Last updated: June 12, 2024

Article

Learn to Look at Petroglyphs and Pictographs

NPS photo.

Petroglyphs and pictographs are a window into life hundreds or thousands of years ago. The carvings and paintings connected people’s everyday lives with the natural and spiritual worlds. They featured anthropomorphic figures, animals, and design motifs. While the images may appear familiar, their meanings remain a mystery. Clues about their meaning come from their setting and archeological remains or ethnographic evidence, including stories and traditions passed through generations. When visiting petroglyphs and pictographs, please treat them with as much respect as you would any home or religious site.

Before you go, visit a park's visitor center or website to find out:

- What is known about the petroglyphs and pictographs?

- Who made them, and why?

- Are any areas damaged or off-limits?

- Are there any safety issues, like weather or challenging terrain?

- How can vandalism be reported?

Why are the markings here?

Observe your surroundings. Examine the topography, the path of the sun, the rocks and soil, and any animals or plants. See how shadow and light play across the rock surface. What do you observe? What significance does the setting have?

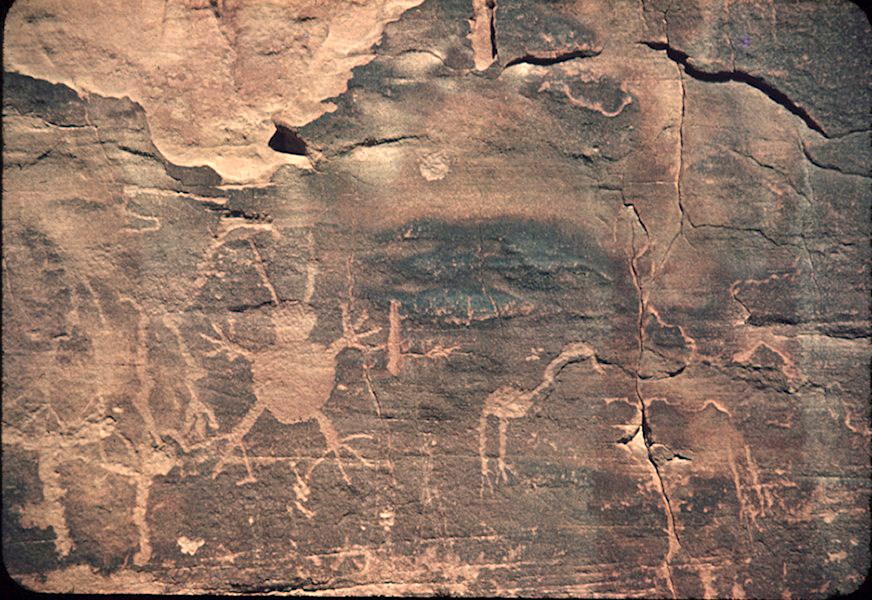

The context of petroglyphs and pictographs in time and space imbues them with meaning. Some accumulated one-at-a-time over a long period where people commonly gathered. Others were placed where they could track the sun, moon, and stars across the sky. Even more marked routes or destinations, such as transportation corridors or water sources.

NPS photo.

Petroglyphs at Puerto Pueblo in Petrified Forest National Park track the sun at the summer solstice. The sun falls through a crack in boulders to fall on the petroglyphs. For about two weeks around June 21, an interaction of light and shadow passes across the rings of this small, circular design as the sun rises.

NPS photo.

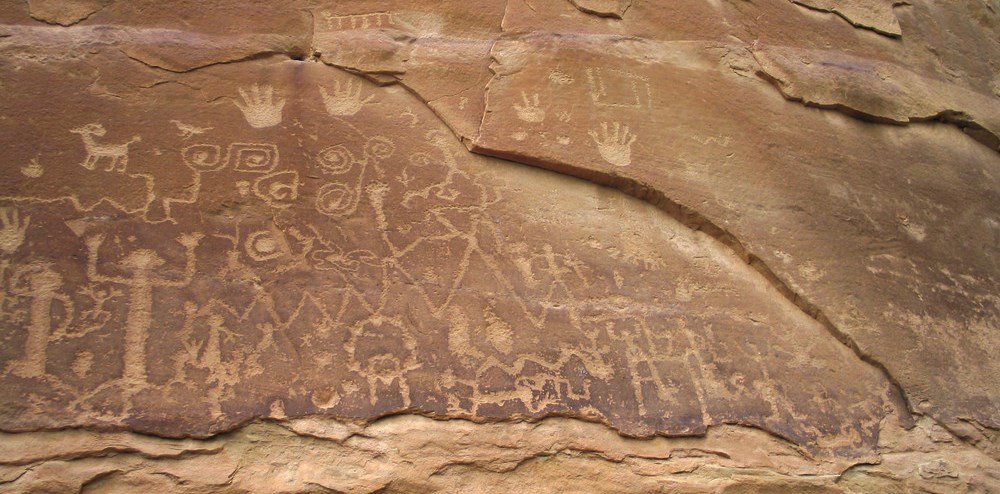

Nampaweep Canyon in Parashant National Monument was a passageway used by native peoples for migrating from the Grand Canyon to the higher elevation ponderosa pine forests located at Mt. Trumbull. Thousands of petroglyphs embedded into the smooth surface of basalt rock are thought to be records of events, memories, and stories of ancestors who had once passed through this canyon.

How did people get there?

Some areas where people left petroglyphs and pictographs are easy to access, but others took effort. People may have hiked, climbed, scaled a ladder or scaffolding, or paddled to reach the sites.How would people have reached the images you see? Are they accessible from the ground? Would you need a ladder or scaffold, or even a boat?

NPS photo.

Here is a person, for scale, next to anthropomorphic pictographs at Canyonlands National Park. Painters could walk right up to this rock face. See how the top of the figures is just within arm's reach? The painters may have stood on rocks at the bottom of the wall. While they worked, perhaps they hopped down and took in their progress from several steps back. The human scale and accessibility of the images may be intentional, and provide clues about how to interpret them.

NPS photo.

The Taíno carved petroglyphs at pools of water and in or near caves now within Virgin Islands National Park. The sites were easily accessible by foot. The Taino selected these spots to communicate through the petroglyphs to ancestors who assembled there. Taino petroglyphs included symbolic, anthropomorphic, and zoomorphic markings.

How were the images made?

Petroglyphs are carved, chipped, or ground into rock surfaces using handheld rock tools. One technique was to hold a rock and smash or grind it into the surface. Another technique was to hold one rock in one hand, and hit it with a hammerstone held in the other hand. Blunt rocks, pointed rocks, and edged rocks made different marks.Pictographs are painted onto rock surfaces using brushes, stencils, and other tools. Sometimes paint was even blown from the mouth onto the rock. The longest-lasting pigments were made from ground-up minerals mixed into a binding agent. People may also have created washes from plants, although these were less stable over time.

As you look at petroglyphs and pictographs, keep in mind that you are probably missing some of the picture!

NPS photo.

NPS photo.

NPS photo.

Is there depth, dimension, and movement?

In the scene above, which horses and riders appear to be closer to you? Which are further away? Are they positioned on top of each other like lines of writing on a page? Or can you imagine them spread into the distance? Do they appear to be moving across the scene?The makers of rock markings used tricks to create shape, depth, and perspective. Parts of a scene might be painted on rock forms or shapes to make the image jut out or recede. Markings might be larger or smaller relative to each other to create depth of field.

Some images may appear to move across the rock. Imagine: Lizards crawl to sun themselves on the rock. Horses and riders romp across the land. Bighorn sheep leap from crevice to crevice. A hunter stalking a deer hides behind a rock outcropping. A crowd of people wave their arms and dance, dance, dance.

See if changing your perspective adds to the effect. Get up closer, move further away, look from other angles. Squint. How does your view change if you imagine the images moving, instead of still?

What do the images remind you of?

Petroglyphs and pictographs have lines and shapes that may form recognizable motifs, such as anthropomorphic figures, animals, cosmological phenomena, and symbols. They may depict exactly what you think, or symbolize ideas or traditions. No one living today is sure what they are, or what they mean.Sometimes a figure of a deer is just a deer. But to the person who made it, the deer might mark a good hunting spot, represent a shaman or a ritual, or convey a feeling. The meaning is contextually significant in time and place to the people who made and viewed them.

NPS photo.

To do so, a visitor must know something about American signage. A diamond-shaped, yellow sign screwed to a pole along a roadway is a standard road safety warning. The visitor also needs to know what a buffalo looks like in silhouette. Together, the sign conveys that buffalo might be nearby and to watch out for them, because they might be in the road. The sign shows that shapes and colors can communicate something important, but only if you have enough pre-existing information to decode its symbols.

NPS photo.

Do you see vandalism?

Vandalism looks like modern painted or carved images over rock markings. As you can see from this image, visitors from the recent past have intruded upon rock markings from long ago. Common modern graffiti includes initials, names, dates, and even short phrases.Please do not make your own marks on petroglyph and pictograph sites. Vandalism makes it harder for visitors today to learn about and appreciate these fragile images from people who lived long ago, and it is illegal. Vandalism is also disrespectful of peoples who descended from the marks' makers. The markings are part of their ancestral culture and heritage.

What do you think?

Share what you've learned! Here are a few ideas:- Capture the scene in your own way: draw it, write a story, take a picture.

- Learn more about the people and culture who made the markings.

- Tell someone what you saw and what you think about it.

- Communicate with someone about your discovery.

- Write to a family member or friend. Explain / reflect on why you preserve the rock markings and how you might share this with others.