Last updated: July 12, 2023

Article

Design History of National Cemeteries

Overview

What does a National Park Service national cemetery look like? The design of each national cemetery includes character-defining features that convey both its protected atmosphere and significance as a historic landscape. Many of these features reflect the original design intent, which was generally similiar across each of the national cemeteries.

NPS /Andersonville National Historic Site

A Solemn Landscape

In the late 1800s, visitors to a national cemetery arrived by horse-drawn carriage or on foot from nearby railroad stations and steamboat piers. Located on the edge of towns or adjacent to rural battle sites, the isolated cemeteries were enclosed by masonry walls and planted with trees, shrubs, and flower beds among the uniform white marble grave markers. To the visitor, this was a notably restrained landscape compared to the meandering paths, ornate headstones, mausoleums, and sculpture of the typical Victorian picturesque burial grounds. For the nation rebuilding after the Civil War, however, the “deceptively simple” design created a solemn landscape to honor what Brevet Major Edmund E. Whitman called “the heroic sacrifice to teach to succeeding generations. . . lessons of undying patriotism.”

The War Department had done only limited long-term planning on cemeteries before the passage of the National Cemeteries Act in 1867, which also specified the construction of permanent lodges for the cemetery superintendents, masonry walls, and marble headstones. Over the next 20 years, the US Army oversaw land acquisition, the cemetery design, reinterment of the dead from shallow battlefield burials or hospital cemeteries, road and building construction, planting of trees and plants, and the acquisition and installation of permanent headstones. It was a remarkable undertaking by the US Army, which was committed to ensuring that the remains of an estimated 300,000 Union dead were buried with dignity and perpetual honor in a national cemetery.

While the War Department developed designs for permanent features, it erected temporary wooden structures through the early 1870s to support daily operations in the cemetery. These included picket fences and wood-framed entrance arches bearing the cemetery's name, “cabins” for the superintendent to occupy, and decay-prone headstones. This first generation of construction was gradually replaced by permanent features starting in the early 1870s and continuing through the 1880s.

Establishing a Common Design for National Cemeteries

Permanent features made of brick or stone became more common with the standardization of national cemetery design. Almost all the national cemeteries contained a lodge that served as a residence and office for the superintendent, as well as a few utilitarian buildings, a perimeter wall with both formal and service entries, and a centrally located flagpole.

Over the years, cast-metal signs with the number of dead (known and unknown), Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, rules of behavior, and lines from the popular poem “Bivouac of the Dead” were installed at each cemetery. Covered octagonal or rectangular rostrums were built for speakers at Decoration Day ceremonies, later known as Memorial Day, celebrated at the end of May since 1868. Memorials and landscape features of various sizes, materials, and forms, including inverted cannons, pyramids of cannon balls, obelisks, and statues were dedicated in honor of the dead. By 1920, approximately 125 memorials had been erected within the 80 national cemeteries that were established by that time.

NPS / Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

In April 1869, Brevet Major Whitman, the Army’s Superintendent of National Cemeteries, offered four “principles which should govern the selection of national cemetery sites” that would reinforce the potential for them to become historic attractions as well as shrines. These principles included localities of historical interest, convenient access, placement on the great thoroughfares of the nation, and places with favorable conditions for ornamentation.

The rows of standardized white marble headstones are a striking features of national cemetery landscapes. In 1873, the Secretary of War designated a cambered or slightly-arched marble rectangular headstone set upright for identified remains, with the individual’s name and military unit inscribed on the front side. Burials of unidentified remains were marked by a low marble block. The Army created these uniform designs at the same time it was standardizing the design of military buildings, barracks, and quarters for all its posts. The office of the U.S. Quartermaster General, under the supervision of Montgomery C. Meigs, prepared standardized plans for the cemetery superintendent's lodge. Designed in an elegant French Second Empire style with a mansard roof, the small lodges were a prominent element at the main entrance of more than 50 cemeteries.

Burial Patterns

The pattern of burials in many cemeteries followed a geometric plan suitable for level ground, despite often-undulating topography. The view of the regular rows of headstones recalled the layout of the tents in many Army camps and caused an immediate evocation as a “bivouac of the dead.” Geometric layouts featured square, rectangular, circular, and orthogonal patterns in sections defined by roads and footpaths. In some examples, graves were arranged in concentric circles around the central flagstaff mound. Although most national cemeteries averaged ten acres or smaller, they were still able to evoke the precision and patterns associated with the military in their layout.

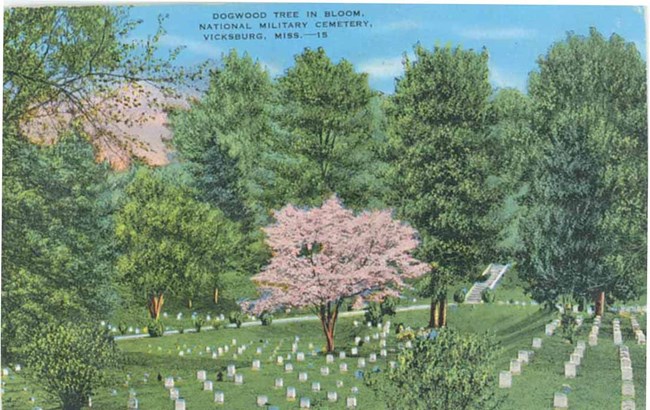

NPS / Vicksburg National Military Park

Planting Design

At the end of the Civil War, when Congress appropriated funding for the establishment and maintenance of national cemeteries, a portion of the amount was to be spent for planting and cultivating trees and shrubs. As early as 1870, civil engineer and U.S. Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army Montgomery Meigs contacted the noted landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. for advice on tree selection, placement, and care. Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, had designed Central Park in New York City in 1858, and they were working on the landscape plan for Prospect Park in Brooklyn following the war. During the Civil War, Olmsted had firsthand experience with wounded and dying soldiers as the executive secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a private organization that was the precursor to the Red Cross.

Olmsted recommended that the cemetery designs should “remain deceptively simple” and the “main object should be to establish permanent dignity and tranquility . . . a sacred grove, sacredness and protection being expressed in the enclosing wall and in the perfect tranquility of the trees within.”

Within a few years, when funds became available for landscape improvements, Meigs issued his “Instructions Relative to the Cultivation and Care of Trees in the National Cemeteries.” He recommended the planting of “cherries and pears, walnuts and hickory-nut trees” for their “well-proportioned and graceful sizes and shapes.” Meigs’ instructions also called for “climbers about the lodge” and “ornamental shrubbery.” Visual evidence confirms that many national cemeteries were densely planted and achieved Olmsted’s “sacred grove” concept.

Continuing Development and Use

Throughout the remainder of the 1800s and up to World War I, roadways approaching and within the national cemeteries were improved, and rostrums and service buildings were constructed on the cemeteries' grounds. The national cemeteries had come to have a distinct landscape identity, composed of character-defining features.

Between the two World Wars, the Army established seven new national cemeteries, some at existing facilities and others in new locations, to serve large populations of veterans. In 1973, most of the national cemeteries were transferred from the Army to the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs). To date, there are more than 170 national cemeteries across the United States. The 14 national cemeteries managed by the National Park Service were transferred by Congress to expand the portfolio of historic parks under the protection of the young agency. Since 1966, the National Park Service has been designated the lead federal preservation agency.

NPS

Past and Present

Today, the National Park Service manages the national cemeteries as designed historic landscapes, a type of cultural landscape recognized by National Park Service. While the condition of some of their features has changed or deteriorated over time, the national cemetery landscapes retain much of their integrity, meaning that enough physical features exist for the historic associations to be recognizable. The design of national cemeteries reflects the continuing belief that national cemeteries are hallowed grounds where veterans’ sacrifices can be honored.

This article is an adaptation of “Designing the First National Cemeteries”, an article by Sara Amy Leach for the National Park Service Civil War Era National Cemeteries Discover Our Share Heritage Travel Itinerary.