Last updated: April 2, 2025

Article

A City Response to Yellow Fever

In the late summer of 1793, an outbreak of the mosquito-borne disease yellow fever decimated Philadelphia's growing population. Citizens from all walks of life suffered and died as the city grappled with nearly a dozen burials a day. Anyone who could afford to leave the city, including George Washington and other government officials, quickly fled. Faced with a public health crisis, Philadelphia Mayor Matthew Clarkson published a public message calling on "benevolent citizens" willing to volunteer to help save the city:

"This, it is hoped, may be found among the benevolent citizens, who actuated by a willingness to contribute their aid in the present distress, will offer themselves as volunteers to support the active overseers in the discharge of what they have undertaken. For which purpose, those who are thus humanely disposed, are requested to apply to the Mayor, who will point out to them how they may be useful."

–Mayor Clarkson, September 10, 1793

Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007625050/

The City

Philadelphia was the largest city in the nation with a population of 44,000 residents from the 1790 census. Its size and density made it particularly vulnerable to outbreaks of disease.

Philadelphia in 1793:

- Population of about 50,000

- Population density was an average of 6 people per house

The Volunteer Committee

Mayor Clarkson quickly formed a committee to manage the city’s response to the crisis. Volunteers convened at City Hall (now Old City Hall) and used the building as their base of operations. They met daily from September 14 to November 27, missing only 3 days—all during November as conditions began to improve. The committee focused their attention on those who suffered the most. Their duties included:

- Arranging care for yellow fever patients

- Burying the dead

- Caring for orphans left behind by yellow fever victims

- Management of incoming donations as they allocated resources to those affected by the crisis

John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

https://jcb.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/JCB~1~1~2149~3460006:Bush-Hill--The-Seat-of-Wm--Hamilton?qvq=q:Bush%20Hill;lc:JCBBOOKS~1~1,JCB~3~3,JCBMAPS~1~1,JCBMAPS~2~2,JCBMAPS~3~3,JCB~1~1&mi

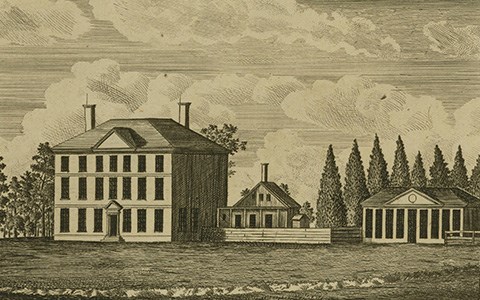

Bush Hill Hospital

“That the Hospital is without order or arrangement, far from being clean, and stands in immediate need of several qualified persons to begin and establish the necessary arrangements... That it is unnecessary to enumerate all the wants: they are numerous...”

–Minutes of the Committee, September 14, 1793

The committee hastily assumed management of the makeshift hospital at Bush Hill, the former estate of prominent Philadelphian Andrew Hamilton. This grand Philadelphia home (a bit over a mile from City Hall) was far removed from the raging epidemic ravishing the city. Although it provided enough space to hold patients, Bush Hill suffered from poor management, chronic understaffing, and supply shortages. Significant upgrades were needed to improve both the function and image of the hospital. Rumors of the conditions spread and some patients fled mid-transit to the hospital.

Volunteers Stephen Girard and Peter Helm took on management of the Bush Hill Hospital. They accepted this important role knowing they might not survive. Through their efforts, the hospital opened its doors to those afflicted to get care and recover. While at the hospital, Girard and Helm remained in constant communication with the rest of the committee at City Hall. The committee hired full-time doctors, apothecaries, nurses, and laborers; and purchased the supplies for the hospital.

When Bush Hill became overcrowded, the committee supplied extra beds taken from the Walnut Street Jail and commissioned the construction of new beds. The committee established rules for attendance and care of patients, and when faced with a staffing shortage, the mayor ordered the release of prisoners to serve as nurses and laborers at the hospital.

“at 11 o’clock in the morning [a doctor] gives them broth with rice, bread, boiled beef, veal, mutton and chicken, with cream of rice to those whose stomachs will not bear stronger nourishment; at their second meal which is at about six o’clock in the evening, he gives them broth, rice, with boiled prunes and cream of rice; the sick drink at their meals porter or claret and water, their constant drink between their meals, is centaury tea and boiled lemonade.”

--Sample Menu from Committee Minutes, October 10, 1793

While the improvement of the hospital was a success, many still died, some after just a few days. A separate building near the hospital was used for the storage of empty coffins and the bodies of the dead until they could be buried.

Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/02013737/

The Role of Black Philadelphians

“the African Society, touched with the distresses which arise from the present dangerous disorder, have voluntarily undertaken to furnishes NURSES to attend the afflicted; and that applying to ABSALOM JONES and WILLIAM GRAY, both Members of that Society, they may be supplied. MATTHEW CLARKSON, Mayor.”

--Dulap's American Daily Advertiser, September 7, 1793

During the darkest days of the fever, the Free African Society provided care throughout the city. False rumors swirled that people of African descent were not affected by a previous yellow fever outbreak in South Carolina and were therefore the obvious choice to provide nursing to the sick. The Free African Society offered care on their own initiative.

Absalom Jones and Richard Allen met with the Mayor Clarkson to coordinate the Free African Society's and the committee's efforts. The city relied on Black Philadelphians for not only nursing, but also for the burial of the dead, another needed service that the Free African Society fulfilled. Although the Free African Society established themselves to help Black people, the society answered the call to help all those in need—regardless of race.

As the fever intensified and members of the Free African Society put themselves in harms way to help others, it became clear that Black Philadelphians did not have special immunity to yellow fever. According to Jones and Allen the number of burials of Black Philadelphians increased fourfold from 1792 to 1793, from 67 to 305.

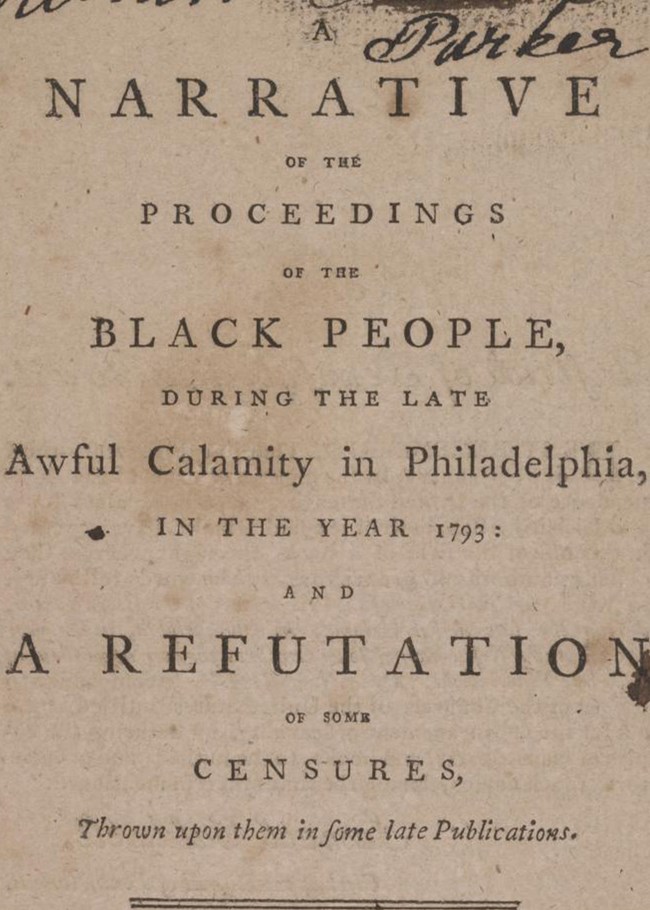

Despite the heroic efforts of Absolom Jones, Richard Allen, and members of the Free African Society, rumors persisted and publications accused Black Philadelphians of stealing from those who they were caring for. Absolom Jones and Richard Allen published a rebuttal to these accusations in "A narrative of the proceedings of the black people, during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: and a refutation of some censures, thrown upon them in some late publications," defending their actions and clearing the good name of the Free African Society.

The Dead

"to his surprise found the father dead, who had been lying on the floor for some days, two children near him also dead, the mother in labour; he tarried with her, she was delivered while he was there, and in a short time both she and her infant expired! he came to the City-Hall, took coffins and buried them all."

–Minutes of the Committee, October 19, 1793

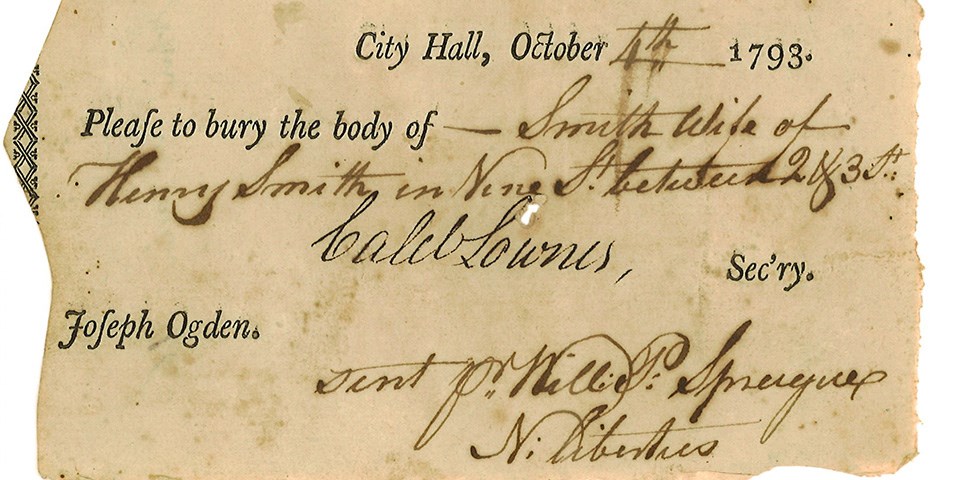

Bodies were left in the streets and in houses - wherever the person had died. Fear of catching the fever prevented many citizens from having anything to do with the sick and especially the dead. Sometimes a person’s body would go several days before someone finally came to bury them. The Free African Society and the committee hired horses, carts, and men to remove bodies to a burial ground.

The high demand of coffins forced the Free African Society and the committee to purchase them for families who could not afford them and those who had no one left in their family to do so. Complaints of improperly sealed coffins would lead to a public notice to coffin makers. The potter's field (now Washington Square) became overcrowded and the city ordered for other suitable burial grounds.

The potter's field caretaker, Joseph Ogden, reported that between the city and a burial ground near Bush Hill, he had buried 1008 bodies. Ogden buried almost a quarter of the 4044 who died through early November. The committee admitted new patients to Bush Hill and ordered burials through mid-November and created blank cards for the burial orders. Over 5000 Philadelphians died from the Yellow Fever epidemic.

Orphans

With so many dying, there was a growing number of children who were left to fend for themselves. Whether their parents or guardians were carried away to the potter’s field or to Bush Hill, these children needed care. The committee obtained a large building to house the orphaned and a matron, Mary Parvin, to care for them.As the fever worsened and the number of orphans grew, the house proved too small to accommodate all those in need. The committee obtained the old Loganian Library, located on 6th Street between Chestnut and Walnut Streets. The Orphan House was one block away from Old City Hall and half a block from the potter’s field.

Nursing orphans were provided food, medical care, clothing, and private nurses. Some orphans stayed there temporarily while their parents were sick while others were given to family members or friends—only after properly proving their relation. The committee's public report regarding care of the orphans:

- 192 orphans total

- 94 given to family or friends

- 27 died

- 71 remained

Thanks to the Free African Society and the Volunteer Committee

The Free African Society and the Volunteer Committee’s work was extraordinary, and ultimately fatal for some of its members. To thank the committee's work, a public committee of citizens, which included Pennsylvania Chief Justice Thomas McKean, met at Old City Hall and adopted a message of thanks. Each person who served on the committee, and the survivors of those that died, would be given a message of thanks along with a piece of silver plate valued at 100 dollars.Members of the Free African Society received no such formal recognition, nor any silver.