Last updated: July 30, 2020

Article

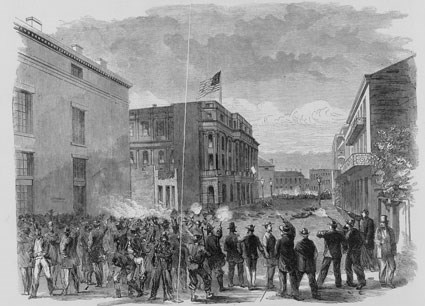

“An Absolute Massacre” – The New Orleans Slaughter of July 30, 1866

Library of Congress

The Confederate military and government collapsed in the Spring and Summer of 1865, effectively ending the Civil War with the United States preserved and slavery destroyed. But the violence was far from over. White resistance to Black citizenship during Reconstruction often turned violent – as it did in New Orleans on July 30, 1866.

During the war, President Abraham Lincoln had hoped that Louisiana, with a strong US military presence in Louisiana would serve as the model for readmitting states back to the United States. In 1864, the state ratified a new constitution that abolished slavery, but did not grant Black Louisianans the right to vote – something that President Lincoln began to consider as the war ended the next year. In his last speech, delivered on April 11, 1865, Lincoln openly expressed his desire to enfranchise select freed people and emphasized that “…voters in the heretofore slave-state of Louisiana have sworn allegiance to the Union… held elections, organized a State government, adopted a free-state constitution, giving the benefit of public schools equally to black and white, and empowering the Legislature to confer the elective franchise upon the colored man. Their Legislature has already voted to ratify the constitutional (Thirteenth) amendment recently passed by Congress, abolishing slavery throughout the nation.”1 In the crowd was John Wilkes Booth. Incensed at the thought of Black citizenship and voting, Booth assassinated President Lincoln a few days later. The violence did not stop at Ford’s Theatre.

Tennessee State Library and Archives

Within a year of Lincoln’s death, many Southern states – with former Confederates in power and backed by President Andrew Johnson, began to enact Black Codes to stifle Black political life. Tensions rose throughout the South. The first three days of May 1866 were marked with racial violence in Memphis, Tennessee when local police officers, supported by a white mob, clashed with recently discharged African American troops and in turn attacked the Black population of the city, ultimately killing 46 men, women, and children and burning 89 homes, as well as twelve Black churches.2

A little over a week following the Memphis Massacre, tensions continued to rise in New Orleans as the city’s former Mayor, and Confederate sympathizer, John T. Monroe entered the office he had been expelled from just four years prior. Monroe’s return to power embodied the ideals which Radical Republicans had long despised, and thus decided that action needed to be taken. This effort came in the form of reconvening the 1864 Constitutional Convention, with the goal of extending suffrage toward freedmen, eliminating Black Codes, and pursuing the disenfranchisement of ex-Confederates. Louisiana Supreme Court Judge R.K. Howell was to preside over the reconvened convention and declared the date of gathering to be July 30.3 Mayor Monroe declared the meeting an “unlawful assemblage,” and reached out to General Absalom Baird for Federal support in arresting the convention delegates. Baird, however, maintained that the purpose of his command was “the maintenance of perfect order and the suppression of violence.”

Gilder Lehrman Institute

Friction between the Radical Republicans and Conservative Democrats only heightened as convention delegates held a political rally in the city on July 27, and New Orleans Sheriff Harry T. Hays, a former Confederate General, deputized a posse of white officers, many of whom were ex-Confederates, with the purpose of disrupting the coming gathering. The reconvened convention met as planned at 12:00pm on July 30 at the New Orleans Mechanics Institute, with 25 delegates who filed into the building. A growing crowd of opposition waited outside, while approximately 200 unarmed freedmen, mostly veterans, approached the Institute in parade form to display their support. As the Black assembly neared their destination, several bystanders harassed and assaulted them, which ignited several isolated scuffles.

The situation quickly escalated as Sheriff Hays and his recently deputized police force arrived on the scene and began to fire into the crowd, forcing many of the freedmen to seek shelter in the Mechanics Institute, while others were wantonly massacred in the street. General Baird, whose troops had not become involved in the affair, wired to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that afternoon, “Immediately after this riot assumed a serious character, the police, aided by the citizens, became the assailants, and from the evidence I am forced to believe, exercised great brutality in making their arrests. Finally, they attacked the Convention hall and a protracted struggle ensued. The people inside the hall gave up some who surrendered, and were attacked afterward and brutally treated.” The swelling mob fired into the Institute with the intent to kill, and they infiltrated the meeting hall several times during the altercation to pull the inhabitants outside. Many of those who tried to surrender were struck down or shot. When reporting his findings to Ulysses S. Grant at the War Department, General Phil Sheridan noted that the peaceful delegates and supporters were attacked “with fire-arms, clubs, and knives, in a manner so unnecessary and atrocious as to compel me to say that it was murder… It was no riot. It was an absolute massacre by the police, which was not excelled in murderous cruelty by that of Fort Pillow. It was a murder which the Mayor and police of the city perpetrated without the shadow of a necessity.”4

Library of Congress

In a matter of approximately two hours, 34 African American supporters were killed, while the wounded numbered 119. Three of the delegates who had assembled in the Mechanics Institute were killed, while 17 were wounded, and approximately 200 others arrested. When the streets around the Mechanics Institute fell quiet, General Baird ordered martial law, which remained in effect into early August. On August 1, the Cleveland Daily Leader published sentiments that were shared by many other papers across the North: “Remember that this work was done by the constituted authorities of the city of New Orleans, rebels in record and in heart, but placed in power over loyal men by the policy of a renegade President. Remember that these scenes are but a prelude of what is to be… if Mr. Johnson’s policy shall be carried out.”5

Paired with news of the tragedy that occurred in Memphis months before, the New Orleans massacre contributed to major changes in Reconstruction policy. The 1866 elections saw to it that a Radical Republican majority ruled in both the House of Representatives and Senate, and ultimately contributed to the passing of the 14th and 15th Amendments. It could even be said that the violence which transpired on July 30, 1866, in a twist of irony, gave rise to several policies that would be enacted in following years, including Federal military presence in the South, temporary disenfranchisement of former Confederates, and for a population of more than four million freed people - the right to vote.

1 Lincoln, Abraham, and Scott Yenor. “Document 5: Last Public Address.” Reconstruction: Core Documents, Ashbrook Center, Ashland University, 2018, pp. 13–17.

2 O'Donovan, Susan, and Beverly Bond. “‘A History They Can Use’: The Memphis Massacre and Reconstruction's Public History Terrain.” The Journal of the Civil War Era, 10 Jan. 2018, www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2016/08/history-can-use-memphis-massacre-reconstructions-public-history-terrain/.

3Reynolds, Donald E. “The New Orleans Riot of 1866, Reconsidered.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 5, no. 1, 1964, pp. 5–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4230742. Accessed 30 July 2020.

4 The New-Orleans Riot. Its Official History. New York Tribune, 1866.

5 The Louisiana Convention. Cleveland Daily Leader, 1 August, 1866, p. 1.

by Park Ranger Rich Condon, Reconstruction Era National Historical Park