Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

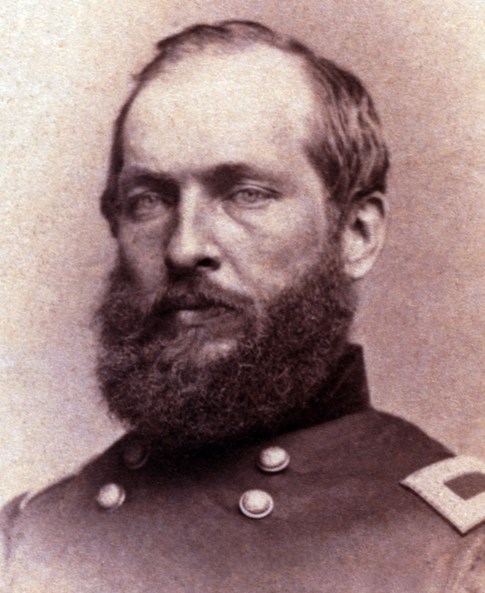

James A. Garfield and the “Yankee Dutchman”: Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel

Library of Congress

Major General Franz Sigel can be reasonably labeled as one of the most controversial commanders of the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. He was at odds with his colleagues within the army due to his foreign background and lack of formal military training from the renowned United States Military Academy. The stubborn, and sometimes arrogant, German general was critical to the Lincoln Administration for the unfading support he gained from German-Americans during the American Civil War. He rallied thousands to fight for the Union cause who took up the pledge “I goes to fight mit Sigel.”

Franz Sigel was born in 1824, in Baden, Germany. He graduated from the Karlsruhe Military Academy in 1843 at the age of nineteen. He served the Grand Duke of Baden until 1848, when he switched sides and joined the German revolutionary movement. He acted as the minister of war for the revolutionary forces and led an army for a short time until the revolution was extinguished by the Prussians. Like thousands of other revolutionaries, he fled to Switzerland, then to England, and finally to New York in 1852. By this time, he had a great deal of prestige among German-Americans from his high-profile role in the rebellion.

Dickinson College

General James A. Garfield put great faith in Sigel’s fighting ability. His letters containing his appraisal of Sigel can be found in The Wild Life of the Army: Civil War Letters of James A. Garfield. Decisiveness of action was lacking in many Union generals early in the war. On May 12, 1862, Garfield wrote of the arrival of Sigel before the battle of Pea Ridge, “It is rumored that General Sigel has arrived with General [Samuel R.] Curtis. I hope this is so. I have great faith in that General and his fighting.” On September 12, 1862, with a growing animosity toward Major General George B. McClellan, Garfield penned, “If under McClellan, may the gods deliver me. If under Sigel, I rejoice.”

Garfield had his chance to first meet Sigel and the entourage of generals under his command on October 5, 1862. While accompanying Kate Chase, daughter of the Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase, Garfield was invited to Sigel’s headquarters for tea. He was stationed nearby with the Army of the Ohio, and was considering a transfer out of that army. Garfield described Sigel as “a very small man, but lithe and well-made.”

Library of Congress

Garfield was intrigued by his German hosts, the majority of them exiles of their own German revolution in 1848 which “threw a crowd of noble fellows upon our shores.” Garfield described the physical characteristics of the generals:

“Nearly all these [the generals] have the same type of form and physique. They are of a small, well-knit frame, their heads and faces are inverted triangles of which the chin is the apex. This gives them great breadth of brain. The four I mentioned were Sigel, [General Carl] Schurz, [General Adolph] Steinwehr, and [General Julius] Stahel.”

After supper, the future president was entertained by the lovely piano play of Schurz and Sigel. He was mesmerized by these cultured men and wrote, “They are both very fine performers, among the very best I ever heard.” He left the party impressed, drawing comparisons between their values and his own countrymen. He wrote, “It is wholly impossible for me to describe the tremendous enthusiasm of these noble fellows. Full of genius, full of fire of their own revolution, and inspired anew by the spirit of American Liberty, and just now by the proclamation which gives Liberty a real meaning. They are really miracles of power.”

Garfield was irritated by the unfair treatment he felt was brought down upon Sigel. The politics, bickering, and favoritism involved within the Army of the Potomac between generals disgusted Garfield, with General McClellan at the helm. He wrote:

“There is that glorious Sigel stripped down to 7,000 men and placed under an inferior both in rank and ability. His men have been sent away to swell McClellan’s already overgrown army, and McClellan refuses to cross the river and has sent here for entrenching tools, while Sigel could, if he had the force, strike a fatal blow upon the rebels’ rear and flank. When he (Sigel) spoke to Halleck about it a few days ago he was personally insulted by him, and Halleck has also charged him with cowardice!! As well charge Marshal [Michel] Ney with cowardice. If this Republic goes down in blood and ruin, let its obituary be written thus: ‘Died of West Point.’

civilwar.org

In November 1862, Garfield served on the court-martial of Major General Fitz John Porter and on Major General Irwin McDowell’s court of inquiry. Garfield gained the admiration and respect of McDowell. McDowell and Sigel had a strong dislike for each other gained during the battle of Second Manassas fought in August of 1862. Garfield began to reassess his appraisal of General Sigel’s military ability following his newfound friendship with McDowell.

The majority of reputations of high ranking officers in Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia were ruined following his defeat at Second Manassas. Garfield recorded that “Every prominent general in Pope’s army either had his reputation ruined or badly damaged in that campaign except [Nathaniel P.] Banks.” Pope had dished out blame to almost all of his corps commanders, including Sigel. Pope’s assertion was seconded by other officers in his army. Garfield wrote: “In his dispatches previous to the battle at Bull Run, he says, ‘Sigel must be crazy.’ And the leading officers with Pope agreed in the opinion that Sigel is a humbug.”

Garfield’s last impression of the man he had so much praise for early in the war was tangled at best. “I am more perplexed to reach a satisfactory judgment concerning General Sigel than any other man I know. I halt between two veins – one leading me to earnest admiration of high qualities, the other to a sad contempt of his charlatanry and unfounded pretensions. On the whole I suspend judgment in regard to him, though I think he has been overestimated and I shall not be greatly surprised, though much grieved, to find that his fame will grow less hereafter,” Garfield recorded.

On May 15, 1864, Sigel was defeated at the battle of battle of New Market, Virginia. There young Confederate cadets from the Virginia Military Institute played a prominent role in his defeat. He was never again given an active command following this embarrassing defeat. Sigel served as editor and was involved in politics following the war, dying in New York City at the age of 77 in 1902.

Written by Frank Jastrzembski, Volunteer, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, September 2016 for the Garfield Observer.