Last updated: February 4, 2025

Article

National Cemetery Lodges

NPS / Anthony DeYoung

Overview

Following the Civil War, the federal government began a massive effort to recover and identify remains and consolidate Union burials. The US Army Quartermaster’s Department, led by Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs, initiated a construction program for a system of national cemeteries that generally followed a set of standard plans and specifications. These plans would guide the construction and layout of enclosing walls, gates, internal drives, hedges, flagstaffs, cisterns, tool sheds, headstones, rostrums, and lodges.

As the national cemeteries protected the graves of fallen soldiers, adoption of these features also served to promote an overall sense of order, dignity, and authority. The superintendent's lodges were an integral part of this system.

A Practical and Symbolic Structure

In February 1868, Congress passed the “Act to establish and protect National Cemeteries,” which ordered (among other things) that each national cemetery contain a “porter’s lodge” at the principal entrance, in which a superintendent would reside to guard and protect the cemetery and give information to visitors.[1]

The architecture in national cemeteries was informed by both functional and symbolic considerations. National cemeteries were a tangible expression of the reestablishment of federal authority after the Civil War, and this message was reinforced by the style of the superintendent’s lodges.

For example, one of the most distinguishing features of the standard lodge design (used between 1870 and 1881) was the mansard roof, a key element in the Second Empire style. Widely used in court houses, post offices, and other government buildings in the United States following the Civil War, the use of mansard roof on national cemetery lodges associated them with other places of federal power. The mansard roof construction was also a practical choice, stretching the army housing allowance by providing nearly a full-height upper story.

At Home in the National Cemetery

National cemetery lodges were part of the cemetery design and operation, and they were also a home while the superintendent served in that position.

Initially, the Act required that the superintendents be former enlisted soldiers disabled in service. This was modified in 1872 to include honorably discharged veteran commissioned officers or enlisted men of the volunteer or regular army who may have been disabled in the line of duty.

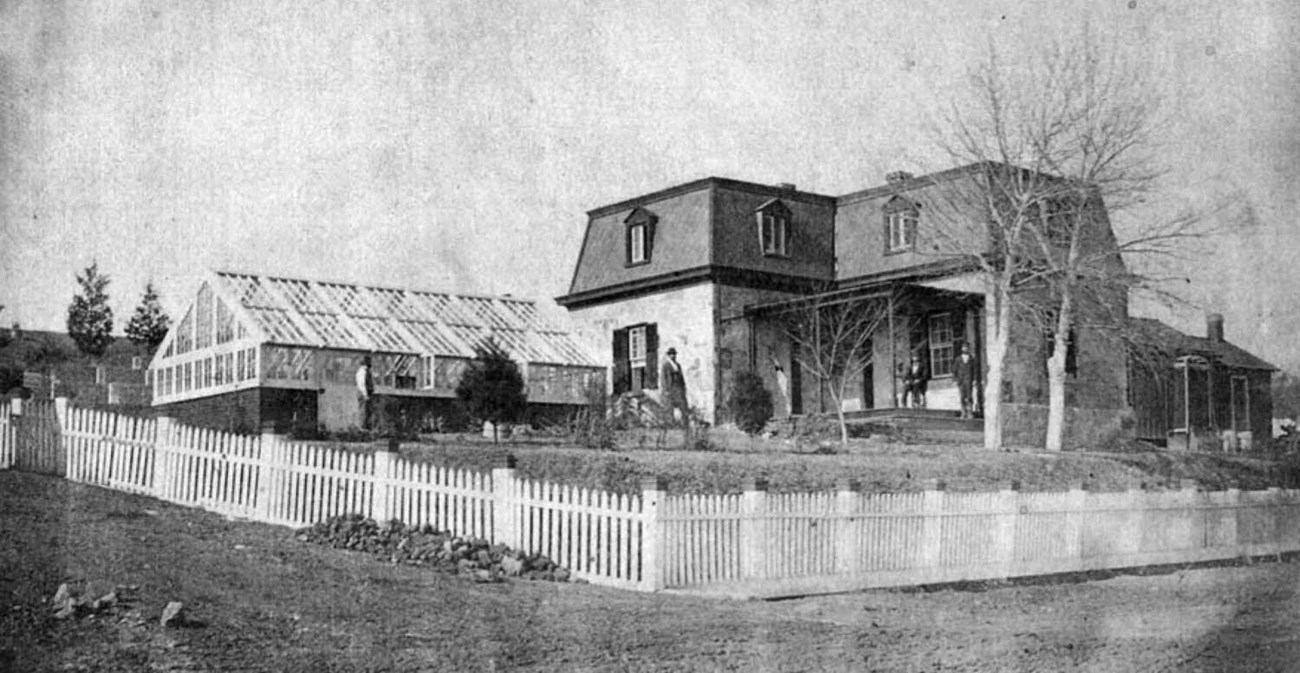

The lodge area frequently included outbuildings like a privy and kitchen, particularly for the earliest lodges that sometimes proved to be inadequate in size for the family. Sometimes, a fence screened domestic activities from view of the visiting public, and a shed or toolhouse stored the tools and equipment that were used to care for the cemetery grounds.

In 1905, Quartermaster General C. F. Humphrey reported that “these cemeteries are kept in excellent condition.” Early national cemetery superintendents personally did much of the manual labor that was required to maintain the grounds, sometimes with the assistance of hired laborers. As superintendents aged, the reliance on hired workers increased. The practice of appointing Civil War veterans was suspended in 1910.

NPS / Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Archives

Standard Design Plans

Efforts to standardize building design in the federal government began before the development of the national cemetery system. The Office of the Quartermaster General published plans for a variety of standard military buildings, intended to simplify construction planning and achieve a more uniform architectural image, but these did not appear to result in construction. Then, by the 1850s, the volume of government construction had expanded to a degree where standardization offered more efficiency, and various agencies looked to standard approaches to national construction efforts. After the Civil War, as congressional appropriations supported more military expansion and standardization, the army began to construct buildings to standard design.The development of superintendent’s lodges for the national cemeteries was an early and successful example of standardization. After an initial period of temporary lodge building in the late 1860s, the Quartermaster’s Department developed a succession of standard plans that would guide lodge construction throughout the country until about 1905. Although the cemetery lodge designs were widely adopted, there was also some resistance to a national standard for army building design. Even Meigs argued, in reference to barracks, “the question attempted to be solved is too large for any single solution… It will be found impossible in practice to apply one plan to all places, climates, seasons, and appropriations.”[2]

The attempt at a single national plan for lodges was generally abandoned in the 1900s, when the army began building loges following a variety of typical suburban house forms and styles, aligned with their local contexts and regional styles.

Photographs of National Cemeteries in the United States and Mexico [1873–1912], Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, NARA Record Group 92

Periods of Design

The Quartermaster General’s Office distributed standard plans for the first temporary frame lodges in 1867 and 1868. The early two-room lodges provided a residence for the first superintendents and a separate space to receive visitors to the national cemetery. A plan for a three-room lodge soon followed, which allowed more living space for families. Despite the distribution of standard plans, there was variability among the frame lodges. The Quartermaster’s Department built about fifty wood-frame lodges between 1867 and 1870. For a time, two- and three-room lodges were constructed simultaneously at different cemeteries, but only the three-room plan was used by 1869.In 1868, Maj. and Bvt. Brig. Gen. Alexander J. Perry wrote to Edward Clark in favor of modifying the two-room lodge design, stating that “Soldiers with families will make the steadiest Superintendents, it is thought best to allow something with a view to that.”[3] Inspection reports from this time suggest that it was increasingly common for families to occupy the cemetery lodges, often with many children. Lodges designed and constructed by the late 1880s were larger, built to more comfortably accommodate families.

NPS / Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania NHP Archives (in Fredericksburg National Cemetery Cultural Landscapes Inventory)

The temporary lodges were soon followed by a standard one-story masonry lodge plan in 1868 and 1869. The next plan was a three room, one-and-one-half story L-plan lodge with a mansard roof, created by architect Edward Clark. This design evolved through several versions for two years, until Thomas Chiffelle drew the Quartermaster Department’s definitive version of the plan in August 1871. This model was used with minimal regional adaptation in more than 50 cemeteries for the next decade.

Over time, as the standard lodges first constructed in the 1800s became stylistically and functionally outdated, they were modified, added to, or replaced. Notably, these replacements and updates did not emerge from a single design source, but followed the specific historical, regional, and operational contexts of each cemetery. Together, the national cemetery lodges built between 1865 and 1960 illustrate this progression from standard construction to stylistic diversification, revealing changing ideals about residential architecture in a memorial landscape.Today, more than 70 superintendent’s lodges stand in national cemeteries, constructed across nearly a century. Administrative changes that began in the 1930s have placed the cemeteries and their lodges in the care of different federal agencies. The 14 national cemeteries maintained by the NPS contain 11 lodges.

NPS / B. Baracz

NPS National Cemetery Lodges

Lodges by Location

This table lists the known temporary and permanent buildings built by the Quartermaster's Department for use as superintendent's lodges in the national cemeteries now maintained by the National Park Service.This table was modified from Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) documentation, completed in 2014. The information was originally compiled from correspondence, reports, and maintenance ledgers held at the National Archives, the quartermaster general’s annual reports, cemetery inspectors’ published reports, and War Department published contract lists.

For more details:

| NPS Unit | State | Cemetery Name | Date | Existing? | Style | Primary Materials | Estimated Construction Cost | Floors | Notes or Changes | Documentation | Builder | Plan your Visit |

|---|