Last updated: August 2, 2022

Article

Mosby's Rangers in the Shenandoah Valley

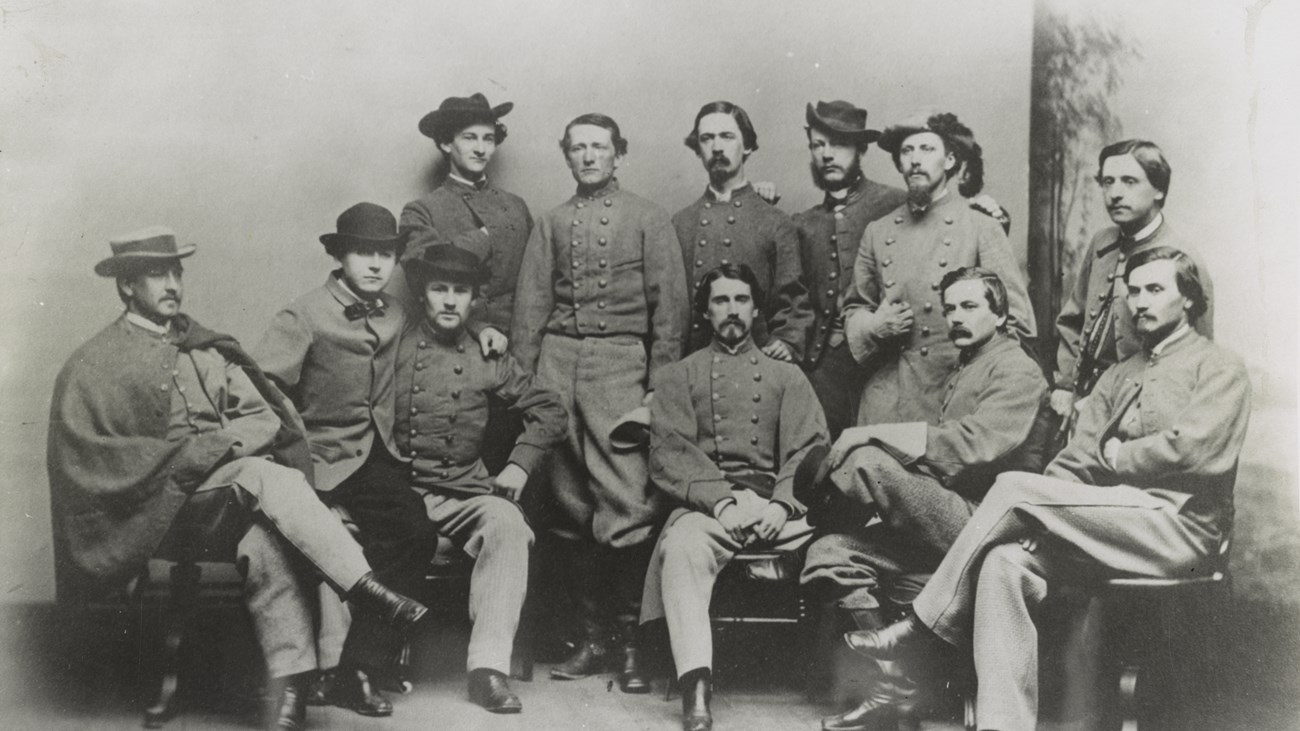

Library of Congress

“Only three men in the Confederate army knew what I was doing or intended to do; they were Lee and Stuart and myself…”

Col. John Singleton Mosby

Known as the “Gray Ghost,” Confederate Colonel John S. Mosby, along with his partisan rangers, terrorized Federal units in northern Virginia from late 1862 until the end of the Civil War in 1865. By the summer of 1864, Mosby and his men were disrupting the advance of the United States Army of the Shenandoah into Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

Mosby the Scout

Not a particularly enthusiastic soldier when he enlisted as a private in 1861, John Singleton Mosby disliked routine army life. After seeing limited action at First Manassas, however, Mosby was promoted to first lieutenant in the 1st Virginia Cavalry regiment. Enjoying the cavalry, but bored with his job as regimental adjutant, Mosby resigned and became attached to the staff of Brig. Gen. J.E.B. (Jeb) Stuart, then the cavalry commander of the Confederate army that soon became the Army of Northern Virginia. Mosby later wrote that Stuart, “made me all that I was in the war…the best friend I ever had.”

Mosby proved his worth as a scout and intelligence collector during the Peninsula campaign in June 1862. Riding with Stuart and about 1,200 Confederate horsemen, Mosby scouted ahead and along the column’s flanks in the infamous four-day circuit around the entire United States Army of the Potomac. He later scouted for Stuart during the Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg campaigns.

Proposing the idea of leading a band of riders to conduct guerrilla warfare in northern Virginia, Mosby convinced Stuart and Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee to authorize a company of rangers in January 1863. As the unit grew and gained notoriety, it eventually became Company A, 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, or Mosby’s Rangers, in June 1863. Although guerrillas, or partisan rangers, Mosby’s men were subject to the Articles of War and Army Regulations within General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

After over a year of successful raids to harass the enemy, gather intelligence, and strike Federal supply lines east of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, a new Federal threat appeared west of the Blue Ridge in the “breadbasket of the Confederacy,” the Shenandoah Valley. On August 7th, 1864, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan took command of the United States Army of the Shenandoah. With orders from Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to conduct “total war” to wipe out Confederate resistance in the Valley and burn crops and farms, Sheridan launched an offensive on August 9th. With a force of nearly 40,000 troops and a wagon train about twelve miles long, Sheridan’s army was both imposing and vulnerable.

Standing in Sheridan’s avenue to conquest was the tough, 14,000-man Confederate Army of the Valley under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early. Mosby twice offered his services to Early with little response. Ignoring Early’s indifference, Mosby decided to stretch his resources to defend the Valley anyway, “to vex and embarrass Sheridan and…to prevent his advance into the interior of the state.” Mosby was acting on his own; his best friend and mentor, Jeb Stuart, had been killed in action on May 12th, 1864.

Mosby got his first chance to attack Sheridan early on August 13th, 1864. With intelligence from his scouts, Mosby gathered about 300 rangers and rode into the Shenandoah Valley to ambush Sheridan’s column.

At sunrise, Mosby’s force struck just north of Berryville, Virginia. Although most of the Federals had passed, the wagon train of the Union Cavalry Corps was vulnerable. The rangers fired two cannon rounds, then charged into the unsuspecting Federal troops. Those who were not captured or killed, scattered. The rangers seized over 200 Federal soldiers, 500 horses and mules, 200 cattle, and about 100 wagons. After the wagons were plundered, Mosby ordered them burned.

Furious about what became known as the Berryville Wagon Train Raid, Sheridan dedicated an entire brigade to wagon train security, arming the soldiers with seven-shot Spencer repeating carbines. Sheridan also acquired the scouting and counterguerrilla services of the 100-man “Blazer’s Scouts” under the command of Captain Richard Blazer.

The conflict between Mosby’s Rangers and Sheridan’s troops in the Valley became increasingly brutal. In retaliation for the wagon train raid, Sheridan’s cavalry burned barns, crops, and mills.

Federal Brig. Gen. George A. Custer ordered the burning of five Berryville-area properties including the home of Benjamin Morgan. As troopers of Custer’s 5th Michigan Cavalry regiment began to torch the house on August 19th, three companies of Mosby’s Rangers under Captain William Chapman attacked, “Wipe them from the face of the earth! No quarter! Take no prisoners!” Chapman yelled. Estimates vary, but at least twenty Federals were killed and ten captured. The prisoners were allegedly executed, two with throats cut. One survivor lived to tell the gory tale.

Sheridan’s advance into the Valley stalled. The Army of the Shenandoah returned to the Harper’s Ferry area, with Mosby’s Rangers harassing it along the way. By early September, Sheridan launched a new offensive, this time with improved security.

Mosby, however, had plans to intercept and strike the Federal advance. Leading two companies of rangers himself, Mosby sent two more companies under Captain Samuel Chapman into the Valley on September 2nd.

Early the next morning, hearing reports of Federal troops near Berryville, Chapman approached the town from the southwest and met the 6th New York Cavalry regiment, a lead element of Sheridan’s force. Facing off in a farm field owned by the Gold family about one-half mile south of Berryville, Chapman split his companies into two attack wings and charged, yelling and screaming. Although armed with Spencer repeating carbines, the New Yorkers were killed, captured, or scattered. Federal casualties were reportedly 42 while the Confederates lost five.

After less than a month, Mosby’s combat tactics in the Valley were established. Always attack and use “terror” to gain an advantage, “always act on the offensive,” said Mosby. “At the order to charge, my men dashed forward with a yell that startled and stunned the enemy…it was safer…being the aggressor and striking the enemy at unguarded points.” If necessary, Mosby’s men were to escape into the nearby Blue Ridge Mountains.

Perfect for this fighting style were Mosby’s Rangers, most of whom were young, between 17-25, who sought the glory of war on horseback. Ranger John Munson wrote, “usually a young fellow who joined Mosby’s command came with romantic ideas of the partisan ranger’s existence.” Adding to the lure of ranger life, Mosby allowed his troopers to keep plunder from raids, “if men got rewards…of horses and arms, they were more devoted to the cause.”

A few rangers carried other weapons, but Mosby favored pistols, especially 1860 Colt Army revolvers, because they provided close-combat firepower without being cumbersome. “I had no faith in the saber as a weapon. We did more than any other body of men to give the Colt pistol its great reputation,” wrote Mosby.

Despite the appeal of riding with Mosby, it was dangerous to be a ranger. After Federal victories at Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, rangers again entered the Valley seeking ways to disrupt Sheridan’s lines of communication.

In a fight near Front Royal, Virginia, on September 22nd, rangers under Captain Sam Chapman mistakenly attacked a larger force of Federal cavalry escorting an ambulance convoy. In the ensuing firefight the Federals captured six rangers, but a Union officer was supposedly shot while down and trying to surrender.

The furious Federals wanted to take revenge against the six captured rangers; permission was granted, probably by Federal cavalry corps commander, Maj. Gen. Alfred Torbert. All six victims were either shot or hanged and three were buried in Front Royal’s Prospect Hill Cemetery. A seventh captured ranger was executed later.

Small, harassing raids continued in the Valley until October 14th when Mosby and approximately eighty rangers conducted the “Greenback Raid” near Duffield’s Station, about seven miles west of Harper’s Ferry. Wanting to create an impact event, Mosby and his men removed a rail and waited for the next westbound train to derail. When it did, rangers entered the cars, killed a Federal officer, and confiscated personal valuables from the passengers.

After the passengers were removed, rangers burned the train. Inside the train’s paymaster’s box was cash worth $173,000, which Mosby later divided between his ranger participants, about $2,100 apiece. The young rangers certainly enjoyed these “spoils of war,” but calls for recrimination and Mosby’s head grew louder in the North.

Brutality between the rangers and Federals was about to end, but not quite. At least partially in retaliation for the recent ranger executions in Front Royal, Mosby, through a lottery process, identified seven Federal prisoners to be hanged. Because he somehow blamed George Custer for the Front Royal affair, Mosby wanted most of the condemned Federals to have served under Custer.

On November 7th, 1864, in Beemer’s Woods just west of Berryville, rangers hanged three of the Federals, shot two, while the other two escaped in the night. The two soldiers who were shot survived to tell the gory tale. Mosby decided the mutual executions, being “repulsive to humanity,” should end and wrote Sheridan on November 11th, “Hereafter any prisoners falling into my hands will be treated with the kindness due to their condition…” Sheridan agreed and the brutality ended.

By November 1864, Mosby and his rangers were largely on their own in the Shenandoah Valley war. Sheridan had burned out most of the farms and crops. Jubal Early and his Confederate Army of the Valley had been soundly beaten at Cedar Creek on 19 October; no more reinforcements from General Robert E. Lee were coming.

But Mosby fought on. A constant irritant for Mosby over the past three months had been Blazer’s Scouts, the 100-man counterguerrilla force acquired by Sheridan in August.

After losing a sharp skirmish to the Scouts just west of Ashby Gap in the Blue Ridge on November 16th, Mosby sent two ranger companies under Captain Adolphus “Dolly” Richards to find and destroy the Scouts and their leader, Captain Richard Blazer. On November 18th, near Kabletown, West Virginia, about eight miles north of Berryville, Richards and his rangers trapped Blazer’s troopers, charged, and killed, captured, and scattered the Federals. Accounts vary, but about twenty Scouts were killed and another twenty captured, including Captain Blazer. The Scouts never fought Mosby again.

With the Valley relatively secure, but infuriated by Mosby’s raids, Sheridan unleashed his cavalry to wipe out the rangers east of the Blue Ridge. Mosby was promoted to colonel dating from December 7th. Action in the Valley declined, although there was a sharp encounter between rangers under Lt. John Russell and Federal cavalry on December 16th.

About four miles into the Valley west of Ashby’s Gap, Russell’s men attacked approximately 100 riders of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Charging with a yell, then firing their Colt revolvers, Russell and the Rangers scattered most of the Federals. Around thirty Federal troopers were killed or wounded, others captured. Called the Vineyard Fight, this action prevented the 14th Pennsylvania from reinforcing Sheridan’s punitive cavalry campaign across the Blue Ridge.

Although the war in the Valley was almost over, the soldiers did not know it. Mosby was seriously wounded in December, but there were still small skirmishes during the winter and spring. One occurred on March 30th, 1865, when five rangers trapped two Federals at the Daniel Bonham farm about three miles west of Berryville. Federal Lieutenant Eugene Ferris, 30th Massachusetts Infantry, refused to surrender and escaped by wounding four of the rangers. For his bravery under fire, Ferris was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Ten days later, April 9th, Confederate commanding General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia. Mosby greatly respected Lee but had no desire to surrender. He responded to one Federal query about surrender that he, “does not care a damn about the surrender of Lee, and he is determined to fight as long as he has a man left.”

On April 20th, in Millwood, Virginia, about seven miles south of Berryville, a Federal delegation under Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock tried to get Mosby and around twenty rangers to surrender at the Clarke House & Tavern. Mosby had agreed to a truce two days before, but not surrender.

During the negotiations, a ranger named Hern burst into the room and yelled to Mosby that Federal cavalry had set a trap and were hidden in the woods. Mosby rose slowly, put his hand on his revolver and said, “if the truce no longer protects us, we are at your mercy, but we shall protect ourselves.” A ranger witness later said, “had Mosby given the word, not one Yankee there would’ve lived.” Instead, Mosby and his men rode away from the Shenandoah Valley without pursuit from the Federals.

The next day, April 21st, 1865, Colonel John Singleton Mosby disbanded his ranger battalion, but never officially surrendered.