Part of a series of articles titled National Register and National Historic Landmarks Celebrate Jewish Heritage Month.

Article

Self-Expressionism: Lee Krasner's Jewish Heritage in Art

Library of Congress.

The artist Lee Krasner (1908-1984) created a strikingly diverse body of work, ranging in style from realism to cubism to abstract expressionism, and in form from paintings to collages to mosaics. The home Krasner once shared with her husband, fellow artist Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), was designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL) in 1994. NHLs are places that uniquely represent significant aspects of American history, and the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio memorializes this couple's remarkable artistic innovations.

Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Early Years

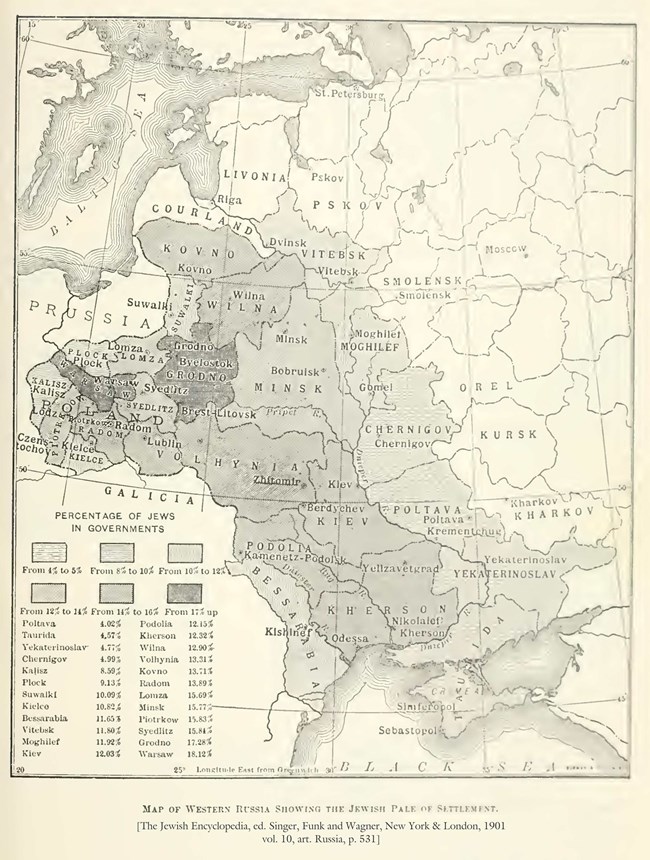

Lee Krasner was born Lena Krassner, on October 27, 1908, in Brooklyn, New York. Earlier that year, her parents, Chane and Joseph Krassner, had immigrated to the United States from the shtetl (village) then known as Spykov, and now known as Shpykiv, Ukraine. While the Krassners lived in Spykov, the town was part of the Russian Empire. The Russian Empire was hostile to Jews, confining them to a region termed the Pale of Settlement.The Krassners were one family among thousands of Eastern European Jews who immigrated to the United States during this era. Economic options in the Pale of Settlement were limited, and many Jewish families left out of financial necessity. Others fled antisemitic violence. Krasner (who later went by the name “Lenore,” and then “Lee”) was the first Krassner child to be born in the United States.

Krasner attended Hebrew school as a child. Since she was a girl, she wasn’t expected or allowed to attend an Orthodox cheder (school), which taught a more extensive Hebrew and theological curriculum to male students. Gender segregation in synagogues and patriarchal overtones in Orthodox Jewish practice provoked Krasner. She later commented that the daily prayer she learned to recite as a child was “beautiful… in every sense except for the closing of it… if you are a male you say, ‘Thank you, O Lord, for creating me in Your image’; and if you are a woman you say, “Thank you, O Lord, for creating me as You saw fit.”2

Chane and Joseph Krassner were devout Jews, but they didn’t insist that their children be equally orthodox. Krasner remembered that although she regularly attended synagogue services, her sister had decided not to, indicating that the Krassner children were given permission to decide how – or whether – they wanted to practice Judaism.

Krasner knew by age fourteen that she wanted to be an artist. By 1928, she became a student at the National Academy of Design. While there, Krasner learned how to paint what she saw in a directly representational way.

Artistic Vision

In 1937, Krasner began to study under the acclaimed German émigré art teacher Hans Hoffman. Krasner studied Cubism, perfecting the ability to convey forms as widely varied as human bodies, flowers, and buildings without depicting them directly.Krasner met fellow artist Jackson Pollock in 1941, after seeing his work at an art show in which they both were featured. They were tremendously inspired by each other’s art, beginning a romance that led to marriage in October 1945.

Photograph by CaptJayRuffins, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License, Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph by Rhododendrites, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License, Wikimedia Commons.

After Pollock’s death, Krasner embarked on a new phase of artistic expression. She moved her workspace from the second-floor bedroom to the barn where Pollock had painted. She spent long nights working, relying on electric lights to illuminate the studio. She used shades of black, white, and umber to create evocative abstract paintings that expressed her grief.6

Photograph by Americasroof, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 International License, Wikimedia Commons.

Legacy

Krasner’s nondoctrinaire Jewish identity and heritage shaped her art throughout her life. Krasner noticed that she always reflexively started her compositions in the upper right corner of her canvas, as she would begin to write a Hebrew text. Krasner’s long-lasting fascination with religious calligraphy – from lyrical Hebrew scrolls to illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells – permeated the colors and forms that appear regularly in her paintings.7Krasner’s legacy has been preserved and championed by curators and critics who are themselves Jewish women. Art historian Gail Levin listed Jewish women (herself included) who were enthusiastic advocates for Krasner’s legacy, including Barbara Rose, Hermine Freed, Marcia Tucker, Emily Wasserman, Cindy Nemser, and Ellen Landau.8

Krasner died on June 19, 1984. She was buried in Green River Cemetery, across from Pollock’s grave.

1 “Lee Krasner: In Her Own Words,” Barbican Centre on YouTube, May 10, 2019.

2 Gail Levin, “Beyond the Pale: Lee Krasner and Jewish Culture,” Woman’s Art Journal 28, no. 2 (2007): 29.

3 Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, Stony Brook University. See also Rachel Cooke, “Reframing Lee Krasner: the artist formerly known as Mrs Pollock,” The Guardian, May 12, 2019.

4 Ben Cosgrove, “Jackson Pollock: Early Photos of the Action Painter at Work,” LIFE, accessed February 16, 2024.

5 "Lee Krasner, 1978," DukeLibDigitalColl on YouTube, August 29, 2019. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel Video Archive, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

6 “Lee Krasner: The Umber Paintings, 1959-1962,” Kasmin Gallery, November 9, 2017-January 13, 2018; “Lee Krasner from the Depths of Despair to the Height of her Career,” Sotheby’s on YouTube, April 11, 2019.

7 Levin, “Beyond the Pale,” 29; "Lee Krasner, 1978."

8 Levin, “Beyond the Pale,” 32.

Last updated: March 19, 2025