Last updated: February 12, 2025

Article

Lake Glen: A Black Country Club in Cuyahoga Valley

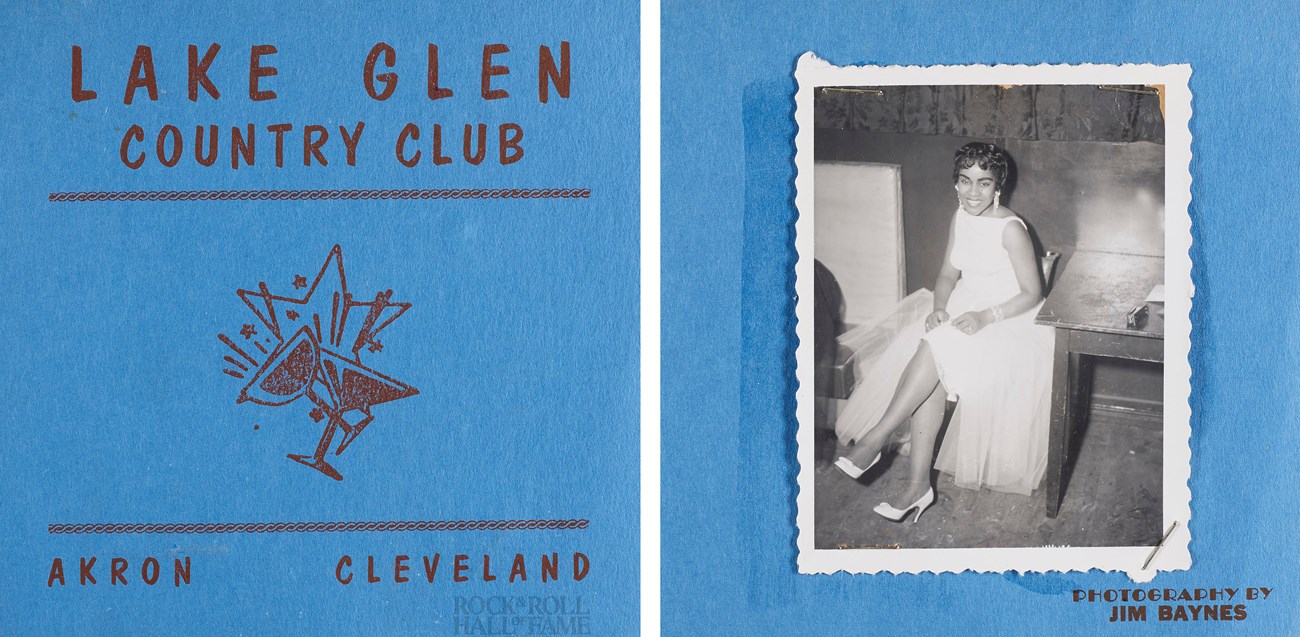

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame/Jimmy Baynes Collection

About six million African Americans migrated to cities in the North, Midwest, and West in the decades after the mid-1910s. They fled Jim Crow Laws and threats of racial violence in the South. They wanted greater social, economic, and political freedom. Some newcomers started businesses of their own. One of these was Lake Glen Country Club, on the eastern rim of Cuyahoga Valley. It was located at 4572 Akron Cleveland Road, about 26 miles from Cleveland and 11 miles from Akron. Visitors came from as far as Erie, Pennsylvania, to enjoy Lake Glen’s music, food, comedy, dance, and drag performances. The club operated under three names from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Consider where you feel the safest to express yourself. Lake Glen was a “black-and-tan club.” This slang term, originating in the 1920s, meant the club catered to Black, White, and mixed-race clientele. Historian Kevin Mumford refers to these places as “interzones” where people could explore interracial and queer sexualities, and discuss taboo subjects. In Lake Glen's time, these topics included Black consciousness, feminism, and other ideas that shaped the civil rights movement. Although such businesses were often met with racism and discrimination, patrons showed resilience and expressed joy. Lake Glen served as refuge for its primarily Black but integrated audience by providing entertainment, leisure, and relaxation.

This research is part of Green Book Cleveland, a collaborative project documenting Black history in Northeast Ohio. The Green Book was a Black motorist guidebook published from 1936–66. Understanding sites supporting Black travel and recreation is a priority of the African American Civil Rights Network.

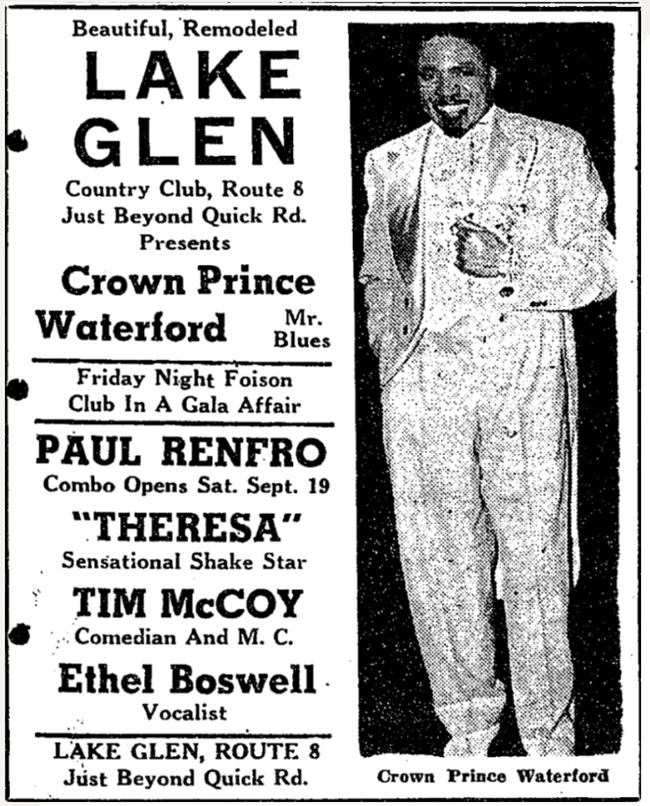

Cleveland Public Library/Cleveland Call & Post

Crown Prince Waterford, the Resident Performer

Charles “Crown Prince” Waterford (1916–2007) was an accomplished blues singer who recorded for many labels including Aladdin, Capitol, and MGM. Waterford was born in Jonesboro, Arkansas. He was a graduate of the prestigious Tuskegee Institute and served in the US Army during World War II. A 1957 Cleveland Call & Post article noted: “Waterford comes from a musical family. His father, Evan T. Waterford was a member of the Wilberforce glee club. His mother was a pianist and organist. Two sisters, Mrs. Annie Lee Moss and Mrs. Lois Thorton sang with the original Wings Over Jordan Choir and toured the world with that famous organization. A third sister, Evanna Cotten, is a night club pianist who a few years ago was highly popular with patrons of the better clubs in Cleveland.” The article also mentions that his father was in the first graduating class of the historic Wilberforce University in Ohio.

Waterford got his start with Jay McShann’s band in 1944. His roommate on their nationwide tours was the legendary “Yard Bird,” Charlie Parker. Waterford also played in the famous swing band Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy. In 1946, he became a national solo act, best known for playing at lavish West Coast night clubs. His band became an incubator for talent such as bass player Oscar Pettiford. Pettiford was an innovator of the revolutionary jazz style called bebop and later performed with the world-famous Duke Ellington. Waterford’s band also provided a start for a young Charlie Christian. Christian is credited with being one of the first electric guitar players and a pioneer of what is now called lead guitar.

Throughout the 1950s, Crown Prince Waterford was the most advertised performer at Lake Glen. The 1957 Cleveland Call & Post article went on to say: “Strong voiced, six feet-three and amply muscled, Waterford is rated among the top blues men of the nation. . . . without much doubt has the sharpest wardrobe of costumes owned by any of the blues shouting fraternity. . . . He is at Lake Glen now in an indefinite engagement. He works hard, he does . . . And we guess he earns his relaxation and his rest in his automobile . . . We mean his Cadillac.”

Cleveland Public Library/Cleveland Call & Post

Police Raids and Resistance

Anti-vice campaigns swept the US during the 1950s. Newspaper articles describe “frequent” raids at Lake Glen and the nearby Cabin Club by Summit County police and health inspectors. The clubs were cited for bootlegging, expired liquor licenses, gambling, and unsanitary conditions. The Cleveland Call and Post reported attendees being roughed up and arrested. These raids peaked in 1957 when C. William O’Neill became Ohio’s new governor. O’Neill pushed county agencies to crack down on “organized commercial gambling and vice.” Black businesses were treated more severely than White ones. At Lake Glen, club-goers maintained that frequent police raids were due to deliberate racism and resentment towards its integrated audience. This view is consistent with Green Book research by historians such as Candacy Taylor. Lake Glen was on the edge of Cuyahoga Falls. The community is now racially integrated, but historically was considered a “sundown town.”

A March 1957 Cleveland Call & Post article titled “Interracial Patronage Causes Harassment” painted a vivid picture. It quoted Booker T. Brooks, a Lake Glen manager, as saying “Members from the Sheriff’s office have been coming into the club, flashing lights into customer’s eyes, even during the show, grabbing glasses off tables smelling them, insulting our white customers, particularly women, demanding to know why they do not go to white business establishments in the area instead . . . There definitely appears to be a concerted effort to antagonize our customers, run them away, ruin our business and force us to close by imposing unnecessary fees and assessments.” When asked to respond to Brooks’ comments, Sheriff Russell Byrd responded, “We have not been discriminating against anybody. I don’t believe in discrimination. There are certain conditions existing at Lake Glen that must be straightened out and we intend to see that they are.” One observer quipped, “Somebody ought to tell the new sheriff he’s warming over the same old soup.” The Cleveland Call & Post concluded that “Sheriff Bird resorted to the age-old ruse of numerous police organizations of building up their reputations and records by staging a shakedown among negro citizens.” In contrast, raid coverage by the mainstream Akron Beacon Journal focused more on criminality.

Booker T. Brooks, Sr. was prominent in the Akron music scene. When he died in 1971, the Cleveland Call & Post wrote “Mr. Brooks, 67, will be remembered by thousands as a promotor of public dances in the old East Market Street Gardens. In the late 1920s and early 1930s when such bands as Cab Calloway, Zach White and Chick Webb were at the height of their popularity, he brought the best of them to the Gardens. People from all northern Ohio attended.” In addition to his role as manager, Brooks was a promoter for Lake Glen and owned several Akron clubs.

Changing Owners and Names

The property histories of businesses that served Black communities before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 can be confusing. From newspaper accounts, we understood that Lake Glen was owned by Irvin Clark Robinson of Akron from 1952–60. However, we have not found any documents to back this up in the Summit County, Ohio, records. Sometimes Black businesspeople needed to obscure their roles in the face of discriminatory practices. We don’t know if this was the situation here.

Here is what we found. In 1950, Ray and Rita Gibson purchased the 13-acre tract in Northampton where Lake Glen was (or was to be) located. Six months later, the Gibsons sold the property to the Wadsworth Equipment Company. Samuel Laughlin (who purchased and sold countless Akron properties from 1935–1960) bought it in 1953. In 1959, Laughlin sold the property to Lake Glen Country Club, Inc., in which Luther White was president and his brother “Henston” White served as secretary. Newspaper accounts said that Luther and “Heston” White bought Lake Glen with financing from the Teamsters Union. The brothers added a motel and changed the name to the Fountain Blue. It appears that they lost ownership when they couldn’t pay their Teamsters Union mortgage. Summit County records show the property being transferred only six months later to the Central States SE & SW Area Pension Funds. In 1963, Lake Glen Country Club was put up for public sale at the Akron Court House and sold to the highest bidder, Northampton Motel, from Parma, Ohio.

The club met its demise in 1964 when it burned to the ground in a massive fire of an undetermined cause. A short time later, the SaSa Lounge opened on the same property. It also catered to a Black audience, according to an oral history with local resident Bob Bard. The SaSa Lounge was advertised as late as 1971.

Learn More

Additional Lake Glen research is on the Green Book Cleveland website. It compares raid reporting by the Akron Beacon Journal and the Cleveland Call & Post. We thank Summit Metro Parks for assisting with this research. The site also has articles about the nearby Cabin Club / Drift Inn and Stonibrook. For national context, read Candacy Taylor’s book Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America.

Learn more about similar jazz clubs in Jazz Arrives in Northeast Ohio. For a deeper dive into the political and cultural history of jazz clubs, we recommend John Lowney’s book Jazz Internationalism: Literary Afro-Modernism and the Cultural Politics of Black Music. Historians Kevin Mumford and Chad Heap research issues of race and sexuality in mid-1900s Black nightclubs.