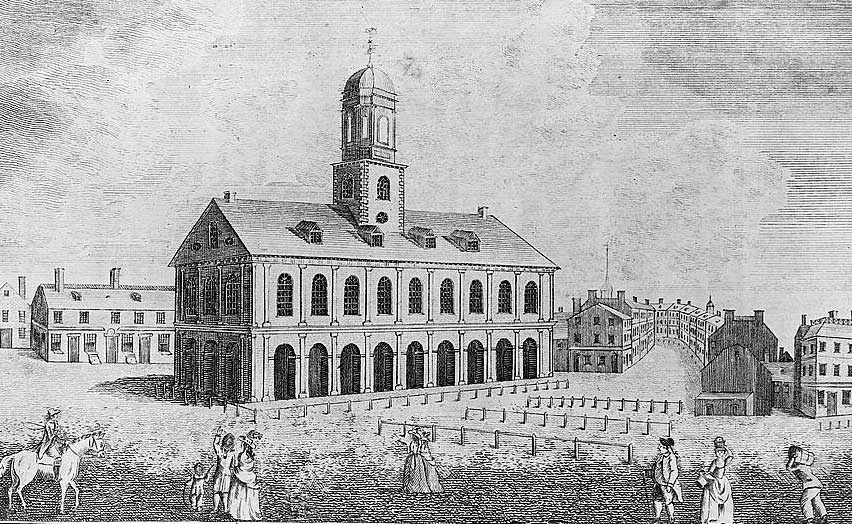

Since 1742, Faneuil Hall has played a crucial role in the ongoing story of our nation. Gifted to the town by the merchant Peter Faneuil, this building served a dual purpose as a marketplace as well as the center of town government. Here, citizens of Boston could gather, discuss, and vote on issues that impacted their lives.

By the 1760s, however, Faneuil Hall took on a more national, if not global, significance. In the early days of what became known as the American Revolution, leaders including Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and others rallied here to protest the policies of the King and Parliament, sparking some of the earliest confrontations that ultimately led to war and independence.

In the decades and centuries that followed, Bostonians continued to gather here to assert their rights and to work for a better future. Abolitionists, suffragists, political leaders, and others have all added their voices to the ongoing conversations about freedom in this sacred hall. Renowned as America’s "Cradle of Liberty," Faneuil Hall continues to be a gathering place for community, conversation, and change.

Peter Faneuil, The Benefactor

Peter Faneuil moved to Boston following the death of his parents, French Huguenots who had immigrated to New York in the early 1700s. Here, he lived with his uncle Andrew Faneuil, a leading merchant and trader in town. When Andrew died, Peter inherited most of his uncle’s estate and business. He quickly became one of the wealthiest merchants in Boston, running a trans-Atlantic trade empire. Like many Boston merchants, Faneuil owned enslaved people of African descent, traded extensively in goods produced by enslaved labor, supplied materials that supported plantation economies, and his capital directly funded several voyages to purchase enslaved Africans off the coast of Sierra Leone.

With his vast resources, Faneuil approached the town's government—the town meeting—with a proposal to fund and establish a permanent central marketplace in the heart of Boston. To help garner support for this, he offered to add a meeting hall (today known as the Great Hall) over the market floor to house Boston’s town government. Construction completed in 1742 and the town voted to name the hall in Faneuil's honor.

The Cradle of Liberty

Faneuil Hall quickly became an invaluable part of Boston's political, cultural, and social life. It served as home to town meeting, as well as a public space for concerts, banquets, and other civic ceremonies.

After a fire gutted the interior in 1761, the building reopened in 1763, which coincided with the beginning of controversial taxation policies imposed upon the colonies by King and Parliament. The hall soon became an epicenter of colonial protest. For example, in this hall Samuel Adams, John Hancock, James Otis, and others lashed out against such laws as the Sugar and Stamp Acts, and called the earliest meetings that ultimately led to the Boston Tea Party. Here they kindled the first flames of the struggle that soon led to war and independence. For its role in these early days of the American Revolution, Faneuil Hall soon became known as the "Cradle of Liberty."[1]

Boston Public Library

As the town grew in the years following American independence, Faneuil Hall did as well. Town officials hired the architect Charles Bulfinch to expand the building to its current footprint, which reopened in 1806. In 1822, Boston moved away from its town meeting form of government when it rechartered itself as a city, run by a mayor and alderman board. Though it no longer used Faneuil Hall as the center of government, the City of Boston retained the building so that it could continue to be a forum for public discussion and debate as well as an active place for gatherings, ceremonies, and other aspects of civic life.

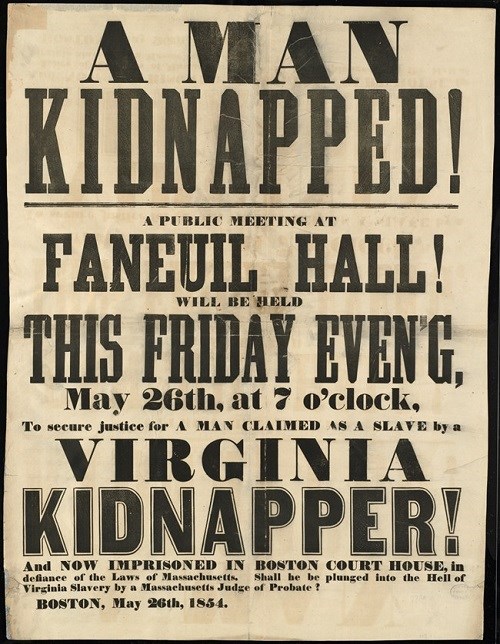

Political leaders, activists, and other changemakers of all kinds continued to meet at Faneuil Hall in the years that followed. For example, abolitionists including William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass and others gathered time and again at the hall to advocate for the end of slavery and assist those seeking their freedom on the Underground Railroad. At the time, anti-abolitionists and even pro-slavery leaders such as Jefferson Davis rallied at the hall. Similarly, activists both for and against women’s suffrage used the hall in the decades leading up the 19th Amendment, which granted the right to vote to women. For instance, suffragist Lucy Stone and others drew upon the Revolutionary legacy of the hall when they held the New England Woman’s Tea Party here in 1873. Throughout the 1900s, Faneuil Hall hosted countless other meetings of labor activists, political leaders, and civil rights organizations, including the Gay and Lesbian Town Meetings of the 1970s and beyond.

In his final campaign speech before the presidential election in 1960, John F. Kennedy addressed the nation from Faneuil Hall. He said:

I think this old hall reminds us of how far we've been as Americans and what we must do in the future...It reminds us of our great history, of what our people have been willing to do in order to build our society...[2]

Photo by Matt Teuten. Courtesy NPS/National Parks of Boston

The Hall Today

In keeping with Kennedy’s words, to this day, Faneuil Hall remains a continuously used public meeting space for political rallies, grassroots activism, and other civic events, including naturalization ceremonies. Faneuil Hall, America’s "Cradle of Liberty," remains a vital part of the ongoing and unfinished story of our nation.

In addition to housing the marketplace and hall, Faneuil Hall today now serves at a gateway visitor center to the National Parks of Boston, which includes an education and film space. The Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company continues to maintain an armory and museum on the top floor, which it has for generations.

Footnotes

[1] For an early example of this moniker, see Boston Price-Current, August 17, 1797, "Faneuil Hall – The cradle of American liberty was decorated in a style most convenient for the guests..."

[2] "Speech of Senator John F. Kennedy, Boston, MA, Faneuil Hall," The American Presidency Project, accessed February 2024, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/speech-senator-john-f-kennedy-boston-ma-faneuil-hall.