Last updated: November 26, 2024

Article

President John F. Kennedy and the Moonshot: Inspiration and Achievement

Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

“We choose to go to the moon”

These iconic words from President John F. Kennedy are ingrained in American cultural memory, a testament to the ingenuity and wherewithal of the United States and its people. The race to the moon would define not only President Kennedy’s legacy, but it would also be a defining moment in world history. Though Kennedy would not live to see his vision of a manned lunar landing fulfilled, his administration started and enabled a great achievement for the United States in the Space Race. It would also, as first man on the moon Neil Armstrong said, be “...one giant leap for Mankind.”

President Kennedy's role was to propel the ambitious moonshot with the backing of both the American government and the American people.

NASA

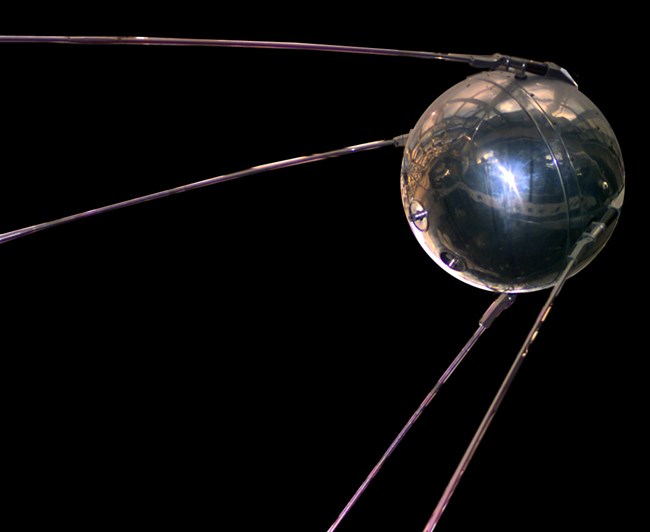

Sputnik: The Race Begins

For over a decade before John F. Kennedy’s inauguration as US president, the United States and the Soviet Union had been engaged in the Cold War. In this ongoing conflict, the two nations sought to triumph over the other in influence, ideology, technology, weaponry and more without engaging in direct war. This conflict grew increasingly dangerous with the rapid building of many nuclear weapons, each one having the capability to kill thousands, threatening not just the United States and the Soviet Union, but the survival of humanity. Many lived in fear of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), where if even one nuclear weapon was used by either side, it would be met with a retaliation of thousands that could readily destroy civilization and life on Earth as we know it. This was a time when new technologies gave one side advantages that deeply worried the other, heightening the chances and worsening the outcome of a war between the two.

In 1957, the Soviet Union unveiled a new and advanced technological achievement: they launched a small satellite, the first of its kind. Named Sputnik I, this satellite was designed to send a simple radio signal as it orbited around the Earth. The success of this mission to send an object to space was not only a first for humanity, but it also demonstrated the Soviet Union’s aerospace technological prowess, causing a great stir among the United States and its allies. They recognized that Soviet rocket technology must be more advanced than previously thought. Therefore, the Soviet Union must have better rocket-reliant nuclear missiles than expected. Between potentially better nuclear arms and having exclusive technological access to space, the Soviet Union had gained an edge in the Cold War. Work immediately began to match the Soviet Union in space in addition to arms.

Though then Senator Kennedy had expressed great concern on a missile gap between the United States and the Soviet Union, he also noted the non-nuclear threats the Soviet Union posed. Addressing the Senate in 1958, Kennedy cited “Sputnik diplomacy,” referring to the Soviet Union’s growing global influence through advances in science and technology, as one of many non-nuclear Soviet threats to the free world. Kennedy’s interest in space grew both as a means of combating growing Soviet influence, and as a way of rallying the people of the United States in a tense, dangerous time in history. Once he was president, Kennedy spearheaded the effort to not only increase America’s competence in space, but to outdo the Soviet space program and thus, instill confidence in the American people.

Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Kennedy Takes Charge

By the start of Kennedy’s presidency in January 1961, further gains had been made by the Soviet Union. They launched a probe that escaped Earth’s gravity, sent probes to the moon, and had successfully returned animals from orbit back to Earth safely. All these accomplishments were firsts in world history, and many, Kennedy included, feared the United States was falling behind.

These fears were reinforced when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin piloted the first manned spacecraft orbit of the Earth in April 1961, just four months into Kennedy’s presidency. In May of that year, Kennedy implored congress to invest further into the space program. Stepping up to the imposing challenge, Kennedy expanded the scope of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and set the goal of a manned mission to the moon, dubbed the “Moonshot,” by the end of the 1960s.

“Now it is time to take longer strides--time for a great new American enterprise--time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on earth.”

~ President John F. Kennedy's Address to a Joint Session of Congress, May 25, 1961

President Kennedy was far from the first person to conceive of a mission to the moon or use the term “moon shot.” The phrase “moon shot” was first used in horse racing, similar in use to how the term “long shot” is used. The earliest known referral to a then hypothetical mission to the moon as a “moon shot” was first used in Rotary Club publication Rotarian in April of 1949. The phrase, referred to as both a “moon shot” and “moonshot”, now not only references space travel to the moon, but can also be used to describe an ambitious project or venture that will have highly significant results.

To better understand and aid the efforts of NASA researchers, Kennedy collaborated extensively with them. He learned quickly of the importance of space exploration, and, though his focus was on the Moonshot and besting the Soviet Union, he embraced other American achievements in space during his administration. On February 20, 1962, NASA astronaut John Glenn Jr. became the first American to orbit the Earth. Kennedy recognized the importance of these accomplishments in both progressing the United States’ space technology and giving hope to the American people.

An Abandoned Idea for Collaboration

Interestingly, Kennedy’s Moonshot idea did not exclusively involve the United States, at least not initially. Originally, in 1961, he had proposed the idea of a joint moon mission to Premier Nikita Khruschev, leader of the Soviet Union. The exact motivations for this proposed collaboration are not clear. Kennedy may have recognized the disparity between United States and Soviet Union space technology and thought a joint mission was the most viable way to get an American on the moon. He may also have thought that a joint mission would lower the rising tensions between the two nations. Ultimately, when Kennedy and Khrushchev met in June 1961, Khruschev turned down the idea. Following Kennedy’s death, the joint-mission concept was never reconsidered by subsequent United States presidential administrations. The first manned mission to the moon, Apollo 11, would be an American one, but not without support from its citizenry.

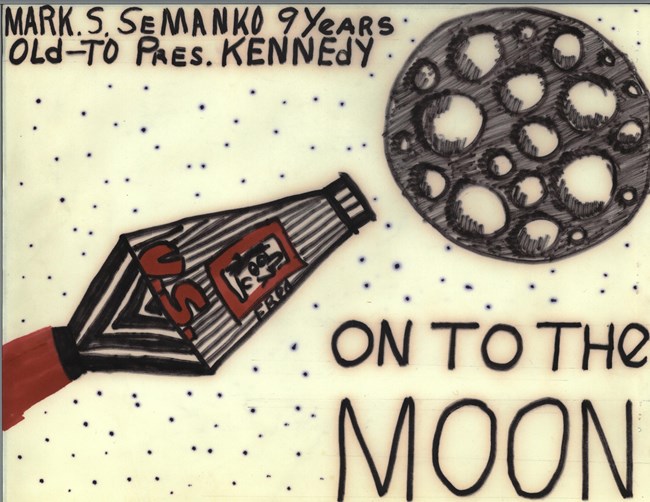

JFKWHCSF-0654-011. Letter and drawing from Mark Semanko to President Kennedy, Fall 1962. Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. White House Central Subject Files.

Winning Support

Getting to the moon was not just a matter of technology, but a matter of support and investment. Many Americans were on board with the United States’ space efforts, but concerns remained.

In addition to the fear of failing to match the Soviet Union’s technology, there were concerns regarding the cost and practicality of a manned moon mission. Some worried the moonshot would be impossible, or so resource-intensive that it was simply out of reach. Kennedy took it upon himself to address these concerns. He stood firm in supporting the importance of the Moonshot as both a victory for the United States, and as a milestone for mankind.

Knowing that inspiring the public was key, Kennedy spoke often of the ambitious and important planned moon mission. The most famous of his speeches on the Space Race was at Rice University. He was well aware many were daunted or doubtful when it came to such a difficult, seemingly far-off task as putting a man on the moon. Acknowledging the intimidating goal, he assured the audience, and America at large, that the American people could take on such tasks, stating,

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard."

~ President John F. Kennedy's Address at Rice University on the Nation's Space Effort, September 12, 1962

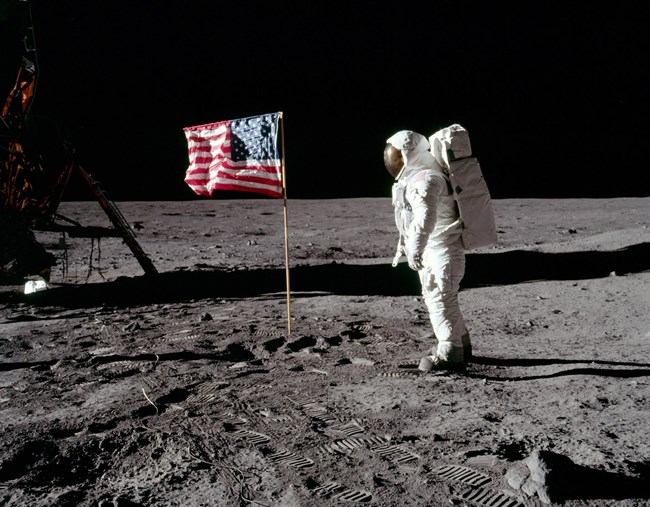

His appeal reached the hearts of many. Americans remained mostly in support of the Moonshot until the successful landing of Apollo 11 on the moon on July 20, 1969. 500 million people around the globe watch the moon landing on television. Though John F. Kennedy did not live to see the landing, his work and legacy remained strong in its success and the inspiration behind it.

A National Effort: Concerns and Controversy

Though the Apollo 11 Mission, and the Space Race as a whole, were seen by many as great triumphs for science, the nation, and humanity, they were not without protest or concern. The involvement of rocket scientist Wernher Von Braun in much of NASA’s research, development, and missions was very controversial. Von Braun had been an active member of the Nazi Party, and weapons researcher, in Germany during World War II. He had been recruited by the United States initially to work on missiles and was later given a high position at the newly formed NASA.

Additionally, some feared the great investment of federal money and resources into spacefaring technology was coming at the cost of other national expenditures and Americans in need. The day before the Apollo 11 launch, Ralph Abernathy, leader of the Poor People’s Campaign, led hundreds of demonstrators to advocate for aid to Americans facing hunger and poverty. Some noted a lack of diversity among astronauts and in the Space Race as a whole. President Kennedy received multiple letters imploring him to include qualified people in the Space Race regardless of their race, gender, or sexual orientation. President Kennedy was heavily involved in both civil rights and space exploration, but the two would not come together under his administration.

NASA

Legacy: Much More Than One Man

With his assassination on November 22, 1963, Kennedy would leave behind the groundwork for what he could not complete in his lifetime. In his absence, his legacy persisted. The effects of Kennedy’s work to support space exploration are ongoing. NASA continued moon missions into the 1970s, and space exploration continues to this day. The Space Race led to a renewed interest in science and math education, contributing to what we know today as a focus on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Many essential modern technologies, including forms of water purification, integrated circuits, and fireproof materials, have their origins in the Apollo missions. During the tense Cold War, the moon landing gave people something to work toward, a goal for which humanity could strive toward and celebrate. Today, President Kennedy’s legacy in the Moonshot is honored with NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center, named for him by President Lyndon B. Johnson on November 29, 1963, just a week after Kennedy’s assassination. His legacy can also be seen in the world’s investment in space as a new, collaborative frontier.

Conclusion

The moon landing remains one of humanity’s greatest scientific achievements. Throughout his presidency, John F. Kennedy’s ongoing efforts to organize the necessary resources and rally support for the highly ambitious mission were essential to the mission’s development and success. As President Kennedy became more involved in the Space Race, he brought the United States along with him.

“... it will not be one man going to the moon—if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.”