Last updated: November 2, 2021

Article

Nunamiut Caribou Skin Clothing and Tents

All rights reserved, Bailey Archive, Denver Museum of Nature & Science

Caribou Skin Clothing

Inland mountain Eskimos experience one of the world’s most extreme winter climates—temperatures of 55 degrees below zero or colder, often with gale force winds and blinding snow. Despite these daunting conditions, Eskimo people carry on with their daily life of hunting, fishing, gathering firewood, traveling, and camping. The key to their success and survival—above all else—is warm, effective, brilliantly designed and expertly made clothing.

The Eskimo people make their warmest clothing from caribou hide—a material that evolved over millions of years in the Arctic environment, providing caribou with unequaled insulation against penetrating cold and gales. Caribou hair is hollow, so it traps insulating air not only between the hairs but also inside them. Clothing made from this material is extraordinarily warm, lightweight, water repellent and durable.

An Eskimo hunter dressed in traditional clothing was completely wrapped in caribou skins. His parka —a hooded jacket invented by Eskimos—was made of caribou skin and worn with the fur inside. For deep cold and storms, a second parka could be worn over the first, with the fur side out. A wolf or wolverine fur ruff around the hood created a little pool of warmth that protected the wearer’s exposed face. Unlike other furs, wolverine also easily sheds the frost that collects from a wearer’s breath.

Caribou skin pants (kuliksak) were worn with the fur facing inside or outside. The socks (aliqsik) were always worn with the fur to the inside. Mittens (atqatik) were preferred over gloves because fingers are less susceptible to frostbite when cocooned in the warm pocket of air within a mitten. To stop frigid drafts, people sometimes wore caribou fur wristlets and tied a belt (tavsi) around the parka waist.

Anchorage Museum of History and Art, Ward W. Wells Collection, WWS-5122B

Caribou skin boots (kamik) are durable, extraordinarily warm, and nearly as lightweight and supple as the most comfortable slippers. No modern materials can match the combination of warmth and light weight of caribou skin boots.

Traditional Eskimo clothing is an achievement of the women, who are highly skilled designers and fabricators. Nunamiut women are expert at sewing, often critically inspecting each other’s work for the tightness and evenness of the stitching. Clothing is individually fitted to each wearer. It is also designed to look beautiful, with light and dark colored fur stitched together in elegantly attractive patterns.

A traditional sewing bag (ikpiagruk)—a pouch made from caribou leg skins—contained needles of carved caribou bone, walrus ivory, or caribou antler. The thimbles were made either from caribou skin, sheep leg bones, or caribou antler. Women made their own thread either from a single strand or multiple braided strands of sinew—a natural fiber from tendons in the caribou’s leg or back. Sinew thread is extremely strong and swells when wet, tightly filling the needle holes so the clothing is water resistant.

Anchorage Museum of History and Art, Ward W. Wells Collection, WWS-5122-9

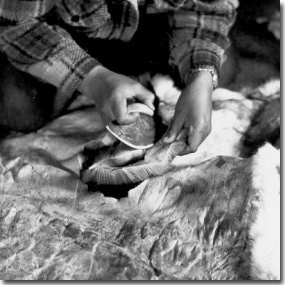

To make an item of clothing, a Nunamiut woman first dries the hide and then laboriously scrapes the leathery side to make it supple. Bull, cow, and calf hides have different qualities which suit them for specific purposes. For example, the thin, flexible caribou calf skins are ideal for parkas; mid-weight cow skins are best for mittens, pants, and socks; and winter boots are made from the lovely, durable leg and back skins of bull caribou. Hides from particular seasons also have differing qualities. Highly resilient boot soles, for instance, are made from the back skin of a large bull caribou taken in the fall, when the hide is thick and strong.

Caribou skin boots, socks, and mittens—meticulously crafted by women in the village—are still regularly worn by Nunamiut people and are regarded as superior to any commercially made substitute. While modern materials have replaced animal hide for many other items of clothing, the functional design elements still persist. For example, Eskimo people routinely add their own wolf or wolverine fur ruffs to manufactured parkas, as no better material has been found to shed snow and frost and to protect the wearer.

The parka—an Eskimo invention—is used in cold climates thoughout the world. Perhaps the strongest testament to the ingenuity and effectiveness of traditional Eskimo clothing is seen in the iconic bright red parkas with fur ruffs, worn by Antarctic researchers working in the coldest places on earth.

USGS photo by E. Leffingwell

Caribou Skin Tents

For thousands of years, ancestral Nunamiut Eskimos lived a nomadic life centered around intercepting the migrations of caribou. These animals were the key to human existence in the Brooks Range, providing not only food and clothing, but also shelter.

The long winter months brought powerful gales, protracted snowstorms, and temperatures as low as fifty-five degrees below zero. To survive in these extreme conditions, Eskimo people invented a special kind of dwelling that brilliantly met these requirements—the itchalik, or caribou skin tent.

More than just a shelter, the itchalik was a family home for Nunamiut people—the place where women sewed and children played, where people ate their meals together, where stories were told through the long arctic nights, and where knowledge was passed from one generation to the next. Even today, not far from the frame house village of Anaktuvuk Pass, there is a tent village where people go to rest, play cards, and socialize.

Helge Ingstad photo

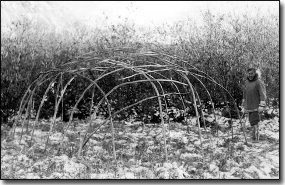

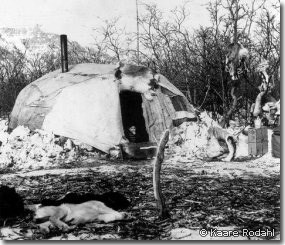

The traditional itchalik was a dome-shaped tent, constructed with a willow pole frame and sheathed in caribou skins—materials that were readily available in the Brooks Range. The caribou hides and poles were lightweight and compact, so they could be loaded onto a sled or carried by pack dogs. The itchalik could be set up quickly, providing a snug home for as many as ten people. It was weather tight, draft proof and strong enough to withstand the powerful arctic gales.

A caribou skin tent could be erected by one person, but usually a husband and wife worked together to put up their itchalik. First they found a suitable spot, close to tall willow thickets and sheltered from wind. Next they leveled an oval-shaped area about 15 feet across, clearing out snow, rocks, and vegetation. Around the edges of this oval, they set up about 20 willow poles—each about 12 feet long—with the pointed ends thrust into the ground. Once this was done, they bent opposing pairs of poles towards the center, tying them together with rawhide lashing, forming a strong, elongated dome-shaped framework. The interior space was 12 to 15 feet across, with walls four to five feet high, and rounded across the top.

Helge Ingstad photo

Good poles were valuable, so people carried them from camp to camp rather than finding new ones. The poles had been chosen carefully—straight, young willows with the fewest branches were best because they were strong and supple. They were stripped of bark, smoothed, and tapered. Poles cut in the summertime were bent around stakes on the ground to give them the right curvature. In the winter, a green pole was tied to an existing pole on the erected tent until it dried into the necessary shape.

Over this frame, the builders laid caribou hides which the women had sewn together in several panels, with the fur side out. Caribou hide with the fur left on is an extraordinary insulator because air is trapped both inside the hollow hairs and between them. Next, another layer of hides with the hair completely removed was placed over the first. These outer skins were sewn together with the same waterproof stitch used on summer boots. For natural lighting, the women sewed a translucent window made from bear intestine or seal gut into the sheathing near the door. Finally the door opening was covered by a large, heavy grizzly bear hide that generously overlapped at the edges to seal against cold and wind.

© Kaare Rodahl

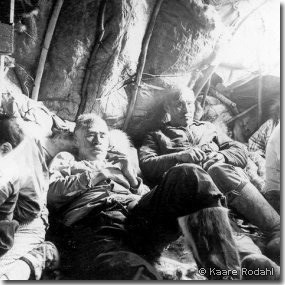

Inside the tent, women pushed thick moss tightly against the bottom edge to seal out drafts. They gathered fresh willow branches and laid them down to make a soft and fragrant floor. The sleeping area had three layers of skins: first, a floor covering made from unscraped bull caribou hides; next individual mattresses, each made from a young fall bull caribou hide; and finally soft, carefully tanned summer calf or cow skins for warm blankets. In the daytime, people rolled their blankets and mattresses up against the walls to use as back rests.

A lamp that burned seal oil or caribou fat provided heat and light—both essential during the long darkness and cold of the arctic winter. For cooking, a fire was built outside the tent and the food brought inside to eat. Rocks heated in the fire could also be taken inside for additional heat.

© Kaare Rodahl

In summer, the thickly furred caribou hide sheathing was stored and only the lighter, rainproof outer layer was used. During the warm months, people camped on the open, breezy tundra away from the willow thickets, which often swarmed with mosquitoes.

For countless generations, the traditional itchalik provided a secure and comfortable house for Nunamiut people on the move, but this began to change when modern materials became available. After they acquired wood-burning stoves, they sewed a sheet metal collar into the sheathing, which held the stove pipe and kept it from burning the hides. Eventually, people obtained gas-burning Coleman stoves; kerosene or gasoline lanterns replaced the old lamps that burned animal oils; and canvas displaced the waterproof outer layer of caribou hide sheathing. Still later, dome tents gave way to canvas wall tents, although these were sometimes lined with caribou skins for added warmth; and even today, people sleep on caribou hide mattresses in remote hunting and fishing camps.

NPS photo by Aaron Wilson

After the Nunamiut people settled permanently in the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, they lived in sod houses rather than caribou hide tents, and these in turn have been replaced by frame houses.

But reminders of an older time are still scattered across the land. Around the bottom edges of their itchalik homes, ancestral Nunamiut people laid chunks of sod, heavy rocks, or banked-up snow to hold the caribou sheathing fast against winter gales and frigid temperatures. Today, stone tent rings—some nearly 5,000 years old—can be seen in many places within Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve.

They are eloquent reminders that modern visitors to the Brooks Range walk in the footsteps of people who have made these arctic mountains a homeland for generations far beyond memory.

Tags

- gates of the arctic national park & preserve

- alaska

- alaska native

- alaska native history

- gates of the arctic national park and preserve

- anaktuvuk pass

- brooks range

- indigenous heritage

- native american heritage month

- caribou

- clothing

- arctic

- arctic culture

- subsistence

- traditional knowledge

- native stories

- culture