Last updated: March 21, 2023

Article

Measuring Up

Only a handful of US Park Police (USPP) officers from the 1940s through 1970 were women. In 1972, however, two events opened the door to change. Thirty years after the first policewomen were hired, women officers were uniformed, making them publicly visible for the first time. In addition, a legal challenge to USPP’s minimum height and weight standards for women brought at least the promise of more opportunities for policewomen.

Women at a Crossroads

USPP's early progress hiring policewomen in the 1940s stalled during the 1950s and 1960s. No new women officers were hired and by the late 1960s, the policewomen hired in the 1940s had retired or were working in administrative positions.

By 1970, women were more likely to find USPP jobs as "seasonal employees for parking control and public assistance" (sometimes referred to as meter maids or crossing guards) than as police officers. The public safety positions were temporary and the names of the women hired are not readily available. Although a 1971 photo documents a dozen women working that summer (most of whom were women of color), it's not known how many women were hired in any given year. By 1976, the jobs had been retitled "park aides."

Although they were not policewomen, they were the first women in USPP to be uniformed. Their uniforms consisted of black skirts with blue stripes down the sides, white short-sleeved blouses, white gloves, and blue hats modeled after the US Navy’s World War II WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Service). Although the hat included the USPP insignia on the front, the women did not wear badges or aparently patches on their shirts.

Policing Half the Population

As the 1970s dawned, more women looked to become police officers with USPP rather than parking enforcement officers. In June 1970, Shirley Long passed the examination to become a USPP officer but she wasn't offered a job. Among the reasons cited was that she did not meet the minimum requirements of 5'8" and 145 pounds. However, those standards were not put in place until after she applied.

Sometime during summer 1971, the Americans Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a discrimination claim on Long's behalf. The ACLU argued that the standards made 98 percent of American women ineligible. The National Organization for Women (NOW) also took up Long's cause. In January 1972 a group of NOW women demonstrated outside the Department of the Interior. They distributed leaflets titled, “We Can No Longer Permit One Half of the Population to Police the Other Half” and which demanded that “50 per cent of Park Police in all phases of police work be women.”

In November 1972 the Civil Service Commission’s Board of Appeals and Review ruled that the practice was sex discrimination, noting that there was “no rational relationship” between the minimum standards and USPP work, most of which involved traffic duty at the time. The board also ruled that Long be hired to fill the next available USPP vacancy. Despite her legal victory, it appears that she never worked for the USPP.

Training with the Men

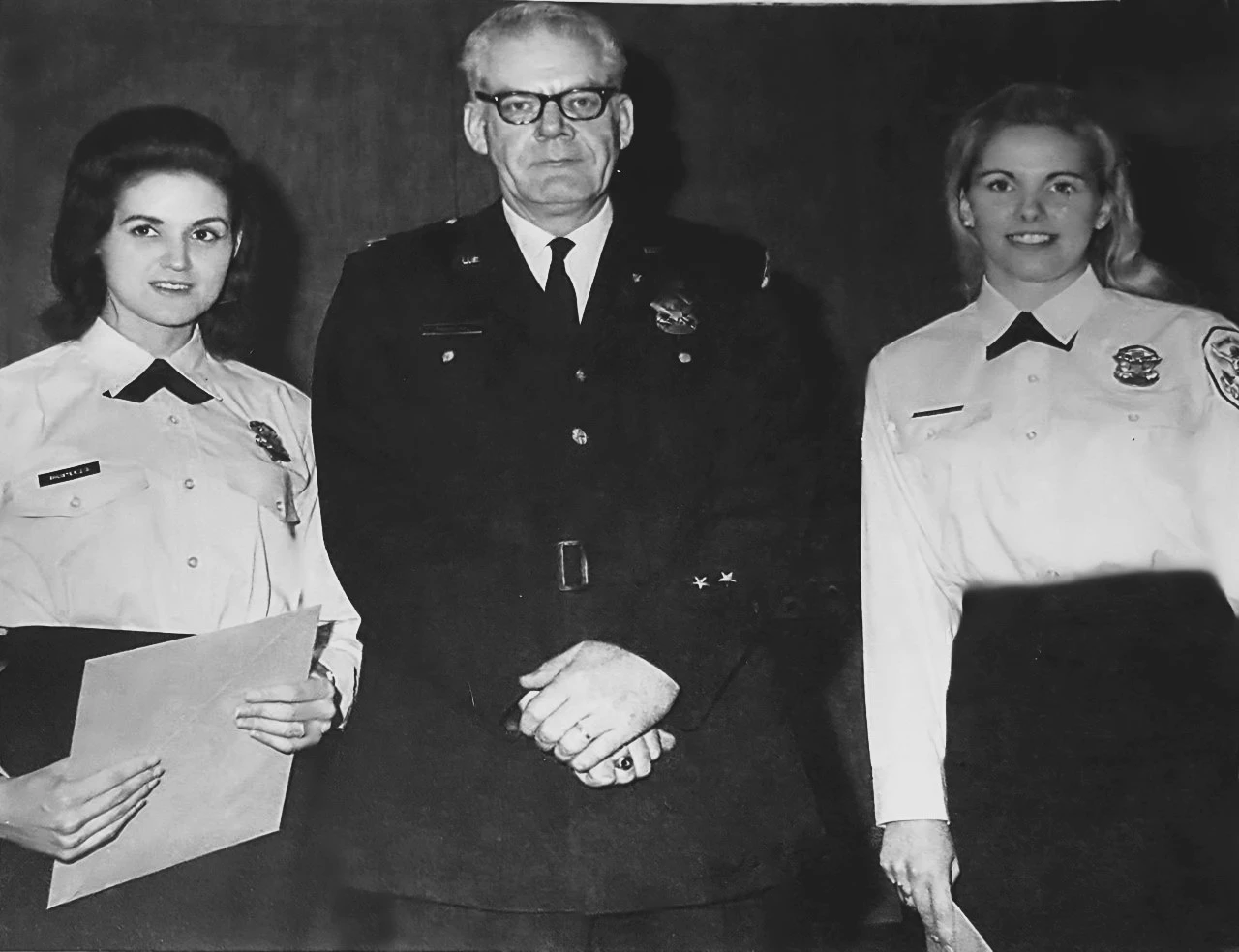

The USPP policewomen working from the 1940s through the 1960s were all plainclothes officers. That changed when Judy Shuster and Paulette Dabbs became the USPP’s first uniformed policewomen in 1972.

Dabbs and Shuster both joined USPP on December 26, 1971. They had to meet the minimum height (5’8”) and weight (145 pounds) standards for USPP officers. Judy Shuster (now Ferraro) recalled trying to gain weight to qualify but that at weigh in she was still too light by a pound. She remarked, “If you had weighed me right after breakfast, I would have been 145 pounds.” They let her in.

They were part of class 1971a (December 1971 to April 1972) at the Consolidated Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (CFLETC) in Washington, DC. The US Secret Service conducted the firearms training. Swimming was also done offsite. The third woman in the class was Donna Simms who was training as a park ranger. Judy Shuster Ferraro recalled,

They were very adamant that we had the same exact training as the men. If they ran a certain amount, we had to run the same. If they did a certain amount of sit ups, we had to do the exact same. They were very strict with that.

Looking the Part

Although USPP was “so anxious at that point to push a woman up” as Ferraro recalled, it was unprepared for the realities of women officers. One area where this was apparent was the lack of a woman’s uniform. In the photo above, Simms is wearing the NPS 1970 women’s uniform, but Dabbs and Shuster are wearing civilian clothes. The eight USPP men are all in uniform.

Ferraro recalled that the uniform was created right before she and Dabbs graduated. “I think they had crossing guards at the time that wore skirts. Well, they took those skirts and put a blue stripe down them. And then we went over to 8th and Eye Streets to the Marine Corps’ dress shop across the street from the barracks, and they put a uniform together. We wore the men's shirts. It didn't fit too well. We were supposed to have the necktie like the men, but unfortunately, on the day of graduation, I lost my tie. And so, they went downstairs to the Executive Protective Service and got those little cross Tuxedo ties, I think they called them, so that was our uniform."

The basic uniform looks remarkably similar to that of the temporary "meter maids" documented in the photograph above, right down to the hat and, on ocassion, the white gloves. Ferraro recalled the hat noting, “It looked like an inverted tea strainer or something. It was awful. And we had a straw one in the summer, and sort of a felt one in the winter, but they were pretty outrageous.”

Of course, there were some key differences between the uniforms such as the tie, the uniform shirt with USPP shoulder patch, and, as Ferraro noted, “Come winter, we got pants and a winter coat.” Most notably, however, both Dabbs and Shuster wore badges and carried sidearms. Like the men, they wore the Sam Brown belt across their chests and around their waists to hold their pistols. At first they were issued detective special pistols but later were given 4-inch .38 pistols.

Initially, the uniform included pumps which were uncomfortable and impractical. “We found that out real fast, and they took us down and bought us another pair of shoes that looked like a nun's shoes. We just had to agree, both of us, what we would wear, and so we picked something that was comfortable to walk in, because those first ones did not cut it for a foot beat.”

A women’s uniform shirt was created in 1973, providing a better fitting option. By ca. 1974, the skirt was replaced by trousers year-round, but the crosstie and the hat remained until around 1978. Beginning in 1979, woman and men wore identical uniforms.

Although Shuster and Dabbs weren’t the first USPP policewomen, their uniforms made them the first who were publicly visible. Ferraro remarked, “If I had a dollar for every time my picture was taken in front of one of these memorials, I'd be wealthy because it was such a novelty. Nobody was used to seeing a woman with a gun in uniform.”

Demonstrations and The Ballgown Beat

Like other new recruits, Shuster and Dabbs worked foot patrol their first year. After a short training period, they patrolled without partners. They rotated through the same shifts as the men which meant doing solo patrols at night. They didn’t usually work together except for special assignments, including demonstrations where women might need to be searched.

Ferraro recalled that their first demonstration was a protest against the Vietnam War. She remembered, “They were putting these people they were arresting on buses, and we had to search the females before they put them on the bus.” Some demonstrators mocked their uniforms, saying that they looked like stewardesses. Shuster always responded, "Yeah, ride the friendly buses of the United States Park Police."

Working during demonstrations often involved a lot of waiting. Ferraro recalled, “They would have all the police on the bus and just a handful [on the streets]. If anything started, everybody on the bus would have to go out. There were like three or four buses of police. You'd be sitting on a bus for eight hours sometimes. I'd read a book. Paulette [Dabbs] would have sewed or knitted or something. That's the only time we were really together."

At the time, USPP was the only federal agency in Washington, DC with women police officers. As a result, Shuster and Dabbs where sometimes loaned out when another agency needed women officers. Ferraro recalled working the inaugural events for President’s Richard Nixon’s second term in January 1973. The Secret Service purchased the gowns she and Dabbs wore as they mingled at the inaugural ball, alert for security threats. Later USPP policewomen also attended the balls undercover. Shuster was also featured in a US Department of Treasury training film.

A Delayed Benefit

The 1972 determination in Long's case that the minimum height and weight standards were discriminationatory was significant but it didn't change USPP overnight. It was a couple of years before women applicants started to benefit from the ruling. In the meantime, women like Janice A. Rzepecki and Jane P. Marshall, who met the minimum standards, were hired. In practice, it seems that the height restriction was eliminated first, but even that step began Tipping the Scales towards more women on the force.

Sources:

“Discrimination Decision.” (1972, November 30). The San Bernardino County Sun, p. A-10.

Ferraro, Judith. (2022, July 12). Pers. Comm. with Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Ferraro, Judith. (2022, July 22). NPS Oral History Collection, NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.

Mackintosh, B. (n.d.). National Park Service: History of U.S. Park Police. National Park Service. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/police/police6.htm

"NOW Protests Sexism in the Park Police." (1972, January 21).The Washington Daily News.

Paulette Tubbs. (n.d.). Linkedin. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://www.linkedin.com/in/paulette-tubbs-42bb2a78/, retrieved May 26, 2022.

Retired US Park Police Association. (2016). United States Park Police 225th Anniversary. Acclaim Press, Moreley, Missouri.

US Park Police. (1971). Annual Report for the Year 1971. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.