Last updated: February 7, 2025

Article

History of Lighthouses in the United States

Boston Public Library

Colonial Period (1607–1789)

During the colonial period in America, individual colonies provided aids to navigation. In the 17th century they typically used beacons as aids, often lighted. For example, colonists built fires on Beavertail Point to guide vessels at night in Newport, Rhode Island, soon after it was founded in 1639. However, in addition to serving as navigational aids, chains of lit beacons also helped warn those along Narraganset Bay of approaching enemy ships during the French and Indian and later the Revolutionary War.[1]

Similarly, Boston used beacons, too. Like Narraganset Bay, one on the eponymous Beacon Hill, erected in 1635, helped warn inland areas of invasion. A similar lighted warning beacon was also constructed on Point Allerton in Hull in 1673, and a daybeacon may have been built on Great Brewster in 1679 or 1681.[2]

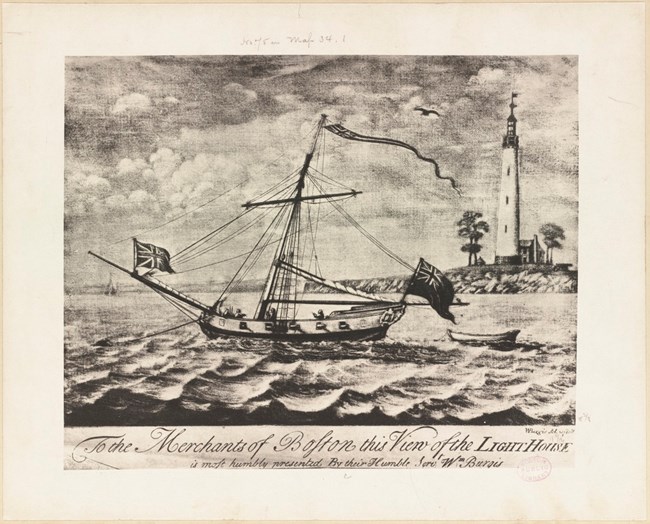

These warning beacons did not, however, guide ships through the islands and shoals of Boston Harbor. To mark the entrance to the harbor and thereby benefit trade, a group of merchants petitioned the legislature for a lighthouse in 1713. Little Brewster was chosen as the site, and in 1716 the construction of Boston Light was completed—the oldest lighthouse site in North America.[3] Other colonies also needed guides to their ports. Subsequently, 11 additional lighthouses were built before 1789, including Sandy Hook, New Jersey, 1764 (still standing as the oldest lighthouse in the United States).[4]

Secretary of the Treasury and Commissioner of Revenue (1789–1820)

In one of its first acts after its formation in 1789, the US government assumed control of all aids to navigation in the country. This included the 12 existing lighthouses at the time, as well as those under construction. The US government placed them under the Treasury Department. From 1789 to 1820, the number of lighthouses increased to 55, though apparently without any formal system.[5]

Fifth Auditor of the Treasury (1820–1852)

In 1820, fifth Auditor of the Treasury Stephen Pleasonton took control of navigational aids. Due to Pleasonton’s fiscal frugality, dedication to other responsibilities, and lack of maritime experience, the lighthouse service suffered greatly through his 32-year tenure. An 1838 survey by naval officers found that the condition of the lighthouses ranged from good to terrible—many were poorly placed, of faulty construction, and had poor quality lights. Nonetheless, Congress took no action. Congress again failed to act in 1845 on recommendations from navy officers.

Boston Pictorial Archive

Finally, in 1851, after years of protest from shippers, navigators, chambers of commerce, and the publishers of the American Coast Pilot, Congress appointed a special investigative board. After thorough study, this board recommended the establishment of a lighthouse board composed of navy officers, army engineers, and civilian scientists. Congress quickly complied and in 1852 created the US Lighthouse Board.[6]

One innovation during the Pleasonton years had been the use of lightships—vessels moored in shallow water or near shoals where a lighthouse could not be built. The first lightship in the United States was installed at Willoughby Spit, Virginia, in 1820 but soon moved to Craney Island near Norfolk, Virginia, and quickly followed by four more in Chesapeake Bay. Like other navigational aids, lightships suffered during the Pleasonton administration—vessels were wooden, not designed for heavy seas, poorly equipped, manned by landsmen, and lacked relief ships.[7]

US Lighthouse Board Innovations and Organization (1852–1910)

In 1852, the newly established US Lighthouse Board took over operations of 331 lighthouses, 42 lightships, and other navigational aids, including numerous buoys. The board made many improvements, among them in the administration of lighthouses. The board divided the country into 12 lighthouse districts, the twelfth being the West Coast, where the board built their first lighthouses. Each district had its own inspector, usually a navy officer, and later also an army engineer. The board issued detailed written instructions to the keepers. With the help of the Civil Service Reform Acts of 1871 and 1883, they gradually changed the keepers from patronage appointments to professional civil servants.[8]

NPS Photo

The US Lighthouse Board also made many technological improvements, including the installation of Fresnel (pronounced Fruh-NEL) lenses. Frenchman August-Jean Fresnel developed the lenses in the 1810s and they were installed in French lighthouses in the early 1820s. The lenses, composed of concentric circles of prisms, directed the light to a central bullseye which concentrated it. This resulted in a far brighter light than that from any other contemporary lens. By the Civil War, all US lighthouses had Fresnel lenses.[9]

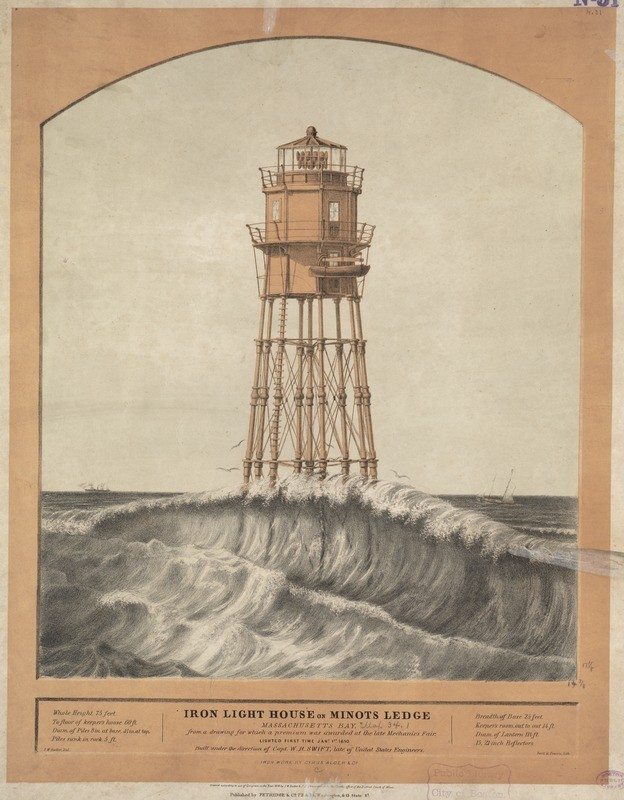

Other technological improvements concerned lighthouse construction, lightships, buoys, and lamps. lighthouses were constructed of interlocking stones in wave-swept locations. Screwpile and sunken caisson foundations were also introduced in this period.[10]

Screwpile lighthouses replaced many lightships in Chesapeake Bay—by 1889 the total number of lightships dropped to 24. But with the development of iron steam-powered ships, the number again increased until there were 56 lightships in 1909.[11]

The lighthouse board replaced earlier copper-clad wooden buoys with iron ones, color-coding all buoys and other markers. Buoys still used bells, then later whistles, first introduced in 1876. Gas-lighted buoys began to be used in 1882.

They also made improvements to fog signals. Mechanically rung fog bells were introduced in the 1850s, later replaced by steam whistles, reed-trumpets, and siren-trumpets. Changes to navigational aids were published in the Notice to Mariners, a supplement to the Light List, which recorded all aids, their locations, and characteristics.[12] At the end of this period, the incandescent oil vapor (IOV) lamp was introduced. Similar to a huge Coleman lamp but fueled by kerosene, the lamp produced a far brighter light than earlier ones without increasing fuel consumption.[13]

By 1910, there were 11,713 navigational aids of all types in the United States—this included 1,397 major lighthouses (compared to 297 in 1852). Too cumbersome for the administrative structure set up in 1852, Congress wanted lighthouses controlled by civilians rather than the military. In 1910, Congress abolished the old lighthouse board and created the Bureau of Lighthouses under the Commerce Department, to which lighthouses had already been transferred in 1903.[14]

Bureau of Lighthouses or US Lighthouse Service (1910–1939)

Under the 25-year administration of George R. Putnam, the number of districts in the Lighthouse Service, as it was generally called, expanded to 17.[15] The Bureau placed the districts under civilian superintendents. During this time, navigational aids increased to about 24,000, most of them buoys and small lights.

Important technological advances were also made in this period. Electrification of lighthouses, which began in 1900 but proceeded slowly because of lack of electrical lines, progressed rapidly in the 1920s and 30s as electricity became more available. Powering lights by electricity rather than oil meant fewer duties for keepers, leading to a reduction in the number of lighthouse employees and ancillary buildings, which eventually would lead to automation.[16]

US Coast Guard (1939–present)

In 1939 the US Lighthouse Service was transferred to the US Coast Guard. Under the Coast Guard, automation proceeded apace, as the Lighthouse Automation and Modernization Program (LAMP) began in the mid-1960s.In the 1960s, lightships were replaced by structures similar to oil drilling platforms. By the 1970s, large navigational buoys (LNBs) replaced lightships as well. The last lightship (Nantucket I) was decommissioned in 1985. By 1990 all lighthouses in the country had been automated except Boston Light. After serving faithfully for 215 years, Boston Light was the last lighthouse in the country to be automated in 1998. Though electrified, Boston Light remained staffed due to an authorization by Congress in 1989. However, following the retirement of Dr. Sally Snowman in 2023, Boston Light is no longer staffed by a lighthouse keeper.[17]

Prepared by Nancy S. Seasholes, 2009

Updated in 2025

Footnotes

[1] Sarah C. Gleason, Kindly Lights: A History of the Lighthouses of Southern New England, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1991), 4–6.

[2] Sally R. Snowman and James G. Thomson, Boston Light: A Historical Perspective, (Flagship Press, 1999), 2–4.

[3] Snowman and Thomson, 4–6.

[4] Snowman and Thomson, 180; Lighthouse Friends, "Morris Island, SC," 2001b, http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=333; Lighthouse Friends, "Sandy Hook, NJ," 2001c, http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=378; Rudyalicelighthouse.net, "Cape Henlopen Light, 2006, http://www.rudyalicelighthouse.net/MdAtLts/CpHn/CpHn.htm; See "Beavertail Light," "Brant Point Light," "Great Point Light," "New London Harbor Light," "Plum Island Light," "Plymouth Light," "Portsmouth Harbor Light," and "Thacher Island Twin Lights," by Jeremy D’Entremont, "New England Lighthouses: A Virtual Guide," NEW ENGLAND LIGHTHOUSES: A VIRTUAL GUIDE - Home.

[5] Dennis L. Noble, Lighthouses & Keepers: The U. S. Lighthouse Service and Its Legacy, (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 6–7.

[6] Noble, 7–12; National Park Service (NPS), "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001, https://www.nps.gov/history/maritime/light/admin.htm

[7] Noble, 129–32.

[8] Noble, 12, 28–29; NPS, "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001.

[9] Noble 22–25; NPS, "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001.

[10] Dudley Witney, The Lighthouse, (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975), 37–40, 44–45.

[11] Noble, 130; Willard Flint, "A History of U. S. Lightships," 3, http://www.uscg.mil/History/articles/Lightships.pdf.

[12] NPS, "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001.

[13] Noble, 34.

[14] Noble, 30–32; NPS, "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001.

[15] Snowman and Thomson, 43.

[16] NPS, "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001.

[17] Noble, 38–40, 146–47; NPS, "Lighthouses: An Administrative History," 2001.