Last updated: February 9, 2024

Article

Osage Orange at the Worthington Farm, Monocacy National Battlefield

NPS

Specimen Details

- Location: Worthington Farm, Monocacy National Battlefield, Frederick, Maryland

- Species: Osage orange (Maclura pomifera)

- Landscape Use: Hedgerow, living fence

- Age: Estimated planting between 1850-1890

- Condition: Fair to Good

- Measurements: N/A (recently pruned to root flare, see Preservation Maintenance section below)

NPS

Significance

Griffin Taylor built the house now known as the “Worthington House” around 1851, situated on 300-acres of agricultural land originally known as Clifton Farm. John F. Wheatley and T. Alfred Ball purchased this and the neighboring Thomas Farm following Taylor’s death in 1855. Ball occupied the house following the sale along with eight enslaved individuals who also lived on the property, ranging in age between 13 and 30 (1860 Frederick County Slave Schedule).

John T. Worthington purchased the farm in 1862, which he renamed Riverside Farm. The Worthington family were living on the farm during the Civil War’s Battle of Monocacy. On July 9, 1864, Confederate troops crossed the Monocacy River to Worthington’s farm and advanced on the Union lines from its fields. Following the battle, the farm was used as a field hospital.

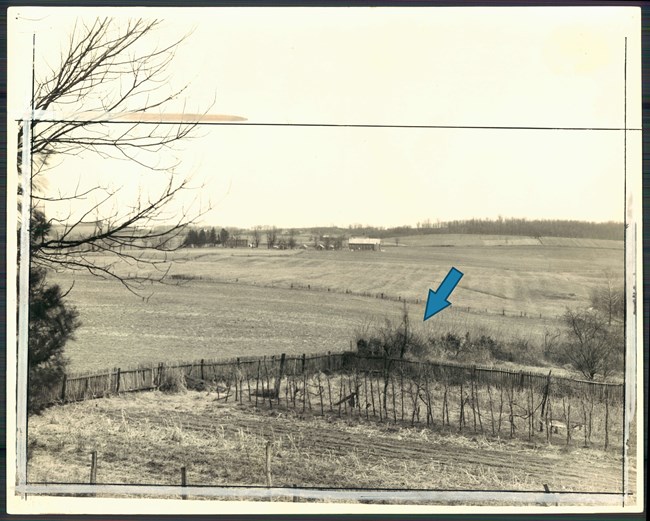

Although its exact date of construction is unknown, Worthington presumably planted the Osage orange hedgerow that grows south of the Worthington House as a living fence to demarcate boundaries around the kitchen garden and orchard. There were also Osage orange hedgerows lining a sunken road north of the house. Worthington produced winter wheat, Indian corn, hay, and butter on the farm and maintained a variety of livestock including cows, horses, swine, and oxen. The rectangular stand of Osage orange trees would have protected the kitchen garden and orchard from grazing livestock.

NPS

Baltimore Sun Historic Photos/TCA

Galen Hahn, a migrant minister during the 1960s recalled the poor living conditions of the migrant workers at the Worthington Farm, stating that they lived in the “old farmhouse with a row of barrack-type rooms, and a converted cow barn.” As Hahn described, there was no running water at the encampment and “[the workers] do not seem to be considered even human beings in the agricultural business; they are tools to be used for profit rather than simply human beings looking for a job.” The relatively recent use of the site to house migrant workers highlights the continuation of exploitive agricultural labor practices that predates the Civil War at the Worthington Farm. Ongoing research by NPS staff promises to yield additional information about the lives of migrant workers at Worthington Farm during the mid-twentieth century.

NPS

Botanical Details

First brought to the east coast from its native mid-western habitat in 1803, commercial growers began selling Osage orange in the region by the mid-19th century due to its use as hedging. Property owners planted living fences for their visual appeal and effectiveness for corralling livestock and as a windbreak.While the Osage orange hedge south of the Worthington House was pruned to four feet in height during the 19th century, Osage oranges can grow to up to 40 feet. Osage orange was available commercially in Maryland by 1848, but lost favor near the end of the 19th century as it hosted the San Jose scale insect, which damaged orchard produce such as apples and pears.

Preservation Maintenance

This Osage orange hedgerow was pruned during a landscape rehabilitation project at the Worthington Farm in late 2020. The project removed a non-historic stand of trees to reestablish views between the Worthington and Thomas Farms that were critical during the Battle of Monocacy. The Osage orange had grown to their maximum height of approximately 40 feet with a canopy spread of about 20 feet, obscuring the view between the two farms.

NPS

Learn More

Viewshed Restoration

NPS

NPS coppiced the hedgerow to just above the root flare (the base of the tree at the point of transition between the trunk and the root system) and the park will allow its shoots to grow annually to between four and six feet to approximate the historic height of the hedgerow.

Coppicing is a woodland management technique that relies on the ability of many tree species to propagate through the growth of new shoots from the stump or roots. During coppicing, a tree is intentionally cut down to a specified height and allowed to regenerate through the shoots it sends up in response. This technique is used to harvest timber but can also be used to manage the size of woody plants, as in this case.

NPS National Capital Region Cultural Landscapes Program

Resources

- Commisso, Michael. Worthington Farm (Clifton): Cultural Landscape Inventory, Monocacy National Battlefield, National Park Service. Cultural Landscapes Inventory reports, 600204. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2013.

- Commisso, Michael and Martha Temkin. Cultural Landscape Report Thomas and Worthington Farms, Monocacy National Battlefield, Frederick County, Maryland. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2013.

Other Works Cited

- Hahn, Galen. Finding My Field. New York: Page Publishing, 2018.

- Pepper, Charlie. Trip Report: Monocacy National Battlefield Cultural Landscape Assessment/Osage Orange Treatment Alternatives. Unpublished, January 20, 2021.