Last updated: April 21, 2025

Article

Historic Gardens at Grand Portage

NPS photo

Historic Vegetables

The Grand Portage historic gardens are located outside the palisade walls by the Anishinaabe Odena (Ojibwe Village), and inside the palisade behind the kitchen. The North West Company operated its post here from 1778 to 1803. Many vegetable varieties grown in the garden now date back to the 1700s and early 1800s. Vegetable varieties from 200 years ago and earlier are still available today because Native American and early settler families saved seeds from their harvests to plant in the following year. The seeds saved were handed down from one generation to another.

NPS Graphic / G.M. Spoto

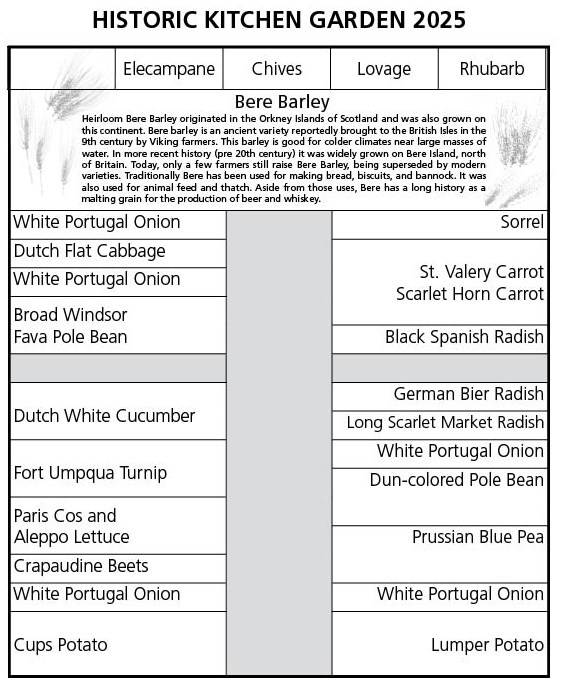

- Elecampane: Herb also known as elfwort or horseheal, used primarily as a medicinal for lung issues, also anti-bacterial. Tincture from the root used as a cough suppressant.

- Chives: A unique variety found growing naturally on the Grand Portage Reservation

- Lovage: also known as “mountain celery” this herb is a common 18th century flavor which has fallen to the side over time.

- Victoria Rhubarb: Sugar because more available and cheaper in the late 18th century, and rhubarb recipes appear by 1800.

- Sorrel: This perennial herb has a famed citrus taste. Used often when lemon is needed. Sorel is common in our salads and soups. It is usually the first green we see in the GRPO garden.

- Broad Windsor Fava Bean: The most common of all the Fava beans in 18th century America. Large in size and high in protein, the mild flavor of the bean does well in dishes.Young pods can be eaten like snap beans. Another cold loving vegetable known in 18th century Canada.

- Dun-Colored Pole Bean: Mentioned in Ambercrombie’s 1778 work Every Man his Own Gardener as both an early snap-bean and dried for soups. A classic sickle-shaped pod and rare, prolific bean. The penultimate 18th century Anglo-American culinary bean.

- Dutch White Cucumber: Since the early 1700s this variety has been grown in America. White cucumbers seem to have lost favor as the 19th century continued.

- White Portugal Onion: Also known as Philadelphia White and Philadelphia Silver Skin, this variety was introduced from Portugal in the 1780s. It normally produces a number of small bulbs that are excellent for pickling or for use as pearl onions.

- Fort Umpqua Turnip: Heirloom variety found growing at the site of Hudson’s Bay Company Fort Umpqua, a 19th century post in the Pacific Northwest.

- Crapaudine Beet: Dating back to the 1600s, a variety whose name comes from the French word for a female toad. Often roasted over the fire until it’s jacket slips revealing it’s bright red flesh considered by many the deepest most savory flavor of any beet roasted., while revealing an almost chestnut like aroma. The long carrot-shaped roots are covered with a black bark-like skin making it very winter hardy.

- Scarlet Horn Carrot: Earliest known orange carrot in North America.. This variety was known to the fur traders and Metis people of the Red River region in NW Minnesota and Winnipeg, Manitoba.

- St. Valery Carrot: also known as the “James Scarlet” is an early graceful intense flavored French variety with a hint of ginger.

- Prussian Blue Pea: The classic 18th century pea. The pea of the 18th century, grown also by Thomas Jefferson. This are seeds collected from the first growing of this variety at Grand Portage in 2022.

- Black Spanish Radish: Visitor favorite, like a large black baseball, this 18th century variety always grows well here. A fantastic treat to slice a slab and fry in butter!

- German Bier Radish: Small red radishes are just about to become a more popular option, but these bigger root vegetable radishes were popular for feeding men at a Fur Trade or Military Post. Eaten raw or treated as a potato and baked or mashed.

- Long Scarlet Market Radish: Long, red-skinned and less pungent, this radish escapes the larger classified “keeper” radishes found elsewhere in our garden. A beautiful crisp radish more akin to a carrot in shape. A more refined “sallad” radish.

- Spotted Aleppo Lettuce: During the time of the Northwest Company this lovely tender lettuce was known to have been available in the Philadelphia seed catalogues. One of the most popular and beautiful varieties in the 1700s.

- Paris White Cos Lettuce: This “romaine” type lettuce dates back to atleast 1794 and is another vegetable known to have grown in Thomas Jeffersons garden.

- Flat Dutch Cabbage: Brought to America by early Dutch travelers. This variety appears in Canada’s first nursery catalogue of 1827. One of oldest cabbages in cultivation.

- Cups Potato: A small light brown to pink tuber with russet skin, Cups is one of the oldest documented British heirloom potatoes. Dating back to the 1770s, Cups survived the Irish Potato Famine. This variety may be better suited for agriculture than the dinner table. Grand Portage is one of a very few historic gardens in the U.S. growing an 18th century potato variety.

- Lumper Potato: The great Irish Lumper, remnant, and culprit of the Potato Famine. Sadly described as “wet, tasteless and unwholesome”. The Lumper was the variety eaten by Ireland’s poor and the variety most affected by late blight at the start of the outbreak. Apple, Cup and Lumper were 3 potatoes eaten in Ireland at this time. Apple and Cup were considered quite edible, but the Lumper was most reviled. It was considered wretched, unpalatable, unfit for humans, and even beasts would reject them if another variety was available,” said one historian. “It seems that the Lumper’s abundance was based solely on economics. It outyielded the others by as much as 30 percent. At a time when hungry bellies were plentiful, people filled them with Lumpers - four million people could be fed on a potato that was considered ‘scarcely food enough for swine.’ How bad could it be, if an entire population was living and thriving almost exclusively on it?”

- Bere Barley: Common at Fur Posts, among the earliest known barley. Heirloom Bere Barley originated in the Orkney Islands of Scotland and was also grown on this continent. Bere barley is an ancient variety reportedly brought to the British Isles in the 9th century by Viking farmers. This barley is good for colder climates near large masses of water. In more recent history (pre 20th century) it was widely grown on Bere Island, north of Britain. Today, only a few farmers still raise Bere Barley, being superseded by modern varieties. Traditionally Bere has been used for making bread, biscuits, and bannock. It was also used for animal feed and thatch. Aside from those uses, Bere has a long history as a malting grain for the production of beer and whiskey.

The Seed Trade

American Indian tribes had well established trade routes long before the first European explorers arrived in North America. Along with other items, seeds were traded among Indian tribes. The explorers and settlers brought their seeds with them to North America. When the Indians and early settlers started trading, seeds were among the objects exchanged. Indians adopted peas and parsnips, and the settlers began growing beans, squash, and corn in their gardens.

The Original Grand Portage Garden

According to diaries of fur traders who were at Grand Portage, the main crop grown in the garden was potatoes. Diaries of fur traders at interior North West Company posts beyond Grand Portage and a 1797 inventory taken at Grand Portage suggest that other vegetables were grown as well. The garden provided fresh vegetables for North West Company gentlemen who came for Rendezvous. The garden also produced vegetables for winter storage and use by the few Company employees who were stationed at Grand Portage for the winter. Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) women and sometimes voyageurs planted and tended the gardens.

NPS photo

Today’s Garden

The present garden consists of two raised beds. The beds are not historic because the ground under the beds has not been completely excavated by archeologists. Raised beds are a way to re-create the original gardens and not disturb any artifacts that are still in the ground underneath the beds. Gardening was a traditional summer activity of the Ojibwe women.

The Three Sisters garden bed, located outside the palisade by the Ojibwe Village, shows a traditional Native American style of planting. The Three Sisters – corn, beans, and squash – are grown together in a field. The Three Sisters balance and nourish each other. Corn is planted in hills and feeds heavily on the soil. Beans send their runners up the corn stalks and add nitrogen to the soil. Squash is planted at the ends of corn fields and also between corn plots in a field. Squash sends its long, prickly runners through the small rows discouraging both small animals and weeds as well as helping to hold moisture in the ground.

The garden bed located inside the palisade behind the kitchen represents a typical fur trade kitchen garden. The kitchen garden is planted with a mix of Native American, European, and Asian vegetables and herbs. A more European-gardening style is used, with vegetables planted in rows instead of hills and beans running up poles rather than cornstalks.

NPS photo

The Importance of an Heirloom Garden

The historic seeds used in today’s garden are called heirlooms. Heirlooms are open-pollinated seeds that were grown before the 1940s. Plants grown from open-pollinated seeds will reliably reproduce seeds with the genetic blueprint for that same plant year after year. As a result, open-pollinated seeds are ideal for saving and using in next year’s garden.

Newer hybrid seeds were first developed and sold in the 1930s. Hybrids combine desirable qualities of their parent plants such as high yield under many conditions and disease resistance. However, hybrid seeds must be produced under controlled conditions and cannot be reliably saved. Seeds saved from hybrid plants tend to revert back to one of the parent plants, or be sterile. Hybrid seeds must be obtained each year from various seed companies. Because of their desirable qualities, farmers started using hybrid seeds and stopped saving Heirloom seeds. As a result, many older vegetable varieties were lost forever.

The loss of older open-pollinated vegetable varieties has resulted in less genetic diversity in the world’s food crops. Genetic diversity is needed to help maintain a stable world food supply and to provide breeding stock to produce hybrids. The danger of disease wiping out a whole vegetable crop is high if there are only a few open-pollinated varieties of that vegetable remaining.

By researching, locating, growing, and saving heirloom seeds, the historic gardens at Grand Portage National Monument are helping to preserve the genetic diversity in the food plant world.

What You Can Do

- Support or join a non-profit seed saving organization

- Consider growing one or two heirloom plant varieties, saving the seeds, and handing them down to the next generation