Part of a series of articles titled Education Inequalities in World War II.

Article

Lesson 1: Education Inequalities in Japanese Incarceration Camps During WWII

Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority. June 4, 1942. National Archives. NAID: 538552.

The Munemitsu family had four children; Seiko, who went by Tad, Saylo, Akiko “Aki”, and Kazuko “Kazi.” The children were “Nisei,” second-generation Japanese Americans who were American citizens. In 1942 they attended their local schools in Westminster, California. After Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The Munemitsu children were forcibly relocated to Poston, Arizona.

This lesson is based on articles from Entangled Inequalities. Students will think about how Japanese Incarceration during World War II impacted children and education. It can be taught as part of a unit on World War II, Japanese Incarceration/Internment, or Civil Rights in the United States. It is the first in a series of three lessons about discrimination and education during World War II. You may teach it individually or as part of that series. You can find more lessons on Teaching with Historic Places.

Lesson Objectives:

Students will be able to…

-

Identify ways in which Japanese American students’ lives were disrupted and ways in which they tried to maintain normalcy.

-

Examine primary sources for perspective and context.

-

Evaluate whether Japanese American students were given equal opportunity for an education in the Incarceration Camps.

Essential Question:

How did World War II and Japanese Incarceration impact the education of Japanese Americans? Were their learning opportunities equal to students in the rest of the United States?

Warm Up: Picturing your Classroom

What are the things you think you need to have a successful time in school? Draw a picture of your own classroom and write a 1-2 sentence caption. What do you want to focus on? It can include materials and school supplies, people, or other parts of your environment. Are those things available in all school buildings or are they special to a particular classroom you have right now?

Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, January 4, 1943. National Archives. NAID: 536622.

Background Reading:

For more information, visit Entangled Inequalities: “Questions of Labor and Loyalty: Japanese Incarceration and the Munemitsu Family.”

In 1943, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order required all people of Japanese descent, including American citizens, living on the West Coast to be incarcerated at a series of camps. This included the Munemitsu family in Westminster, California. Families gathered the belongings they could carry and boarded government buses.

Some, like the Munemitsus, had neighbors they could trust to look after their land and property. The banker who helped the Munemitsus buy their farm, Frank Monroe, helped lease the land to a Mexican American family, the Mendezes, while they were away. Other families were not so lucky, and their homes and businesses were looted.

When people arrived at the camps, like Poston War Relocation Center where most of the Munemitsu family was sent, they found empty barracks. 18,000 people lived in three camps in Poston, Arizona on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. The schools weren’t finished. Part of the work in the first few months at Poston was to set up places to live and to set up the school. Everyone worked together to build the schools and other aspects of life.

School finally opened by October 1942 in Poston, enrolling 5,300 children from preschool to high school. Like in other camps, the buildings were overcrowded and there weren’t enough teachers. Average student-teacher ratios were 48:1 in the elementary schools. Some teachers were also of Japanese descent. Others were white teachers who lived in the camps. Some high school or college age students applied for passes to leave the incarceration camp and attend school elsewhere. US officials granted these passes as long as the students went east, away from the Pacific Coast. People also organized activities and clubs for both children and adults. Aki and Kazi attended third and fourth grade at the elementary school at Poston Camp 1.

In 1945, US officials released people at Poston and the other incarceration camps. When, and if, they returned to the West Coast, many had to start over. There was still anti-Japanese discrimination. The Munemitsus worked for and with the Mendez family, their tenants, as they adjusted to life back in California.

Vocabulary:

You can see the entire “Glossary of Terms related to Japanese American Confinement”

Issei: the first generation of immigrants from Japan, most of whom came to the U.S. between 1885 and 1924.

Nisei: second generation Japanese Americans, U.S. citizens by birth, born to Japanese immigrants (Issei).

Incarceration Camp: the sites where the US government forcibly relocated thousands of people of Japanese descent during World War II. Sometimes referred to as “internment camps,” those incarcerated, and their descendants prefer this term as more accurate because it does not make a judgement about a person’s wrongdoing

War Relocation Centers: the term used by the WRA to describe the facilities in which most Japanese Americans were held during World War II. The WRA administered ten such centers, most surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by military police. War relocation centers are also referred to as “incarceration camps,” “prison camps,” “internment camps,” and “concentration camps.”

Teacher’s Tip: Many of the resources below are from other Incarceration Camps, not just Poston. You may have students ask about the reliability of photographs or drawings from different camps. This is an opportunity to talk about the use of case studies or how historians make inferences based on the sources available, even if they are not the sources they would always like.

Activity 1: Picturing Incarceration

Using the following image and caption, have students discuss questions what school may have been like for Japanese American children in Incarceration Camps.

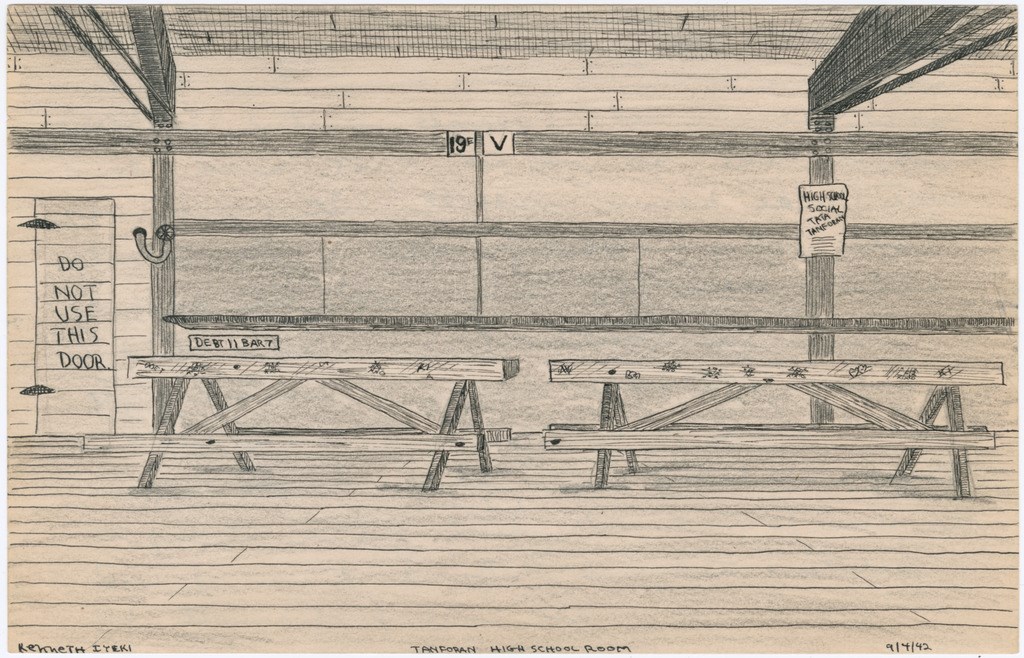

Kenneth Nobuji Iyeko. “Drawing of the inside of a classroom at Tanforan Assembly Center.” San Bruno, California: September 4, 1942. From the Kenneth Nobuji Iyeki Collection, courtesy of the Densho Digital Repository

Kenneth Iyeki wrote the following caption to the picture: “This is my wonderful history class (under the grandstand). The entire school was housed under one roof with no partition between classes. There would be so much noise that one day we, weather permitting, the teachers would [?] their classes out on the grandstand where there would be less noise. The wall partitions which appear as a blackboard one merely [?] which hide the openings which were [?] used as [?]. I can imagine all the money that passed from packet to packet in my history class. Sort of makes it hard for one to concentrate on what Aristotle did thousands of years ago.”

Picture Analysis Questions:

-

What do you see in the picture? What details tell you this is a classroom? What is unexpected or different about this classroom?

-

Based on the image and the caption, do you think that Japanese Americans were getting a fair education during World War II?

-

How does this picture compare to your drawing of your classroom? What does that tell you about similarities and differences between your school and schools in the Incarceration camps?

-

How does Kenneth’s, the artist, caption impact your understanding of what the classroom was like?

-

Who drew the picture? What do we know about the artist? How does that impact what he might have drawn?

Activity 2: Through the Government Lens

Look closely at the following photographs, then answer the questions below. These photographs were all taken by photographers working for the War Relocation Board, the federal government agency in charge of overseeing the evacuation of people of Japanese descent from their homes and running the Incarceration camps. The photographs were made to document “the daily life and treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II” (National Archives.)

*Teacher Tip: Students can look at the pictures and make observations before learning about who took them and why. This is an opportunity to talk with students about perspective. Push students to think about why the pictures below are different than the pencil drawing from the previous activity. Remind them it is not just the medium (photographs v. drawing) but the people who made them and why they were created that makes the sources different.

Picture Analysis Questions:

-

What do you see in the photos? What can you infer about what school was like in Japanese Incarceration Camps?

-

How do the photos compare to Kenneth Iyeko’s drawing of the classroom? What is similar and different? Why do you think that is?

-

How might the perspective and purpose of these photographs impact what is being depicted?

-

How does the different perspective from Kenneth’s drawing impact how you interpret each image?

-

What can you corroborate about education in the camps from multiple sources? What do you still want to know?

Activity 3: Letters from Incarceration Camps

Teacher Tip: The following are excerpts from letters specifically about education. You may want to direct students to the Japanese American National Museum’s Clara Breed Collection and let them explore the letters more freely to learn about daily life for children in Poston and other Japanese Incarceration Camps.

Teacher Tip: This activity can be completed as a jigsaw. Have students focus on one of the primary sources. Then have them discuss their analysis with students who read different documents.

Clara Breed was a librarian from San Diego, California. When many members of her community were relocated to incarceration camps hundreds of miles away, she encouraged the young people to keep in touch, sending them books and self-addressed envelopes with stamps. She received over 250 letters and postcards from Japanese American children during World War II. Letters to her give us a glimpse on what life was like for students at the time. Pick one of the letters and answer the questions below:

Letters to Miss Breed

Postcard to Clara Breed from Jack Watanabe. Poston, Arizona, October 6 1942.

10-6-42

Dear Miss Breed,

This is just a line to let you know that we received the books that you recently sent. I want to thank you for all those wonderful books that you sent. I can't tell you in words how much we all appreciated them. /We are now in a strange place--Poston, Arizona. I doubt whether this is even on the map. It's near Parker (a small town) This is located in the South-western part of Arizona. There are many Caucasian school teachers here. School started yesterday for grammar, junior, + high school grades. There is no restriction--hardly--on visitors. Just so you let these people know a few days in advance and get a "pass". Just thought I'd let you know--/We're right in the midst of a thunderstorm. The rain is coming down in "sheets". Lightning is awful. This is the worst storm I've ever been in. Will write more about this place later. Thanks again for the books.

Bye /Jack Watanabe

Courtesy of the Japanese American National Museum

Letter to Clara Breed from Louise Ogawa. Poston, Arizona, November 11, 1942.

November 11, 1942

Dear Miss Breed,

Since the last time I wrote nothing exciting has occurred. We are all in the finest of health. I hope you will receive this letter in the best of health./ Saturday, Nov. 7th I experienced something which I shall never forget. I went cotton picking with my fellow school-mates to raise funds so the school will be able to have a school paper./We left home at 8:30 A.M. on a cattle truck. We were going bumpity bump down the narrow dirt road when all of a sudden we came to a halt. We quickly jumped to our feet and saw a little house with a military police sitting in it. Then we were counted like cattles and again were on our way. We went winding through the Mosquite trees until finally we were surrounded by cotton plants. Everyone cried out, "Well, here we are--let's get busy!" After piling out of the truck like ants, we were given a large sack in which to put the cotton. This sack was very very long... It weighed 2 lbs and often got in our way. We flung the bag over our left shoulder and began picking the cotton. I often crawled on the ground to pick the fallen cotton. It certainly was a good thing that I wore slacks and a long sleeve blouse because, you get scratched all over…. Even though I had no water and came home exhausted I enjoyed every minute of it. It certainly felt good to get home!!

Courtesy of the Japanese American Nationanl Museum.

Letter to Eleanor Breed from Yukio Tsumagari, Santa Anita Assembly Center Arcadia, California, August 7, 1942.

Dear Miss Breed,

…Camp life here in Santa Anita is very complete in the sense of organization. The camp has been divided into various districts from one to seven in order to facilitate the housing and feeding of all the evacuees. Each district has a mess hall which is identified by a shade of color. Each mess hall has a seating capacity of approximately fifteen hundred. Post offices, toilet facilities are distributed through the camp. There is one main Hospital in camp equipped with surgical & medication to care for the sick. / For the sake of maintenance of mental pacificity there are several very well organized departments. The recreational, education departments are the two largest and most active departments in camp. The primary purpose of both departments is to keep both adult + children occupied mentally or physically in some fashion. The recreational department have numerous baseball, softball, wrestling, weight lifting leagues + contests; clubs of all sort including boy + girl scoutings, sewing, knitting classes and even dancing + art classes. In the education department, with what facilities they have, there is organized school for adult and children from the first to the seventh grade. The school is on a pure voluntary basis, that is on the part of the students. There is a library made of books accumulated by various clubs. Books have been donated by various libraries and individuals from the outside. / Although the camp may seem complete in various ways, there are many disadvantages as you can readily see. Discontent with present conditions has been the root for many disorders lately ….”

Analysis Questions:

-

Who is writing? What do you know about the author of the letter?

-

Who are they writing to? [What is different about the reader and the author?]

-

What do you learn about school in the incarceration camp?

-

What about the intended reader might impact what is written? Do you think this is the complete story of what is happening at school?

-

Talk to students who read different letters. How do the letters corroborate what you learned about the schools from the images? What new information do they tell you?

Exit Activity:

Teacher Tip: You can collect this exit ticket in whichever way best suits your classroom. This may be a chance for students to share with each other, by posting to your classroom online forum or sticky notes on the wall to facilitate conversation next class. You can also have them submit, on an index card or a private online assignment, for you to check for understanding.

How would you characterize Japanese Americans’ school experience during World War II? How do you feel this experience fits with messages and promises of the United States generally and during the War specifically?

Additional Resources:

In addition to exploring the Entangled Inequalities site, you should check out the following resources.

Look through Kenneth Iyeki’s other drawings from his life during and after World War II in the Densho Digital Repository collection.

Read other letters from students to Clara Breed talking about their time in the Japanese incarceration camps.

Explore exhibits and primary sources, including “Don’t Fence Me In: Coming of Age in America’s Concentration Camps” at the Japanese American National Museum

This lesson was written by Alison Russell, an educator and consulting historian for the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

Tags

- entangled inequalities

- japanese american incarceration

- japanese american internment

- japanese american history

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- ww2

- education history

- education

- california

- arizona

- poston

- relocation camps

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- aapi

- asian american and pacific islander history

- twhp

- twhplp

- teaching with historic places

- education inequalities

- japanese american

- japanese americans

Last updated: April 3, 2024