Last updated: August 31, 2024

Article

New Study Shows How to Estimate Aircraft Noise from the Ground Up

Aircraft noise is pervasive in modern life but particularly disruptive in remote areas like national parks. These researchers focused on what people actually hear to help parks protect their quiet places.

Image credit: NPS / Tucker Chenoweth

Have you ever had to pause a conversation while a plane flew low overhead? Airplanes and helicopters may be among humanity’s noisiest creations. For the most part, national parks are places to escape the racket they make. They’re where we expect to hear soothing natural sounds that lower our stress and improve our health. Or parks may be where we hope to spot wild animals, who are often scared or harmed by noise. For others, parks may be outdoor classrooms, sacred sites, or places to celebrate or contemplate historical events—all subject to noise disruption. But even in the most remote areas of U.S. national parks, noise from jets and sightseeing air tours can intrude. A recent study published in the Journal of Environmental Management helps parks zero in on effective aircraft noise remedies by linking flight tracks with sound levels on the ground.

Lead study author Davyd Halyn Betchkal’s passion for protecting natural sounds has its roots in childhood camping trips with his dad in Wisconsin. “I think we went camping over 100 times together,” said Betchkal. “In the mornings we’d still be in the sleeping bags and he would often be telling me which birds we could be hearing. Twenty different species of warblers or something like this. It was incredible.” Today, Betchkal is a biologist and acoustician with the National Park Service’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division.

Seeking the Listener’s Perspective

“Though we think of [land and air] as [distinct] domains, they're really linked together by noise, which radiates from the airspace into the landscape of these parks,” said Betchkal. But most efforts to understand aircraft noise on the ground center around models of how sound travels from the aircraft. While helpful, these aircraft-centered models can only predict—not measure—what listeners on the ground will hear. And they're only modestly tailored to a park’s unique acoustic environment.

How close can an aircraft be without disturbing the wilderness character of a place? How close can it be before a small group of people can no longer hear each other speak?

Betchkal and his coauthors wanted to use on-the-ground audio recordings of actual aircraft to offer parks a listener-centered, park-specific way of understanding aircraft noise. They also sought to define the distances at which the noise exceeds "functional effect thresholds." These are thresholds at which meaningful changes in the resource set in. For example, how close can an aircraft be without disturbing the wilderness character of a place? How close can it be before a small group of people can no longer hear each other speak at normal volumes?

Tracking Aircraft and Their Noise

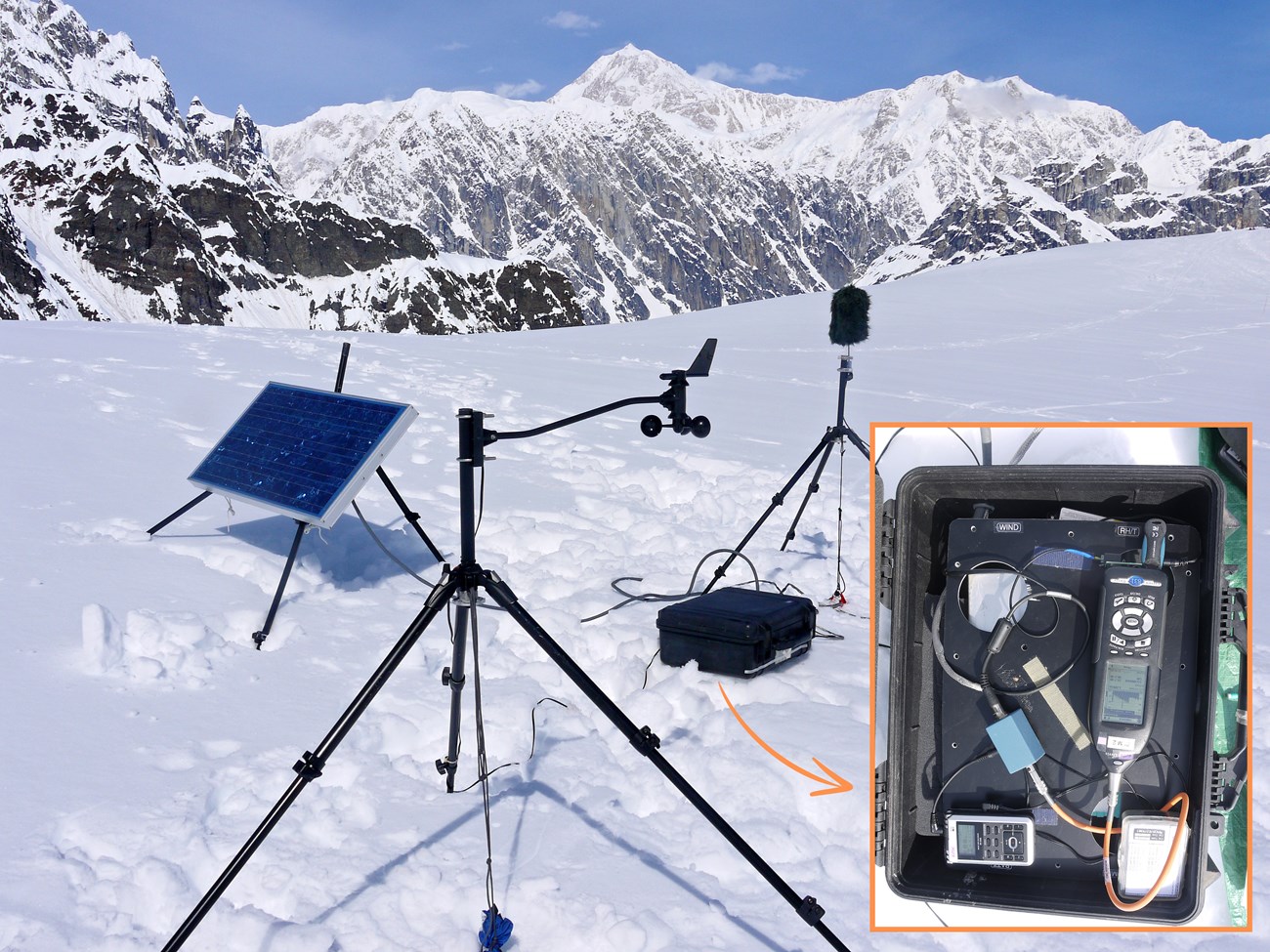

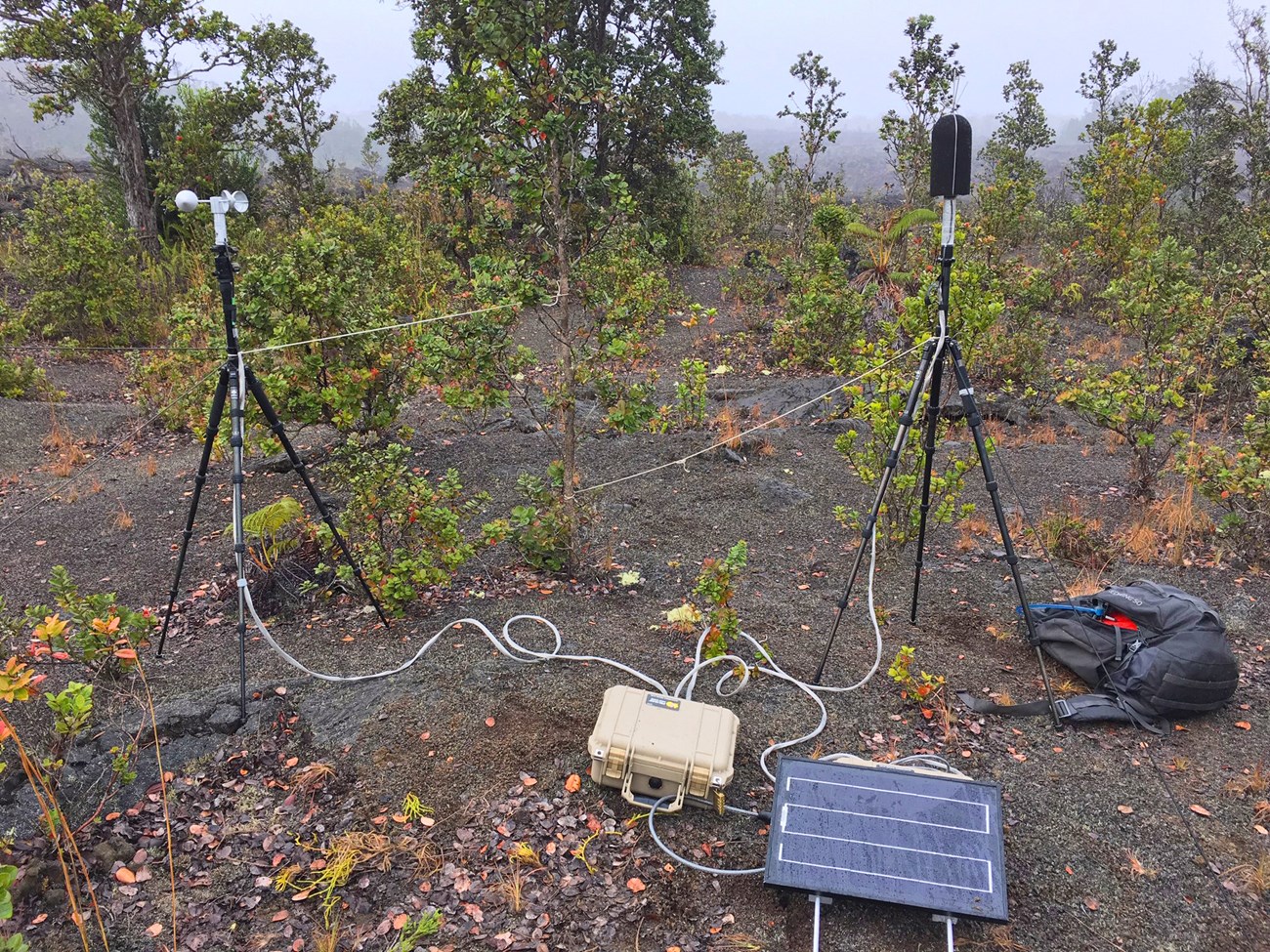

To start out, Betchkal and coauthors collected flight tracks and audio recordings from Denali National Park and Preserve and Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park. These two parks could hardly be more different. Denali, in Alaska’s subarctic region, is where Betchkal is stationed. He knows it well—which is handy for being able to gut-check study findings. Hawaiʻi Volcanoes is in the tropics, on an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Both parks struggle to balance air tour traffic with the need to protect natural and cultural resources and values, wilderness character, and the visitor experience. Because they are so different, the two parks help make the study broadly applicable.

Image credit: NPS / Catherine Sullivan

In most places, aircraft avoid collisions by broadcasting their position, speed, and identity to each other twice every second via special radio frequencies. But you don’t need to be airborne to catch the twice-per-second broadcasts. As long as they have expansive views of the sky, researchers can use specialized data loggers to receive and record the broadcasts from the ground. Betchkal and his colleagues collected flight tracks over Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park with a data logger at the summit of the Kīlauea Volcano, more than 4,000 feet above sea level. At Denali, they collected tracks recorded aboard aircraft via satellite navigation systems.

Because they are so different, the two parks help make the study broadly applicable.

The audio recordings were collected through microphones placed at long-term acoustic monitoring sites in each park. The site in Denali was atop Ruth Glacier, a destination for skiers, climbers, and visitors enjoying the scenery. The microphone in Hawai’i Volcanoes sat on the tree-covered Pu‘uhuluhulu cinder cone, a common day-hike destination. “I was really fortunate to be able to visit both locations just by chance,” recalled Betchkal. “Both locations…they're very quiet.”

Image credit: NPS / Davyd Halyn Betchkal

Image credit: NPS / Ashley Pipkin

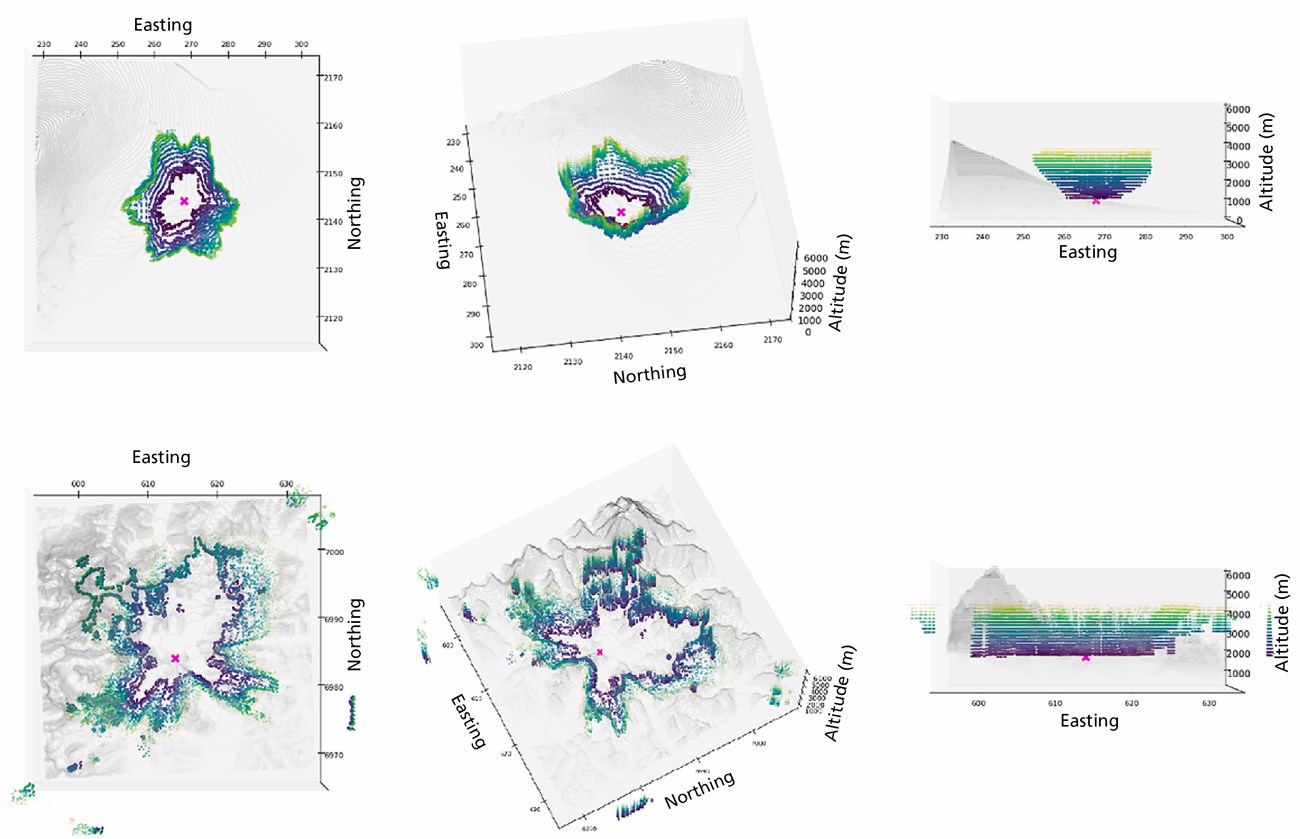

Crafting 3D Bubbles

Next, the researchers needed a way to combine their data and make sense of it. They used an existing model of how sound travels to develop a new, open-source, interactive software collection—or toolkit—called “NPS-ActiveSpace” for the task. The toolkit matches up and aligns flight tracks with audio recordings. Then it gives users a way to review flight maps and graphs of sound shapes—or spectrograms—side-by-side. Users adjust sliders below the spectrograms to indicate when flight noise is audible—when it’s at least four decibels above the natural ambient sounds in the recordings.

The toolkit connects these audible points with their measured noise levels. It uses this information in synthesis with the model of sound’s movement through space to predict two-dimensional areas of audibility around a listener. Finally, it extrapolates these measurements into three-dimensional bubbles—the observers’ “active spaces.” These spaces represent the area around a listener where, if an aircraft passed through, the listener would hear it.

Image credit: Betchkal et al., Journal of Environmental Management, 2023

“The basic result of this toolkit is a geospatial object,” explained Betchkal. “[It’s] not a number, it's a form.” For parks, that form—the 3D active space map—could be a valuable new tool. “It would give people a starting place to decide what [transportation] mitigations are going to be effective,” said Betchkal. “That saves a lot of time and a lot of failure, right?” Parks could also employ the toolkit after things like intentional route changes to track how successful those mitigations were.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

In testing their toolkit in Denali and Hawai’i Volcanoes, the researchers found that active spaces usually stretched out six miles or more around listeners. Within five miles, aircraft noise could be loud enough to disturb the wilderness character of a place. But those aren’t one-size-fits-all numbers. In Denali, for example, aircraft one and a half miles away could produce enough noise to disrupt a ranger talk. In Hawaiʻi Volcanoes, an aircraft could be a little less than one mile away before disrupting a ranger talk.

In Denali, aircraft one and a half miles away could produce enough noise to disrupt a ranger talk.

The authors aren’t sure what explains the differences. Possible reasons could include things like different atmospheric conditions (frequently clear versus cloudy), land cover (snow and ice versus tree ferns and lava rock), or aircraft type (helicopter or airplane).

Image credit: NPS

A Tailor-Made Way to Preserve Quiet Places

For their own tailored results, other parks can try the toolkit for themselves. “Right now, the tool should work in almost any environment in the National Park System,” Betchkal said. Exceptions could be very small or very urban sites. “One of the things that's really neat about being in quiet places is that you have an extensive experience of how far you can hear,” reflected Betchkal. “That's part of the feeling of grandeur” that visitors relish. The study authors hope their work will help parks keep that feeling alive.

About the author

Jessica Weinberg McClosky is assistant editor for Park Science magazine and a science communications specialist with the San Francisco Bay Area Inventory & Monitoring Network. She’s often working on either a new story map or a new issue of the San Francisco Bay Area Nature & Science Monthly Newsletter/Blog. Outside of work, Jessica enjoys nature photography and exploring new hiking trails with her family. Photo courtesy of David McClosky.