Last updated: October 29, 2020

Article

James A. Garfield and the Centennial Exposition of 1876, Part I

Wikipedia

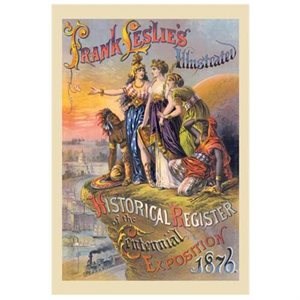

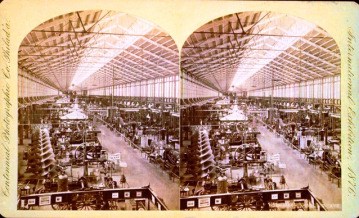

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition called the Philadelphia event the “most stupendous and successful competitive exposition that the world ever saw.” Not that the American Centennial was anything new. Other Expositions grabbed the attentions and the imaginations of people all over the globe, including those held at Paris, Dublin, and Vienna.

Wikipedia

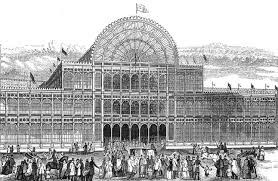

The mania for these exhibitions, also known as expositions, or “expos,” began in 1851, with the Crystal Palace Exposition in London. Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, labored to make the Crystal Palace Exposition reflect “the advancement of industry,” and an event that would highlight “the interests of the laboring people,” while also demonstrating the material affluence and social well-being of English society. Other expositions held in Paris in 1867, in Vienna in 1873, and in several states of the United States were all similarly forward-looking affairs.

In the same way, the American Centennial project was meant to showcase material progress in the United States, but perhaps as important was its original purpose to help heal a society recently torn apart by civil war. Through the celebration of one hundred years of nationhood, the United States would reexamine its moral, social, and political principles.

Wikipedia

The idea of a Centennial celebration, appealed to many people, but it was not universally embraced. James Garfield was an early skeptic. In a diary entry of December 13, 1872, he wrote,

“Congress has been drawn into this scheme unconsciously and is almost now committed to make large appropriations for that celebration. Perhaps we ought to do it, but it ought to have been done in a more open and avowed manner.”

Wikipedia

Jim Davis Collection

As Chair of the House Appropriations Committee, Garfield may have been irked by the international aspect of the centennial as an unaffordable expense. Like so many major undertakings by government in more recent history, the Centennial also became for a time the hostage of partisan and sectional political matters, as is seen in James Garfield’s diary.

On January 10, 1876, he noted that a bill was pending before Congress to grant a general amnesty to former Confederates, allowing them to hold public office. This was controversial. For the first time since the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, “rebel” leaders could occupy seats in the House and Senate.

Jim Davis Collection

Pennsylvania Congressman William D. Kelley made a speech that offered a quid pro quo – passage of the amnesty in exchange for an appropriation for the Centennial. Garfield thought that such a deal “greatly decreased” the chances for an appropriation for the Centennial. An attack by a southern Congressman on the Centennial, “on the ground of its being unconstitutional,” bothered him too. The Centennial might not be affordable, but it was constitutional!

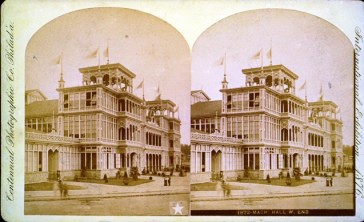

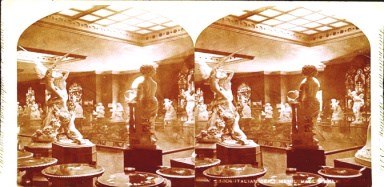

Despite the political maneuverings to which the Centennial was prey, it did proceed, with a mere $500,000 appropriation by Congress. (The bulk of the funding was raised by other means.) Dozens of nations were invited to participate, and dozens did. These included England, France, Austria, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Japan, China, Russia, Brazil, Egypt, and Australia. Hundreds of laborers worked on the construction of its buildings and grounds, and these included many Japanese, Turkish, and Russian workers. The American Centennial was indeed an international affair.

Jim Davis collection

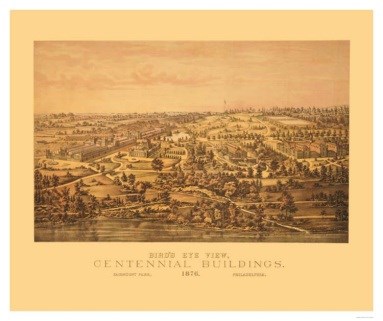

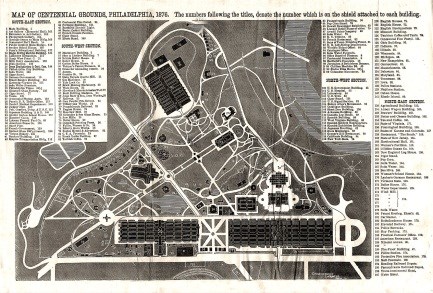

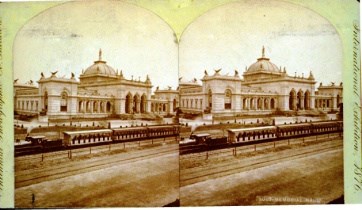

Upon its completion, the physical plant of the Exposition covered 230 acres of ground at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. It was said that the “average visitor…could not help but be awed by the sheer size of everything.” President Grant opened the Centennial on May 10, 1876. Congressman Garfield was at the opening, though he missed the President’s remarks:

Jim Davis collection

Jim Davis collection

Jim Davis Collection

(Check back soon for Part II!)

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2014 for the Garfield Observer.