Last updated: August 18, 2020

Article

Household Management at Hyde Park

NPS Photo

Managing a house for luxurious living required a large staff of servants. As was customary in homes of the wealthy, three department managers—the housekeeper, butler, and chef—supervised the Vanderbilt household staff. The housekeeper supervised four chambermaids, a parlor maid, and three or four laundresses. The butler supervised two footmen and the houseman. The chef supervised two cooks and a kitchen maid. Additionally, the Vanderbilts employed a valet and a lady’s-maid, and hired other staff when needed for large entertainments.

The servants traveled with the family from house to house—the Vanderbilts maintained five houses and a yacht. Staff usually arrived a day before the family to make the house ready. While respecting social and economic status, Vanderbilt employees did not identify as servants. They were deferential to their employers, but referred to themselves as “the help.” Staff described their employers as “very democratic,” suggesting relationships of mutual respect.

NPS Photo

The Help

The Housekeeper

The housekeeper had authority over key household materials and expenditures. She hired and supervised the female staff, paid their wages, kept the household linens under lock and key, managed supplies, and ordered food for the mansion at the chef’s request. A housekeeper earned from $50 to $150 per month.

The Chambermaids

The chambermaids (or housemaids) were each assigned a floor of the mansion. While the parlor maid was responsible for the first floor, the chambermaids attended to the basement, second, and third floor rooms. The maids cleaned the halls and stairways early. After the occupants left their bedrooms, the maids opened windows for fresh air, stripped the beds of their bedding, and flipped the mattresses. While the bedrooms were airing, the maids cleaned the bathrooms. The duties of Theresa Farley, third chambermaid at Hyde Park, included cleaning The Laundresses the basement, housekeeper’s rooms, upstairs maids’ lavatory, and the grand staircase. Chambermaids earned $18 to $25 per month. They had a couple hours off duty each day, one afternoon and evening each week, and half of every second Sunday.

The Laundresses

The head laundress was a skilled professional, responsible for the care of expensive and delicate house linens. She managed the laundry staff and was responsible for everything that entered and left the laundry, returning it to the housekeeper looking as if it had just arrived new from Paris. The laundry assistants were responsible for servants’ laundry. While in training under the head laundress, they cleaned the laundry room, built the fires, and kept the boilers polished. They worked long hours, often into the evening. A head laundress typically earned $30 per month. The assistant laundresses earned about $18 per month. They had every Sunday off.

NPS Photo

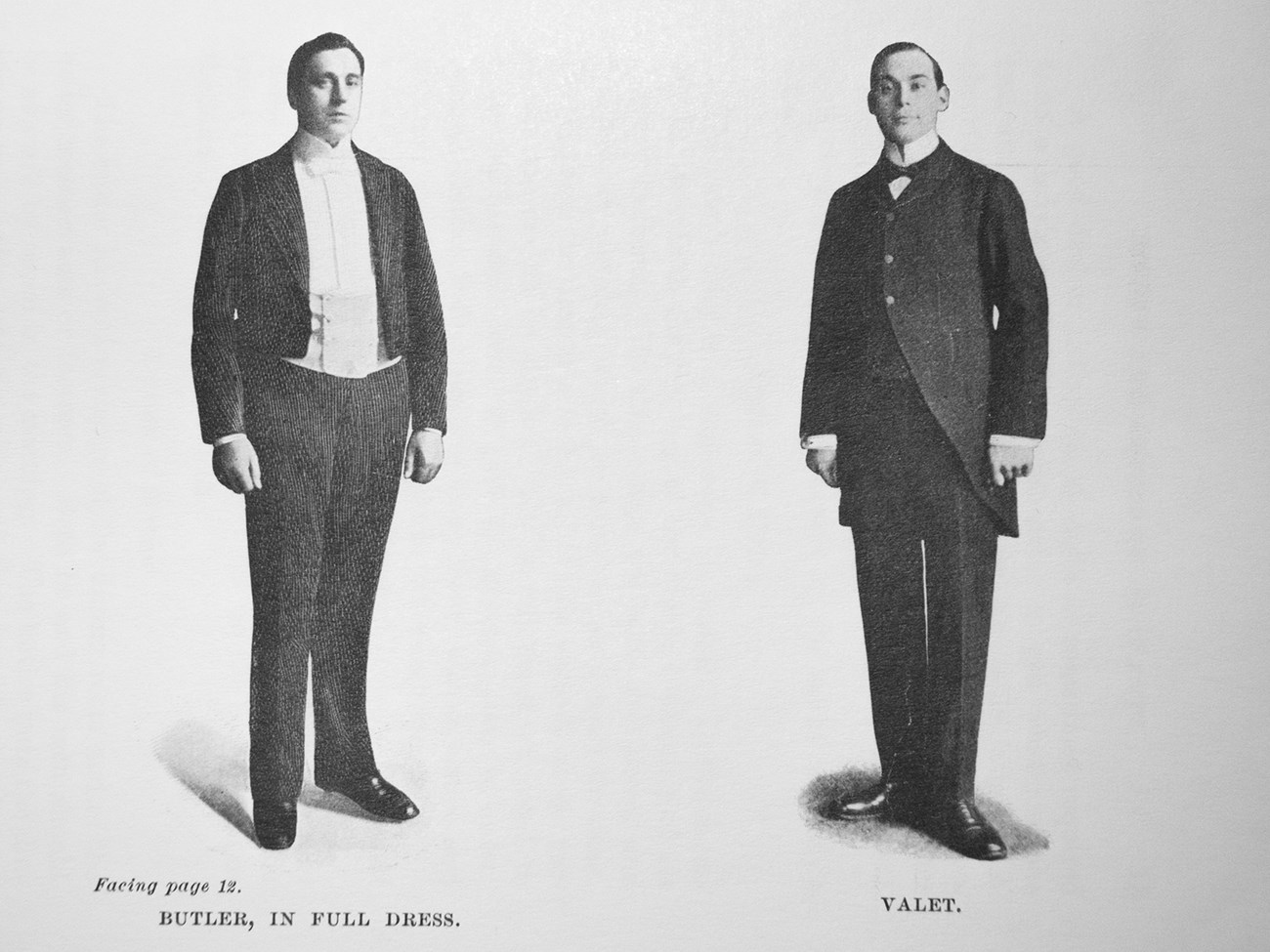

The Butler

The butler and his staff were responsible for the household silver, serving at afternoon and evening meals, answering the door, and caring for the Dining Room and Pantry. In the millionaire’s house, the butler did little besides manage, oversee, and direct the work of the footmen and houseman. He was responsible for the care of wines, including the temperature required for drinking. The butler possessed executive ability, self-command, and dignity.

Second & Third Man (Footmen)

Supervised by the butler, the footmen were on full-day and half-day duty on alternating days. Both men prepared the Dining Room for meals, including polishing the floor and tables, receiving the day’s table linens from the housekeeper, and kept the silver polished. They served at lunch and dinner, attended to bells and the telephone, pulled shades, and prepared trays for tea service. Their wages ranged from $30 to $40 per month.

The Houseman

Called upon by everyone, the houseman, also referred to as the day man or night man, needed an wide assortment of skills. The houseman began his day by tending the furnaces. He then swept the porticos and set out the furniture, delivered wood to the fireplaces, washed windows, ran errands to town, and assisted others as needed. The houseman’s wages ranged from $30 to $40 per month. Thomas Morgan, the Vanderbilt’s houseman, earned $45 per month.

Parlor Maid

The parlor maid cleaned the first floor rooms and worked with the butler and housemen. She was responsible for cleaning the windowsills and floors and dusting the fine objects. She made sure all curtains hung evenly and pulled the window shades to a uniform height. After meals, she assisted in the pantry washing the fine china, silver and glass. A housemaid’s wages ranged from $18 to $25 per month. She had a couple of hours off duty each day, one afternoon and evening each week, and half of every second Sunday.

NPS Photo

The Chef

The chef prepared the Vanderbilts’ breakfast trays placing the proposed menus for the day on Mrs. Vanderbilt’s tray for her approval. Trained in the French culinary tradition, the family’s chefs were described as simple, self-respecting, and hard-working individuals. A chef earned from $100 to $180 per month, and possibly commissions on his market purchases.

The Cook

Cooks and a kitchen maid assisted the chef. They plucked fowl, chopped vegetables, and assisted the chef with all cooking for the family and guests. In addition, the cooks prepared all daily meals for the servants. The kitchen maid (or scullery maid) washed dishes, cleaned the icebox, polished the copper pots and pans, and set the servants’ table.

The Servant’s Livery

Servants wore a uniform known as livery. Most had a morning and afternoon or evening uniform, typically supplied by the family. Thomas Morgan, employed as the Vanderbilts’ houseman from 1900-1909, described staff livery. Early in the day, the butler and his men wore a business-like suit of gray trousers and a dark coat with a black tie. For meals, the butler changed into a suit with tails. The maids wore afternoon livery of dark dress with white apron and a cap. The Vanderbilts expected all staff to be clean, neat, and well dressed.

NPS Photo

-

Hear Alfred Martin, former Vanderbilt Butler

Alfred Martin describes his early training and how he came into the employment of the Vanderbilts as Third Man.

- Credit / Author:

- National Park Service