Last updated: December 1, 2024

Article

Helen Whittier

Introduction

While Lowell’s Mill Girl era stands as a period of social progression for women, the familial hierarchy that made up the textile corporations still strictly adhered to 19th-century expectations, with a male father-figure in charge of the whole operation. That is, save for one woman: Helen Augusta Whittier, who defied tradition by successfully managing her own mill. Helen is considered the only woman to ever own a major textile manufacturing company in the United States. This significant achievement was only one of many, her life rich with instances of community leadership for the betterment of Lowell as well as activism toward women’s rights and suffrage for the entire nation.

“Occupations for Women. A Book of Practical Suggestions, for the Material Advancement, the Mental and Physical Development, and the Moral and Spiritual Uplift of Women : Willard, Frances E. (Frances Elizabeth), 1839-1898” Internet Archive, January 1, 1897

Early Life and Family

Helen Whittier was born in Lowell in 1846 to parents Moses Whittier and Lucindia Blood. Only one of her siblings survived into adulthood, an older brother named Henry. Helen’s upbringing was atypical compared to many women in the 19th century. She received a formal education, graduating from Lowell High School before attending Lasell Female Seminary (now Lasell University) where she studied art and art history. Helen was supported by her father and his successful career, working as an overseer in the cloth dressing rooms at the Merrimack and Boott Cotton Mills before starting his own business manufacturing loom harnesses, rope, twine, and more. This family enterprise grew into the Whittier Mill standing today on Stackpole Street.

Taking Over the Mill

In 1884, Moses Whittier passed away. A few years earlier, he had relinquished control of his company to his son Henry. Unexpectedly, though, Henry died in 1888 from Bright’s disease, a kidney disorder today recognized as nephritis. With no other heirs to the Whittier Manufacturing Company, Helen stepped up and became President and Treasurer of the enterprise at the age of 42. She brought on her cousin Nelson to superintend the mill and its 70 employees, later transferring the title of Treasurer to him as well while focusing on her leadership role for the next 13 years.

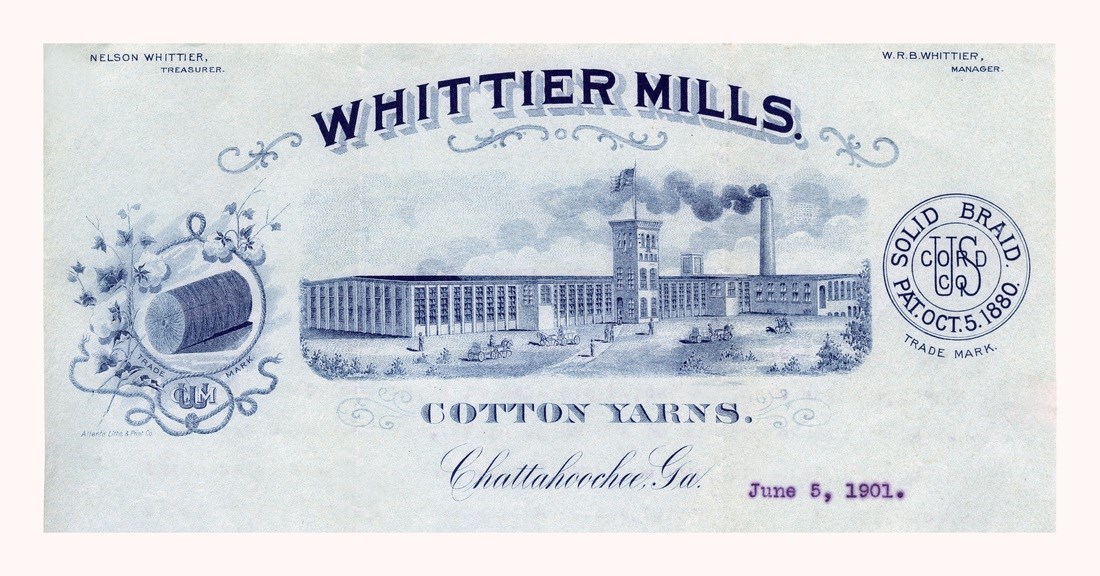

Despite nationwide economic strife brought on by the Panic of 1893, Helen sought to expand the Whittier Manufacturing Company in the years to follow. After attending the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, she made the decision to open a new mill along Georgia’s Chattahoochee River to take advantage of the nearby abundant cotton production. According to an Atlanta newspaper, she even handpicked the site and flipped the first switch to get the new mill running. This business move—taking advantage of proximity to cotton as well as labor that was less regulated and more affordable—would be adopted by most northern textile mills in the decades to follow.

Whittier Mill Village. http://www.whittiermillvillage.com/history.html

Many who owned Lowell-based textile mills typically ran their companies from the upscale comforts of Boston. Helen did something similar, choosing to stay in Lowell while cousin Nelson and his immediate family moved down to Atlanta to manage the expansion. She continued to blaze a trail into the wider professional community of Lowell, joining the Middlesex Mechanics Association, an organization her father Moses was Treasurer of decades prior. In the midst of managing her mill in Lowell while building a new mill down south, she also served on a committee within this organization responsible for establishing the Lowell Textile School, an early center of academia focused on textile manufacturing education.

In 1901, after over a decade of leadership with her family’s mill, Helen stepped down as President after Paul Butler, son of former Massachusetts Governor Benjamin F. Butler, became a primary shareholder. Butler soon closed the original Lowell mill to consolidate production in Georgia. At home in Lowell, Helen returned to teaching art history and playing leading roles in the betterment of her community.

Activism in Lowell and Beyond

While the act of owning a major textile manufacturing company in the 19th century is enough on its own to cement Helen Whittier’s place in history, this period was, in truth, simply a single chapter of a storied life.

After completing her schooling at Lasell Female Seminary, Helen returned to Lowell and taught porcelain painting at the Lowell Evening Drawing School. Her artistic skills would later earn her a table at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, presenting an elegantly designed Brussels carpet. Outside of her profession, she played a pivotal role in establishing multiple organizations to bolster the community.

In 1868, at the age of 23, Helen helped create a literary society for women, first called the Charles Dickens Club (in honor of the author who had recently visited Lowell), later renamed the XV Club for its number of members. At 32, she also served as a founding board member of the Lowell Art Association, one of the oldest incorporated art associations in the country. Additionally, in 1884, Whittier joined one other woman and six men in establishing the Channing Fraternity, a Unitarian group designed to provide aid for impoverished citizens, hold open religious meetings, and organize lectures, concerts, and other forms of entertainment for the community at large.

With an amplified voice and years of leadership experience to her name, Helen also looked to empower the women around her. In 1896, while still running her family’s company, she helped form the Middlesex Women’s Club, serving as its first president. Women’s clubs were instrumental in gathering women for civic education and activism; they made formal schooling accessible when it was otherwise limited and gave them a means to be heard when not yet given the right to vote. The Middlesex Women’s Club would become one of the largest of its kind in the country, boasting over 600 members.

Following the sale of her company, Helen moved to Boston and invested her efforts in women’s rights on a larger scale. In 1903, she joined the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) and, alongside author May Alden Ward, founded its first publication, the Federation Club Bulletin—the two served as its first editors. The following year, Helen became president of the Massachusetts State Federation of Women’s Clubs and served in this role until 1907. Then, in 1916, she became the State Director for the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA), an organization that had been advocating for women’s suffrage since 1870—she stayed in this role until 1919.

Harvard Radcliffe Institute: Schlesinger Library / Collections

Legacy

Helen Augusta Whittier died in Boston in 1925 at the age of 78. She was buried alongside her family in Lowell Cemetery. The impact of her accomplishments and contributions are still felt in numerous ways today. The Lowell Textile School that she helped draft a proposal for later merged with Lowell State College, progressively evolving into its current shape as the Francis College of Engineering at UMass Lowell. The Lowell Art Association she founded in 1878 also exists today within the Whistler House Museum of Art. And shortly after her death, the Massachusetts State Federation of Women’s Clubs established the Helen A. Whittier scholarship at UMass Amherst. This is available to business students majoring in Managerial Economics, harkening back to her impressive time spent as President of the Whittier Manufacturing Company.

Today, the Whittier Mill Village established in Georgia is one of 17 historic districts in the city of Atlanta. And the original Lowell mill building constructed by her brother and father still stands on Stackpole Street, now accommodating the Lowell Housing Authority.