Last updated: April 22, 2025

Article

“Can This Flesh Belong to Any Man...?”: George and Rebecca Latimer’s Flight to Freedom

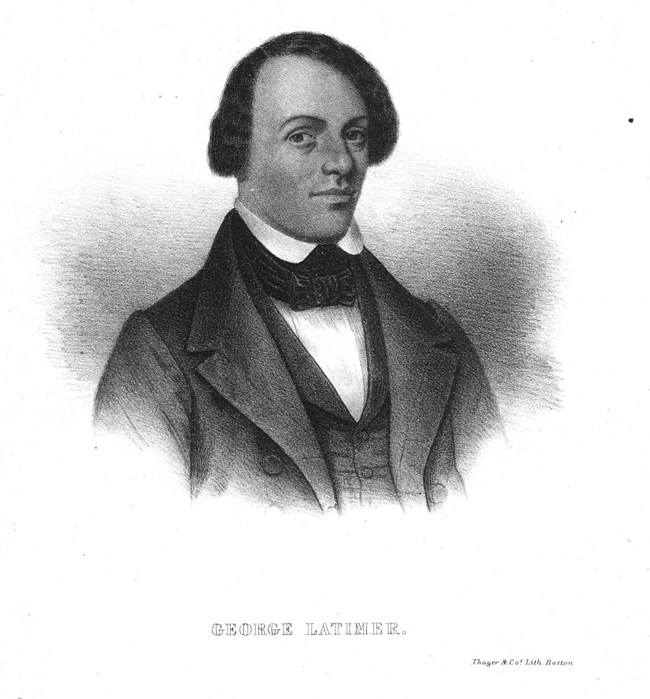

In 1842, freedom seekers George and Rebecca Latimer arrived in Boston after escaping slavery in Virginia. Authorities soon arrested George, igniting a storm of antislavery protests, while Rebecca remained safely hidden away in the homes of local abolitionists.

Though Bostonians quickly secured George's freedom, the Latimer case provided antislavery activists the political capital to usher in a statewide Personal Liberty Law. This "Latimer Law" intended to thwart future attempts by enslavers and their agents to recapture freedom seekers.

Once legally free, the Latimers established themselves and their growing family in Boston and the surrounding areas.

When George later fell afoul of the law and served time in prison, the family broke up and scattered. Rebecca worked in Boston before ultimately relocating to New York, while George lived the rest of his life in Lynn, just outside of Boston.

Though largely remembered for the law that bears their name, the Latimers' story also provides a powerful lesson of family resilience, community protest, and social change.

Stop 1 — 1820-1842, Norfolk, Virginia Show on map

Henry Howe's "Historical Collections of Virginia" (1845)

Born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia, George Latimer claimed July 4, 1820, as his birthday though the exact date is unknown. His father’s brother enslaved him and his mother, Margaret Olmsted. As a teenager and young adult, Latimer faced abuse from multiple enslavers. Around 1840, he attempted an escape to freedom. However, he only made it to Baltimore before being captured and returned to slavery.[1]

Born on September 18, 1824, Rebecca Smith also grew up enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia.[2] Little else is known about her early life.

George and Rebecca married in February 1842. Expecting their first child, the couple did not want to raise their family in slavery. George recalled:

On 4th last month [October] I started to run away again with my wife. I had been saving for some time… I have thought frequently of running away even when I was a little boy. I have frequently rolled up my sleeve, and asked—'Can this flesh belong to any man as horses do?'[3]

For themselves and their future children, the Latimers made the risky decision to leave Virginia and go north.

Stop 2 — October 4-7, 1842, Frenchtown, Maryland Show on map

On October 4, 1842, George and Rebecca escaped Norfolk by stowing away on a steamship. Hiding in the hold of the ship, the couple landed in Frenchtown, Maryland.[4] George recounted:

With my wife, also a slave, I secreted myself under the forepeak of the vessel, we lying on the stone ballast in the darkness for nine weary hours. As we lay concealed in the darkness, we could look through the cracks of the partition into the bar-room of the vessel, where men who would have gladly captured us were drinking.[5]

New York Public Library

Once in Frenchtown, George, whose light-skin allowed him to pass as white person, purchased a first-class ticket for himself and Rebecca, who pretended to be his servant. They headed to Philadelphia and then to Boston.

George remembered an early close call as they boarded the northbound ship:

When we went aboard the vessel at Frenchtown a man stood in the gangway who was a wholesaler of liquors. He knew me, for my master kept a saloon and was his customer. But I pulled my Quaker hat over my eyes and passed him unrecognized. I had purchased a first-class passage and at once went into the cabin and stayed there. Fortunately he did not enter. From Baltimore to Philadelphia I travelled as a gentleman, with my wife as a servant.[6]

The Latimers arrived in Boston on October 7, 1842, and introduced themselves to local abolitionists as freedom seekers from Virginia.[7] For further protection, George began to use an alias—Albert Mason.[8]

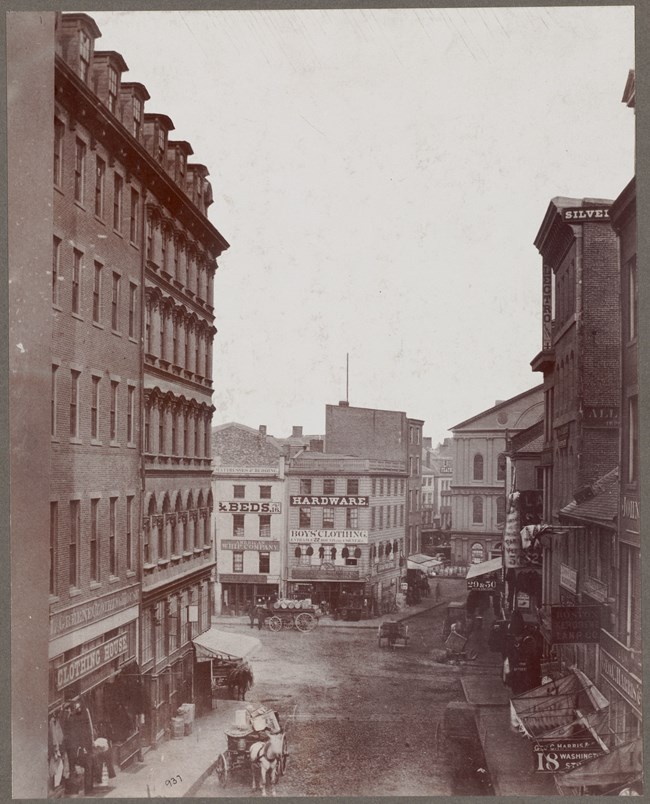

Stop 3 — October 18, 1842, Dock Square, Boston Show on map

Boston Public Library

Just days after the Latimers arrived in Boston, William Carpenter, an associate of George’s enslaver, James Gray, recognized George in the city. He notified Gray, who quickly arrived in Boston to have George Latimer arrested. Gray accused Latimer of stealing money and goods from his store, making Latimer a "fugitive from justice." Charging him for larceny, rather than for seeking freedom from his enslavement, allowed authorities to arrest George more easily. Black abolitionists in Boston viewed the charge of theft against George as "only a fetch on the part of the owner."[9]

Police arrested George in Dock Square on October 18, 1842.[10] Officers initially detained him at the Police Court on Court Street.

Stop 4 — October 20, 1842, Leverett Street JailShow on map

On October 20, a crowd of more than 300 Black abolitionists, mostly men, arrived outside the Police Court in an attempt to rescue Latimer. However, police escorted George out a back door, trying to avoid a confrontation with the crowd.

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

As police brought George to the Leverett Street Jail in Boston's West End, "a considerable number" of Black citizens followed them "carrying sticks and stones" and "uttered general threats" towards his captors. [11]

John L. Brent, James Scott, William H. Jackson, Joseph Johnson, and James Jackson all received fines of $3 for their disorderly behavior that night.[12] Police arrested other men and women for "resisting and obstructing" officers as they took Latimer to the Leverett Street Jail. These included Robert Wood, a member and secretary of the New England Freedom Association, a Black organization that assisted freedom seekers. Others arrested included Henry G. Tracey, Francis Saunders, Hamilton H. Smith, Thomas Prior, Henry Holt, Talbot Thompson, Solomon Guess, Lucida Lawes, and Clarissa Webb. [13]

The police even arrested people in the vicinity who did not participate in the rescue attempts. For example, they arrested William Parrish, a resident of Cambridge. The Boston Post reported that "the simple fact of being seen about the diggings was enough to authorize his arrest," but at court, "the traverse jury, however, were of a different way of thinking" and "returned a verdict of 'not guilty.'"[14]

Despite their efforts being viewed "riotously and routously" by authorities, Black men and women in Boston took direct action in an unsuccessful attempt to rescue Latimer.

Stop 5 — October-November 1842, High Street, BostonShow on map

Massachusetts Historical Society

As the authorities detained George at the Leverett Street Jail, Rebecca, while pregnant, evaded capture by hiding at a local safe house. Though Rebecca's enslaver, Mary Saver, put out a runaway ad[15] for her, she safely stayed at "the house of friendly abolitionists on High Street."[16]

While the exact house where Rebecca stayed remains unknown, several abolitionists lived on High Street at that time who may have sheltered her. For example, Joseph and Thankful Southwick lived at 4 High Street.[17] In 1842, Thankful served as the president of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Her husband, Joseph, served the treasurer of the first Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization established in 1841 to assist freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad.[18] Rebecca's safety depended upon the strong network of abolitionists in the city.

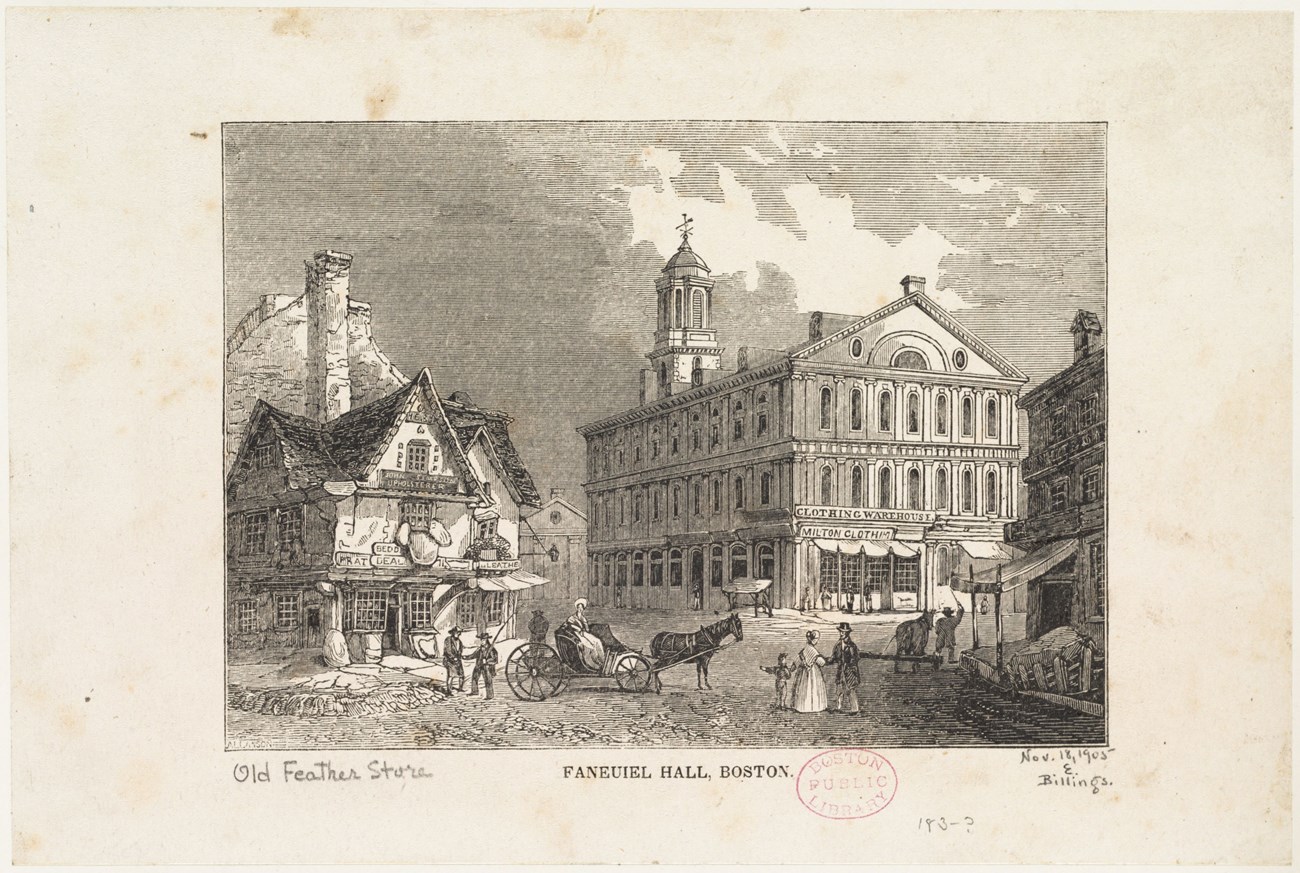

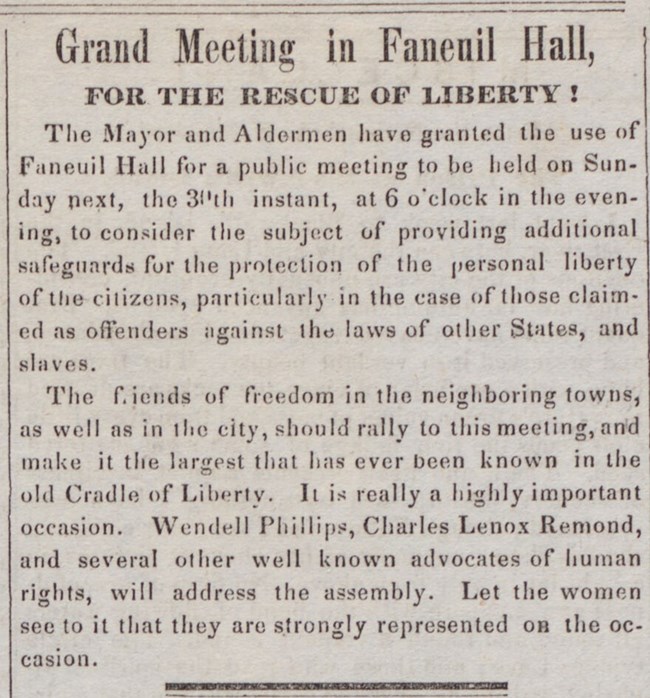

Stop 6 — October 30, 1842, Faneuil Hall, BostonShow on map

In addition to the unsuccessful attempt to rescue Latimer from the jail, Bostonians quickly organized to help him gain freedom. They formed the "Latimer Committee" and published The Latimer Journal and North Star to rouse antislavery sentiment and action. Edited by Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, William Francis Channing and Frederick S. Cabot, the paper ran from November 11, 1842, to May 16, 1843.[19]

The journal emphasized:

These things can no longer be done in a corner. If Boston is to be made the scene of this dirty work, at least, all the world shall know it. Its infamy shall be written in glaring letters.[20]

While Samuel Sewall, Amos B. Merrill, and Charles M. Ellis served as counsel for George in court, others held "Latimer Meetings" for him across the state. In Boston, Faneuil Hall and the Marlboro Street Church served as critical venues for such rallies.[21]

Boston Public Library

At the October 30 Latimer meeting at Faneuil Hall, both Charles L. Remond and Frederick Douglass attempted to speak. However, anti-abolitionists disrupted the meeting. Later, the Latimer Committee published resolves in the Latimer Journal about the incident, invoking the revolutionary legacies of Faneuil Hall:

Boston Public Library

Resolved, That the riotous conduct of those persons who disturbed the meeting held in Faneuil Hall, on the 30th ultimo, called ‘to concert measures for preserving liberty, and to provide additional safeguards for the protection of those claimed as fugitives from other States, or as slaves,’ was disgraceful to the city of Boston, a desecration of the ‘Cradle of Liberty,’ and should be severely rebuked by all who love freedom and equal rights.[22]

The abolitionists refused to allow "a freeman seized in [their] midst."[23] The case against Latimer questioned the liberty of all free persons in Massachusetts and the North. They feared, "Any man amongst us may be seized and carried off without trial," now that "our laws have been abused, desecrated by being used for base ends." A blatant "abuse of law" would not be tolerated by those in the Cradle of Liberty and "within sight of Bunker Hill."[24]

In his first public letter published in the abolitionist newspaper the Liberator, Frederick Douglass wrote to William Lloyd Garrison about the Latimer case:

And all this is done in Boston—liberty-loving, slavery-hating Boston—intellectual, moral, and religious Boston. And why was this—what crime had George Latimer committed? He had committed the crime of availing himself of his natural rights, in defence of which the founders of this very Boston enveloped her in midnight darkness, with the smoke from their thundering artillery.[25]

Stop 7 — November 17-18, 1842, Court House, BostonShow on map

Boston Public Library

George refused to be re-enslaved by Gray and sent back to Virginia. He told his attorney Amos B. Merrill:

I would rather die than go back. Gray has just been here, trying to get me to say that I will go back willingly. I turned my back on him, and would not speak to him. He said I would go back peaceably, there should be no more trouble—he would take me out of jail, and use me well. I then turned towards him and said, ‘Mr. Gray, when you get me back to Norfolk you may kill me.’[26]

Despite abolitionist organizing and the efforts of lawyers Merrill and Sewall, the court ordered Latimer back to Gray.

However, Amos B. Merrill and Charles M. Ellis, who also represented the people arrested for the "riot about the Court house," attained a Court order for George to testify at their trials. Rather than repeatedly move George from jail to the courthouse, at the risk of other attempted rescues, his jailers stated that once they released him they would not take him back into custody. With crowds continuing to surround the jail, the sheriff encouraged Gray to accept a sum of money from abolitionists to purchase George’s freedom.[27]

At first, Gray asked for $1500 like a "cunning villain."[28] An unnamed Black man and then Henry Ingersoll Bowditch offered to purchase Latimer’s freedom for a lesser sum. But upon hearing that Latimer would be released from jail the next day to testify, Bowditch and others knew that Latimer would be instantly rescued by abolitionists and therefore they refused to pay for his freedom. The night before the sheriff released Latimer, Gray quickly agreed to sell George's freedom for $400 dollars to Reverend Nathaniel Colver and soon left the city.[29]

Rebecca's enslaver, Mary Saver, quickly dropped the charges against her following the abolitionist uproar caused by George's imprisonment.

Though the law mandated George Latimer be returned to Gray, Boston's vigilant abolitionist community protected his freedom by purchasing it from his enslaver. To secure the future freedom of others, however, required larger political change.

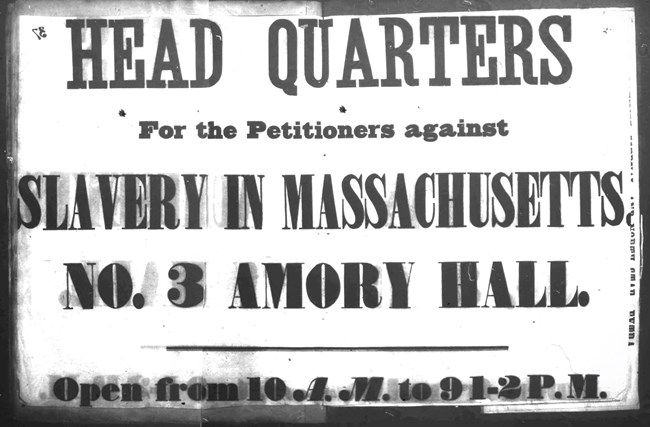

Stop 8 — December 1842-March 1843, 3 Armory Hall, BostonShow on map

Massachusetts Historical Society

Though Bostonians quickly purchased Latimer's freedom, his case galvanized the abolitionist community of Massachusetts into further political action. To enshrine personal protections in the state, they advocated for the Personal Liberty Act.[30] The law would prevent authorities in Massachusetts from assisting slave catchers and holding freedom seekers in state, county, or city and town buildings.[31]

To gain support for this law, George Latimer attended and spoke at antislavery rallies with Frederick Douglass and Charles Lenox Remond in Boston and other places such as Essex, Hingham, and Salem.[32]

Though Latimer effectively used his story and renown to motivate people to support the Personal Liberty Law, some expressed concern of how organizers used him at these events. For example, the New Bedford Bulletin wrote:

They are exhibiting the slave Latimer at the fair of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery society to add to its attractions. They will probably ruin him before they have done with him. He had better make the best of his way to Canada, and when there set himself to work for a living. We rejoice at his freedom, but regret to see him made a lion, alias a fool of.[33]

Stop 9 — March 24, 1843, Massachusetts State HouseShow on map

Massachusetts State Archives courtesy of Widener Library at Harvard University

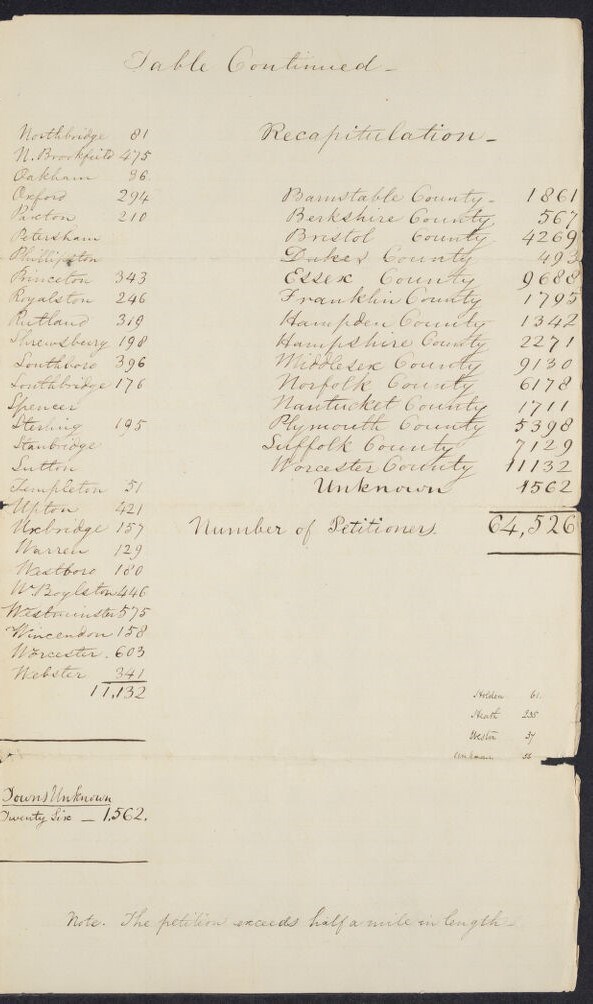

As a result of dedicated campaigning and rallies throughout the state, antislavery activists garnered 64,526 signatures for the petition calling for the passage of the Personal Liberty Act.[34]

Enacted by the state legislature and more commonly known as the "Latimer Law," the Personal Liberty Act "forbade Massachusetts officials or facilities from being used in the apprehension of fugitive slaves and represented a major victory for the abolitionists."[35] Governor Marcus Morton approved the Act and it became law on March 24, 1843.[36] Massachusetts' "Latimer Law" became the basis for many similar Personal Liberty Laws in other states in the coming years.

Stop 10 — 1848, 7 Shawmut Ave, Chelsea, MassachusettsShow on map

Massachusetts Historical Society

In the years following the passage of the Personal Liberty Act, George and Rebecca Latimer expanded their family. George secured employment first as a barber and then later as a paper hanger. The family moved frequently, settling in Lynn and then Chelsea. While in Chelsea, Rebecca gave birth to their youngest child, Lewis, in 1848. Together, she and George had four children—Margaret, George, William, and Lewis.[37]

Stop 11 — 1851-1855, 10 Oswego Street, BostonShow on map

By 1850, the Latimer family had moved back to Boston. They resided at 10 Oswego Street in the South End. Despite George’s employment, however, the family continued to struggle financially.

Fortunately, they received some financial help from the 1850 Boston Vigilance Committee, the third and final vigilance committee in Boston formed in response to the Fugitive Slave Law.

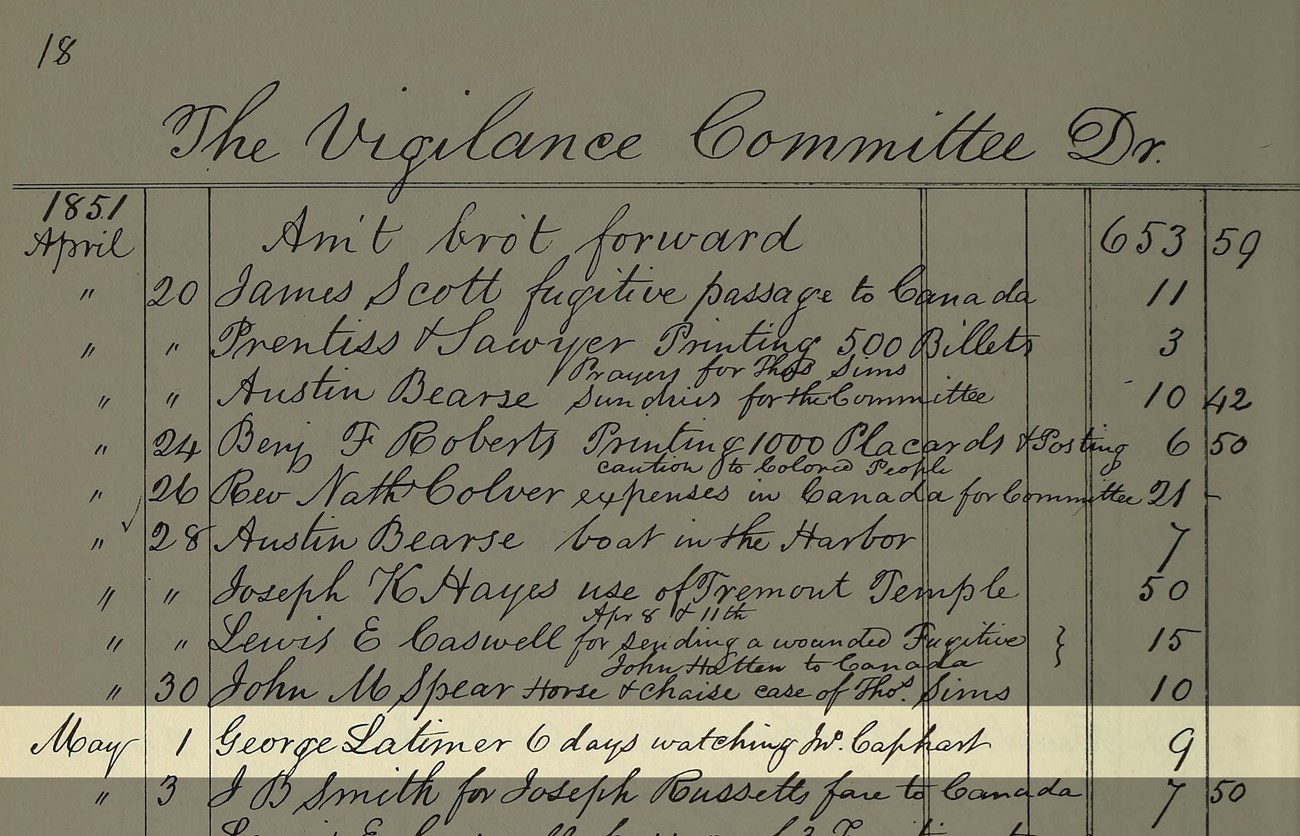

W. B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives

For example, in May 1851, the Vigilance Committee paid George Latimer for “watching” John Caphart, a known slave catcher from Norfolk, Virginia, over six days. Caphart had played a prominent role in the unsuccessful rendition of freedom seeker Shadrach Minkins several months prior. Just as he had been protected by Bostonians almost a decade earlier, George kept a watchful eye on the slave catcher as he made his way through the city.[38]

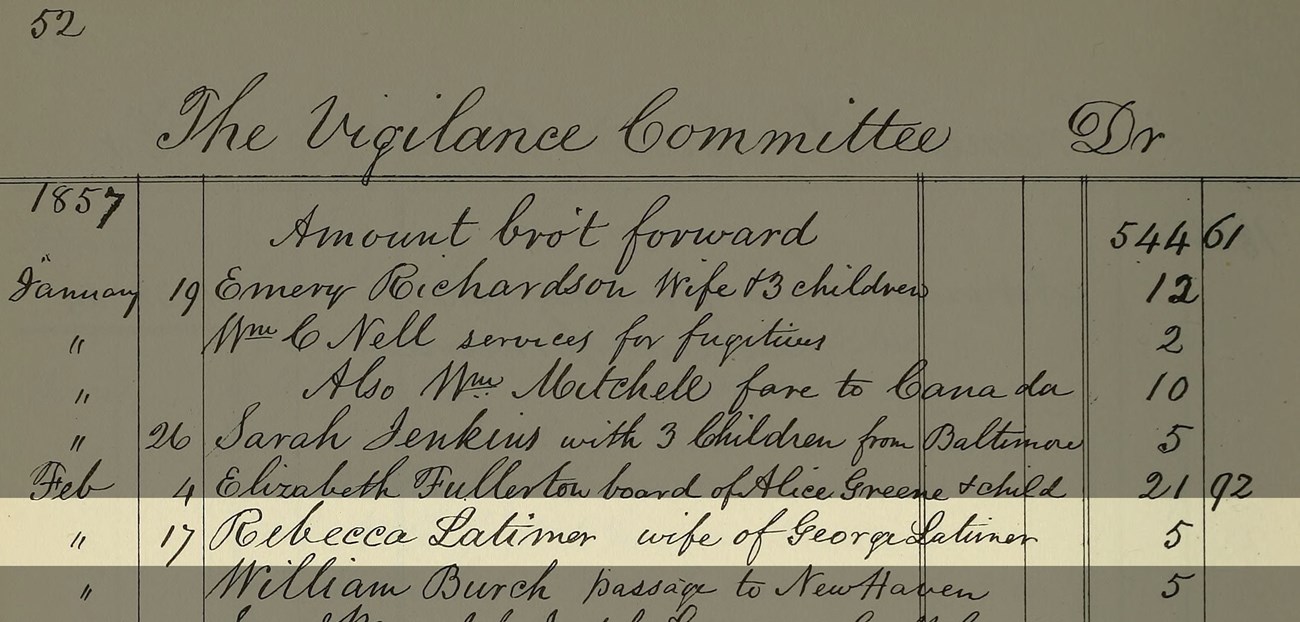

W. B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives

Stop 12 — December 23, 1857, Charlestown State PrisonShow on map

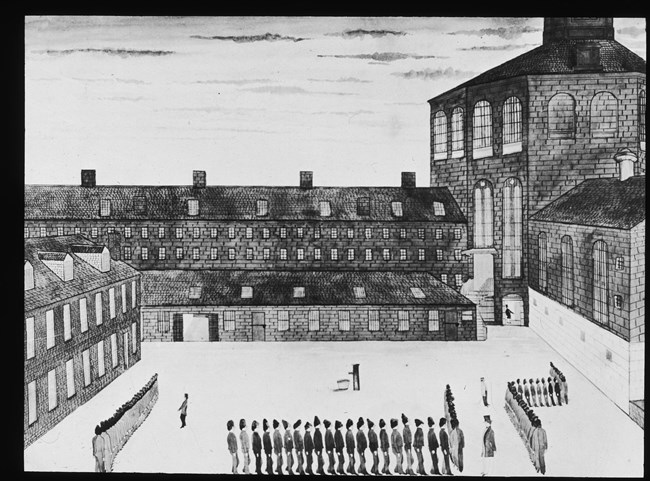

Boston Public Library

On January 17, 1854, George Latimer stole a pocketbook containing money from Thomas Townsend. The court found George guilty, and the judge sentenced him to spend more than a year in prison, with six months hard labor at the Middlesex State Prison.[40]

Frederick Douglass, in his newspaper Frederick Douglass' Paper, published notice of George’s arrest, commenting on his behavior:

George Latimer, formerly a slave, for whom there was much sympathy manifested a few years since, has shown himself unworthy the confidence of those who assisted him…The prisoner has for a longtime borne a bad reputation.[41]

A few years later, police arrested George again, this time, for breaking into the store of Ephraim H. Low in December 1857. The court sentenced him to 5 years in State Prison, with two days solitary confinement and hard labor. They imprisoned him in the Charlestown State Prison.[42]

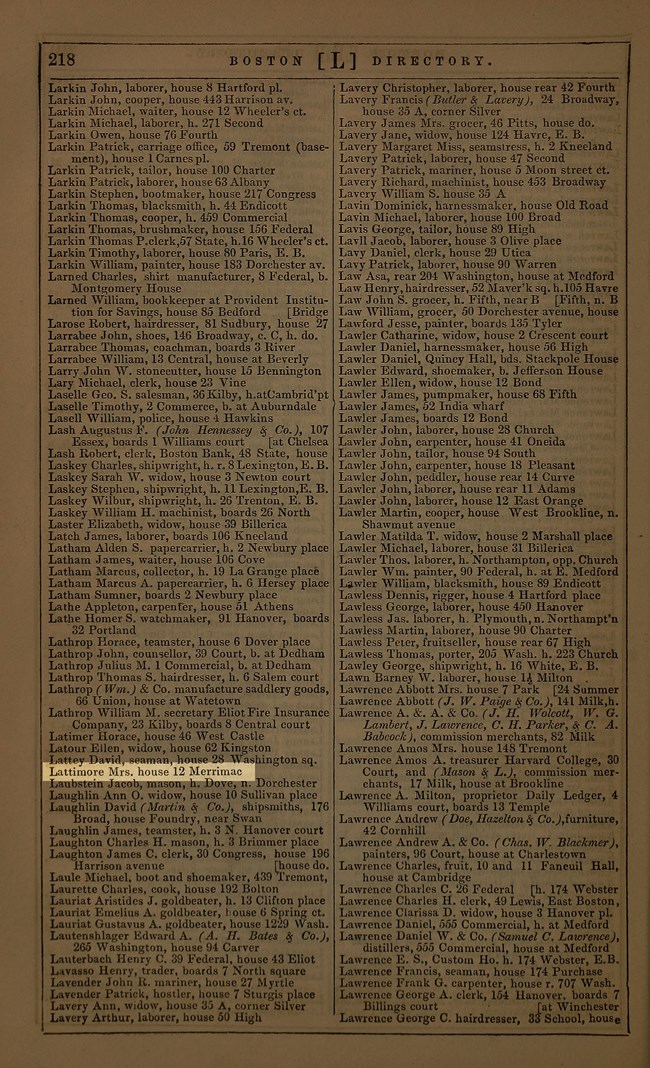

Stop 13 — 1858-1860, 12 Merrimac Street, BostonShow on map

Boston Public Library

As a result of George’s imprisonment, Rebecca Latimer lived alone with their daughter Margaret and son Lewis. The absence of George’s income forced Rebecca to send her two oldest sons, George and William, to live at the Tewksbury.[43] Following their time at the almshouse, the two became apprentices elsewhere; William worked as a waiter in Springfield and George on a farm. Margaret eventually moved out and lived in the household of a friend, Samuel F. Bennett, and worked as a domestic servant.[44]

In 1858, Rebecca lived in the West End neighborhood in Boston at 12 Merrimac Street. Her son Lewis attended the Phillips Grammar School, which had been desegregated in 1855. Because of their dire financial situation, however, Lewis needed to work which greatly affected his attendance. He worked numerous jobs as a young boy, even selling copies of William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, the Liberator.[45]

Rebecca found employment as well. In 1860, she worked as a servant and did her best to provide for her children.[46]

Stop 14 — 1863-1865, 107 Cambridge Street, BostonShow on map

In his diary, Lewis Latimer recalled that he "remained in his mother's home until she got a chance to go to sea as a stewardess."[47] Working at sea likely played a role in Rebecca Latimer’s second marriage. In 1860, she married Oscar Freeman, a Black mariner from Maine. Together, they likely spent most of their time at sea, away from Boston. By 1865, they both boarded in the household of Mark A. DeBank, another Black mariner, on Cambridge Street.[48]

Library of Congress

During this time, George and Rebecca’s children moved beyond Boston. By 1864, all three sons—George, William, and Lewis—had enlisted to fight for the United States in the Civil War. In 1863, George enlisted in the 29th Connecticut Infantry, an all-Black regiment.[49] William and Lewis both enlisted in the Navy.[50] All three of their sons bravely served their country and survived the war.

Stop 15 — 1865-1868, 69 Phillips Street, BostonShow on map

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

After the Civil War, in 1868, brothers George and William, as well as Oscar Freeman, lived in the rear of 69 Phillips Street. While no household locations for Lewis and Rebecca are listed in the 1868 Boston City Directory, it is likely that they too lived at 69 Phillips Street. Lewis wrote in his diary that he and his mother "went into housekeeping in a couple of rooms on Phillips Street," after she returned to Boston from sea.[51]

Home to Lewis and Harriet Hayden, the Twelfth Baptist Church, and other key sites, Phillips Street, formerly known as Southac Street, once served as a stronghold of Boston’s Underground Railroad. On Phillips Street, Rebecca Latimer lived alongside those who, like herself, had escaped slavery, as well as those who helped them when they arrived in Boston.

George’s time in prison separated him from his family. After his release, he returned to work as a paperhanger in Boston and later Lynn. George ultimately remarried to Charlotte Saunders in 1865.[52] Charlotte gave birth to their son, Charles, a few years later.[53]

Stop 16 — 1880s, Bridgeport, Connecticut (Rebecca) and Lynn, Massachusetts (George)Show Rebecca's location on mapShow George's location on map

By 1880, Rebecca had moved to Connecticut to be near her children. However, she and her second husband, Oscar, no longer lived together—instead, she lived with her son Lewis as a divorcee while Oscar remained in Boston.[54]

With growing success as a patent draftsman, Lewis Latimer relocated to Bridgeport to work for the United States Electric Lighting Company. Having previously worked with Alexander Graham Bell on drafts of the telephone, he then patented carbon filaments for the lightbulb.[55]

Rebecca’s other children also lived in Connecticut; Margaret and William in Bridgeport, and George in Hartford.[56]

While Rebecca and her children moved away from Massachusetts, George continued to work and live in Lynn. After his second wife Charlotte passed, he married for a third and final time in 1884, to Mary Williams.[57] He also became involved in the Odd Fellows, a benevolent fraternal order.[58]

Stop 17 — 1894-1910, Flushing, New York (Rebecca) and Lynn, Massachusetts (George)Show Rebecca's location on mapShow George's location on map

Late in his life, George Latimer retold the story of his and Rebecca's escape from slavery as part of the Story of the Hutchinsons. George had previously traveled with the Hutchinson Family Singers, an abolitionist music troupe, for various antislavery events in the early 1840s.[59] He gave minimal details on his life after 1843, explaining, "For forty-five years I pursued the trade of a paperhanger in Lynn."[60]

Frederick Douglass wrote to Lewis Latimer about seeing his father, George, in 1894:

I give you thanks for your excellent letter. It made me proud of you. I was glad to hear of your mother and family. I saw your father for a Moment in Boston, last spring. He seemed in good health then and I am surprised to learn of his condition now. It is fifty- two years since I first saw your father and mother in Boston. You can hardly imagine the excitement the attempts to recapture them caused in Boston. It was a new experience for the Abolitionists and they improved it to the full extent of which it was capable.[61]

In 1895, George suffered from a fall. With his health slowly in decline, he died from a stroke in Lynn, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1896.[62]

Lewis Latimer House Museum

Rebecca remained close to her children throughout her life. She lived with them in Connecticut, then later moved to Flushing, New York, with her son Lewis. She died at 86 years old in Flushing on August 13, 1910. Her remains are interred at Old North Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.[63]

Her obituary remembered her as "one of the oldest and highest respected residents in Flushing." It made no mention of her and George’s escape to freedom but did highlight the Civil War service of her three sons.[64]

The Latimer case, and the law that bears their name, illustrated the growing strength of interracial alliances in the fight against slavery and served as an important precursor for the battles yet to come.

Their personal lives and actions–including George and Rebecca's flight from slavery, their experiences in freedom, and their sons’ service in the Civil War and beyond–show powerful stories of family resilience, struggle, and service as well as the complexities and uncertainties of life in the North.

Footnotes

[1] Asa J. Davis, “The George Latimer Case,” The George Latimer Case ; Latimer Journal and North Star, November 23, 1842, 3.

[2] New York Age, August, 25, 1910, 2.

[3] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 23, 1842, 3.

[4] Boston Globe, June 2, 1896, 12. ; Scott Gac, “Slave or Free? White or Black? The Representation of George Latimer,” The New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015): 75, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718203.

[5] Glennette Tilley Turner, Lewis Howard Latimer, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991), 8-9, Archive.org.; Story of the Hutchinsons (Tribe of Jesse) Volume 2, (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1896), 350-351, Archive.org.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Boston Post, October 20, 1842, 2.

[8] Boston Post, October 20, 1842, 2.

[9] Boston Post, October 20, 1842, 2; Boston Post, November 1, 1842, 2.

[10] Boston Post, October 20, 1842, 2; Boston Post, October 21, 1842, 2; Boston Post, November 1, 1842, 2.

[11] Boston Post, October 21, 1842, 2

[12] Boston Post, October 21, 1842, 2

[13] Boston Post, November 14, 1842, 1-2; Theron Metcalf, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1858), 536-553.

[14] Boston Post, November 24, 1842, 2.

[15] Ad transcription from Latimer Journal: “THE LATIMERS. The Slaveholders account of this interesting family. ‘American Beacon,’ Norfolk, VA. Oct. 15. $50 REWARD. Ran away from the subscriber last evening, negro woman Rebecca, in company (as is supposed) with her husband, George Latimer, belonging to Mr. James B. Gray of this place. She is about 20 years of age. dark mulatto or copper colored, good countenance, bland voice, and self-possessed, and easy in her manners when addressed. She was married in February last, and in at this time obviously enceinte. She will in all probability endeavor to reach some one of the free States. All persons are herby cautioned against harboring said slave, and masters of vessels from carrying her from this port. The above reward will be paid on delivery to MARY D. SAYER, Granby street. $50 REWARD. Ran away on Monday night last, my negro man George, commonly called George Latimer. He is about 5 feet 3 or 4 inches high, about 22 years of age, his complexion a bright yellow, is of a compact, well made frame, and is rather silent and slow spoken. I suspect that he went North, Tuesday, and will give Fifty Dollars reward and pay all necessary expenses, if taken out of the State. Twenty Five Dollars reward will be given for his apprehension within the State. His wife is also missing, and I suspect that they went off together. JAMES B. GRAY.”

[16] Asa J. Davis, “The George Latimer Case,” The George Latimer Case; Story of the Hutchinsons (Tribe of Jesse) Volume 2, (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1896), 350-351, Archive.org.

[17] Boston Directory 1842, (Boston: Stimpson & Clapp: 1842), 439, Stimpson's Boston directory. [1842] : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

[18] Liberator, June 11, 1841, 2; Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, Ninth Annual Report of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, (Boston: Oliver Johnson, 1842), 2, Archive.org.

[19] “December Meeting, Gifts to the Society; The Office of Attorney General; The Crisis of the Civil War," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Volume 56, 1922, 170, December Meeting. Gifts to the Society; The Office of Attorney General; The Crisis of the Civil War : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

[20] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 18, 1842, 4.

[21] Liberator, October 28, 1842, 3; Liberator, November 4, 1842, 3; Liberator, December 23, 1842, 2.

[22] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 16, 1842

[23] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 23, 1842, 3.

[24] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 23, 1842, 3; Liberator, October 28, 1842.; Liberator, November 4, 1842, 3.

[25] The Liberator, November 18, 1842, 2.

[26] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 11, 1842, 1.

[27] Boston Post, November 18, 1842, 2.

[28] Latimer Journal and North Star, November 23, 1842, 3.

[29] Later in his life, Latimer attributed his freedom to Reverend Caldwell and donations from the Tremont Temple Baptist Society: “I recall with gratitude the generous act of Rev. Dr. Caldwell, of the Tremont Temple Baptist Society, who raised the money with which I was redeemed.” However, multiple sources from 1842 state Reverend Nathaniel Colver as the person who paid for George’s freedom. It is possible Caldwell was somehow responsible for some of the funds raised at Tremont Temple.

Latimer Journal and North Star, November 23, 1842, 3; Liberator, November 25, 1842, 3; Liberator, December 9, 1842, 1; Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889, (New York: Penguin Press, 2012), 73.

[30] Liberator, January 20, 1843, 3.

[31] Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions; Passed Acts; St. 1843, c.69, SC1/series 229, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, Mass, Harvard Mirador Viewer.

[32] Liberator, December 9, 1842, 2; Boston Post, December 31, 1842, 2; Liberator, January 27, 1843, 2.

[33] Boston Post, December 31, 1842, 2.

[34] Liberator, February 3, 1843, 3; Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions; Passed Acts; St. 1843, c.69, SC1/series 229, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, Mass, Harvard Mirador Viewer.

[35] James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians; Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, Revised Edition (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999), 108.

[36] 1843 Massachusetts Acts Chapter 69, Acts and resolves passed by the General Court.

[37] “Rebecca Latimer,” Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, U.S., Vital Records, 1640-1849 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2023, Massachusetts, U.S., Vital Records, 1640-1849 - Ancestry.com; “Latimer, George,” Massachusetts City Directories, Chelsea, 1848, 44, Ancestry.com - Massachusetts, U.S., City Directories; Glennette Tilley Turner, Lewis Howard Latimer, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991), 19, Archive.org.

[38] Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W. B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, 18, https://archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/mode/2up.

[39] Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, 32, 34, 52.

[40] Municipal Court for the City of Boston, Dockets, Commonwealth v. Latimer, Apr. 1854, docket no. 227. JU-SJC/DIS.SU.MCB/series 001. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts; Municipal Court for the City of Boston, Record books, Commonwealth v. Latimer, Apr. 1854, Pg. 464. JU-SJC/DIS.SU.MCB/series 002. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts; Municipal Court for the City of Boston, File papers, Commonwealth v. Latimer, Apr. 1854, docket no. 227. JU-SJC/DIS.SU.MCB/series 003. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts.

[41] Frederick Douglass' Paper, February 24, 1854, 3, https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84026366/1854-02-24/ed-1/.

[42] Municipal Court for the City of Boston, Dockets, Commonwealth v. Latimer, Jan. 1858, docket no. 98. JU-SJC/DIS.SU.MCB/series 001. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts; Municipal Court for the City of Boston, Record books, Commonwealth v. Latimer, Jan. 1858, Pg. 27 verso. JU-SJC/DIS.SU.MCB/series 002. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts; Municipal Court for the City of Boston, File papers, Commonwealth v. Latimer, Jan. 1858, docket no. 98. JU-SJC/DIS.SU.MCB/series 003. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Massachusetts.

[43] They are listed as paupers in the 1855 Massachusetts State census. Opened in 1854, the Tewksbury Almshouse was one of Massachusetts’ first state-run almshouses, an institution which provided services to the poor. “George Latimore,” Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, U.S., State Census, 1855 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014, Massachusetts, U.S., State Census, 1855 - Ancestry.com.

[44] “Margaret Latimer,” Ancestry.com, 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009, Images reproduced by FamilySearch, 1860 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com; “William Latimer,” Ancestry.com, 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009, Images reproduced by FamilySearch, 1860 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com; Glennette Tilley Turner, Lewis Howard Latimer, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991), 19-22, Archive.org.;

[45] Glennette Tilley Turner, Lewis Howard Latimer, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991), 22, Archive.org.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Glennette Tilley Turner, Lewis Howard Latimer, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991), 23, Archive.org.

[48] Boston City Directory, 1865, (Boston: George Adams, 1865), 121, The Boston directory. [1865] : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive; “Rebecca Latimer,” Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 - Ancestry.com; “Rebecca Freeman,” Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., State Census, 1865 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014, Massachusetts, U.S., State Census, 1865 - Ancestry.com;

[49] “George Latimer,” U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007, U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865 - Ancestry.com; “Latimer, George,” National Park Service, Soldier Details - The Civil War (U.S. National Park Service).

[50] At only 16 years old, Lewis served as a landsman on USS Massasoit. ; “Latimer, Lewis,” National Park Service, Search For Sailors - The Civil War (U.S. National Park Service); Brooklyn Eagle, August 16, 1910, 5.

[51] Glennette Tilley Turner, Lewis Howard Latimer, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Silver Burdett Press, 1991), 22-23, Archive.org.

[52] “George Latimer,” Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook), Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 - Ancestry.com.

[53] “Charles Latimer,” Year: 1880; Census Place: Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts; Roll: 559; Page: 405a; Enumeration District: 733,1880 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com.

[54] Rebecca Latimer,” Year: 1880; Census Place: Bridgeport, Fairfield, Connecticut; Roll: 95; Page: 708a; Enumeration District: 138, 1880 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com; “Oscar Freeman,” Year: 1880; Census Place: Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts; Roll: 554; Page: 405d; Enumeration District: 624, 1880 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com.

[55] National Park Service, “The Giften Men Who Worked for Edison,“ https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/kidsyouth/the-gifted-men-who-worked-for-edison.htm#:~:text=Lewis%20Howard%20Latimer%20(1848%2D1928) ; Edison Pioneers, Obituary of Lewis Harold Latimer, December 11, 1928. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b178-i618.

[56] “George Latimer,” Year: 1880; Census Place: Hartford, Hartford, Connecticut; Roll: 98; Page: 372c; Enumeration District: 017,1880 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com; “William H. Latimer,” Year: 1880; Census Place: Bridgeport, Fairfield, Connecticut; Roll: 95; Page: 708a; Enumeration District: 138, 1880 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com; “Margaret Hawley,” Year: 1880; Census Place: Bridgeport, Fairfield, Connecticut; Roll: 95; Page: 454d; Enumeration District: 128, 1880 United States Federal Census - Ancestry.com;

[57] “George W Latimer,” New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915, Massachusetts, U.S., Marriage Records, 1840-1915 - Ancestry.com.

[58] More than Freedom; Scott Gac, “Slave or Free? White or Black? The Representation of George Latimer,” The New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015): 93–94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718203.

[59] Scott Gac, “Slave or Free? White or Black? The Representation of George Latimer,” The New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015): 93–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24718203.

[60] Gac, 98.; Story of the Hutchinsons (Tribe of Jesse) Volume 2, (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1896), 350-351, Archive.org.

[61] Winifred Latimer Norman, Lewis Latimer, Scientist, (New York: Chelsea House, 1994), 77, Lewis Latimer : Norman, Winifred Latimer : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

[62] “George W Lattimer,” New England Historic Genealogical Society; Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1840–1911, Massachusetts, U.S., Death Records, 1841-1915 - Ancestry.com; Boston Globe, June 2, 1896, 12; Lynn Daily Item, June 1, 1896, 6.

[63] “Rebecca Latimer,” New York City Department of Records & Information Services; New York City, New York; New York City Death Certificates; Year: 1910, New York, New York, U.S., Index to Death Certificates, 1862-1948 - Ancestry.com; “Rebecca Latimer,” Connecticut State Library; Hartford, Connecticut; The Charles R. Hale Collection of Connecticut Cemetery Inscriptions, Connecticut, U.S., Hale Collection of Cemetery Inscriptions and Newspaper Notices, 1629-1934 - Ancestry.com.

[64] Brooklyn Eagle, August 16, 1910, 5.