Last updated: July 20, 2023

Article

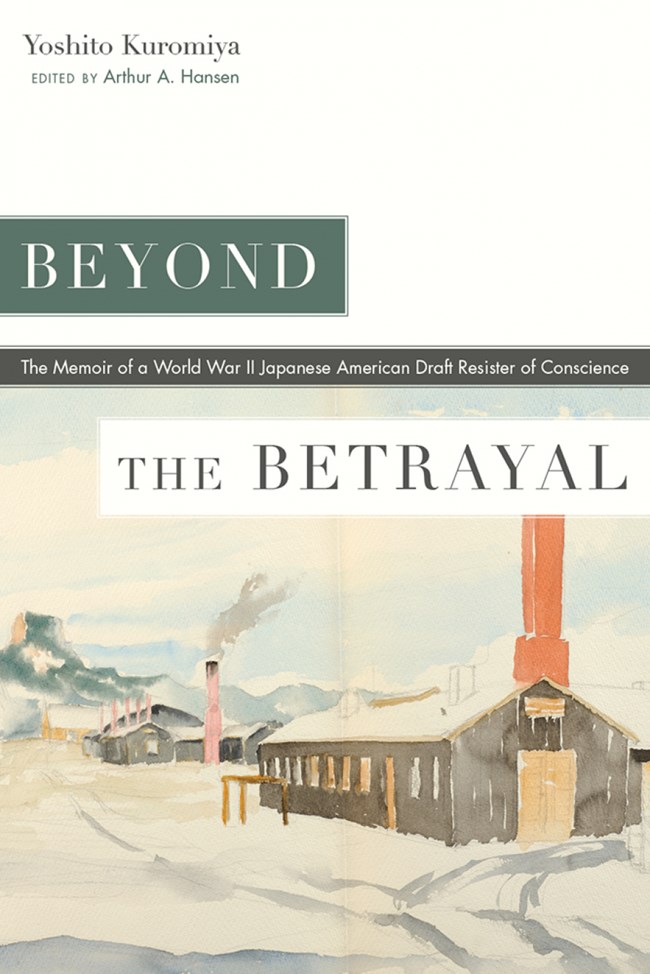

Podcast 128: Sharing the Memoir of a Japanese Draft Resister of Conscience during WWII

Why This Memoir Matters

Image courtesy of Gail Kuromiya

Gail Kuromiya: I'm Gail Kuromiya. I'm the third-oldest daughter of Yosh Kuromiya, who is the author of the book that we'll be discussing.

Art Hansen: And I'm Art Hansen, and I'm the editor of the book that we'll be discussing. I'm a retired professor in History and Asian American Studies at California State University at Fullerton.

Catherine Cooper: Wonderful. Thank you so much for joining me today. Could you talk about why it was so important to have Mr. Kuromiya's memoir, Beyond the Betrayal, published and made available to the greater public?

Gail Kuromiya: Well, if you look in the appendix of the book, you'll see that dad made a lot of appearances at conferences, universities, high schools, and whatnot, sharing his history of being a draft resister during World War II. He really wanted to get the story out to people who are interested, in particular, Japanese Americans and the younger generation. And he was actually hoping that that generation would spread the news. He felt the Japanese American community itself needed to clean its own house first and to acknowledge what happened during the war because it wasn't often shared from generation to generation. Thankfully, that's changing now, but he wanted to acknowledge what happened and learn from it and understand our own responsibilities for what happened.

Art Hansen: And from my perspective, I think Yosh Kuromiya's memoir is exceedingly important because although there were 300 plus draft resisters from the War Relocation Authority concentration camps during World War II, this is the only book-length memoir. There have been articles written, including ones by Yosh himself, but this is the only book length one. And most of the resisters have passed away. So, this was something that was exceedingly important. It was important to me too, because since 1972 when I started studying the Japanese American World War II experience, I have focused my attention on resistance activities by the Japanese Americans themselves. Not people who did things for the Japanese Americans, ministerial people and the like, but actually the Japanese Americans themselves. They had been depicted as being passive and not taking control of the situation and not defending their civil rights and their human dignity. In fact, I have found out that they did. And so, I wanted to showcase those kinds of stories. I think this is a very important story that is emblematic of this whole idea of victim self-representation of the wartime experience.

Sharing Stories Beyond Immediate Family and Friends

Image courtesy of Gail Kuromiya

Art Hansen: In my case, to give it some context, I met Yosh Kuromiya in 1995 at a conference that was held in Powell, Wyoming, and focused upon the topic of remembering Heart Mountain. And it was a big conference and everything. And I met him standing in line waiting for some lunch together. And I was immediately struck by what a remarkable person he was. And we just really hit it off and we had some very good common ground. And then years later when Yosh wrote his first draft of his memoir, he picked three people to read it and to provide some commentary on it, and I was one of the three. And I told him that I thought he should consider getting it published by a university press. And I mentioned two presses. One, the University of Washington Press. And the other, the University Press of Colorado. And the reason was because both of those presses dealt with a hybrid audience. Not just academics, but also a general audience as well.

And I thought this was a story that needed to get beyond academia and out to the larger public. Yosh Kuromiya was able to tell a very powerful one. And then I didn't hear much about it again until years later when I was contacted by Lawson Inada, who has written the poetic forward and the poetic afterward to the book as it's published by the University Press of Colorado. And he said, "Art, I have been working with the Kuromiya daughters on a family history that Yosh has produced. And I would like maybe to have you help in some way." And I think he was suggesting that I might write an introduction or something for this family book. And so, I got a copy of the family book and it was very good. And as I read it and everything, I said, "This book needs to be out in public, and it needs to be something that a lot of people can read. No matter if they live in the United States or wherever they live, they need to read this book."

Challenges of Editing a Memoir

Image courtesy of Gail Kuromiya

And when I read it, I could see why Eric was positive about the book, but at the same time, he had reservations. And he had 14 different points that he raised about factual mistakes that Yosh had inadvertently made. And so I felt that one of the things I had to do was to provide a firewall to these errors that he had made. In my endnotes, I was able to hitchhike off of Eric Muller's critique that he did for the University of Washington Press and plug in his comments and his objections to what Yosh had said. So that was one of the big challenges.

And the second big challenge was that Yosh Kuromiya was very infatuated with a book that came out by Robert Stinnett, and the title of the book was Day of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor. And this was a book that was very controversial. In a sense, it said that Roosevelt knew when other people didn't that Pearl Harbor was going to be attacked. And he let it be open to attack because this provided a back door for the United States getting into war against the Nazis in Germany and against the fascists in Italy. That was the premise of the book. Yosh believed that this was the case. And so, when editing it, I had to go through many, many book reviews of that book by diplomatic historians and get a sense of their critical opinion. And I was able to show in the two-pages long endnote that there were book reviewers, for instance, that supported what Yosh supported about this conspiracy of Roosevelt's and the dastardly act of Roosevelt. And then there were many other reviewers of it that felt that he had not proved his thesis, that he had a warm barrel, but not really a smoking gun.

The other challenge I had was that a good friend of mine and a superb historian at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Diane Fujino, who had put a lot of time into putting forth the manuscript that was submitted to the University of Washington Press. And so, I didn't want to proceed with this project unless I had Diane Fujino's blessing. And she is one of the most gracious and nicest women. And she willingly said, "Art, go ahead with it." Diane Fujino was willing to take it to a second university press, but Yosh was not. He said, "I'm old. And at this particular point, all I want to do is to get this book out. And I'll get it out as a family book." Anyway, those were the main challenges that I had as an editor. Otherwise, there wasn't much of a challenge at all. It was a great opportunity and I was working with great people.

Publishing Takes a Network

Gail Kuromiya: There's a lot of other people he didn't name that were really important to him, but primarily it was Lawson Inada, who Art mentioned, retired professor and former poet laureate from Oregon State. He's the one who connected Art with the family. Martha Nakagawa is a journalist in Los Angeles and close friend of both my dad and my stepmother. Art, of course. Without him, this book would probably be sitting on a shelf somewhere in the family version format. And of course, he acknowledged his daughters. My oldest sister, Suzi, is a retired professional graphic designer. She did the original layout for the family version, which was retained for the final version. My next oldest sister, Sharon, from New York, was dad's editor from the very beginning when he first started sending us files. And in the final version when we were working with the University Press of Colorado, Sharon was the one who tracked down all the images that we had used in the family version to verify that we had permission and copyrights and all that kind of stuff.

And although all of us are graphic designers, all of dad's four daughters, we weren't very familiar with the whole final publishing process. Design and layout are two things, but all that technical stuff is beyond us. And then my youngest sister, Miya, she's the only one of us who's still working. So, her involvement was minimal in the beginning, but she provided a lot of emotional support for all of us. And then dad acknowledged his second wife, Irene, who was not only his wife, but his personal assistant, his typist, secretary, driver, groomer, all those things. And I would add a lot of other people. My mother, Haru, was family cheerleader and supporter and all-around good sport, my husband Paul, for being so patient since this became my retirement job, essentially. And many other people.

And although all of us are graphic designers, all of dad's four daughters, we weren't very familiar with the whole final publishing process. Design and layout are two things, but all that technical stuff is beyond us. And then my youngest sister, Miya, she's the only one of us who's still working. So, her involvement was minimal in the beginning, but she provided a lot of emotional support for all of us. And then dad acknowledged his second wife, Irene, who was not only his wife, but his personal assistant, his typist, secretary, driver, groomer, all those things. And I would add a lot of other people. My mother, Haru, was family cheerleader and supporter and all-around good sport, my husband Paul, for being so patient since this became my retirement job, essentially. And many other people.

Differences in Japanese American Experiences during WWII

Image Courtesy of Library of Congress National Archives

And then they became part of the great 442nd Battalion and it is one of the most decorated units ever in American military history. And I think that's what the American public wanted to hear, the fact that no matter what you do to people, America's so important that you would never hold it for account. And I think what the Japanese American draft resisters did and what Yosh does in his book is to hold not only the United States government to account right up through the President of the United States, but also to hold into account the leadership of the Japanese American Citizens League, because they were corroborators with the US government in the incarceration of their own population. I think to have somebody like Yosh Kuromiya, they would like to look at him as being unpatriotic when in fact his whole act of draft resistance was patriotic. He believed in the Constitution of the United States, and we need to live up to that. And that's what he tried to do along with the other draft resisters of conscience is to make the United States live up to that. So draft resistance was exceedingly important.

A Family Project

Image Courtesy of Gail Kuromiya

And so, in 2010, he sent me his first chapter out of the book. And one thing I do want to mention is that once he had his manuscript where he was comfortable with it, and we had done the family version, he was adamant that nothing be changed from his original manuscript through all of the publishing process. And other than grammatical errors and things like that, Art, to his credit, maintained that. The final book that people will read are dad's words. So, from 2010 until dad died in 2018, constant phone calls with dad, conversations that I probably never would've had the opportunity to have with him because it went beyond his experiences during the war as a resister and all the stuff surrounding that before they went into the camps, afterwards, my childhood, that type of thing. And of course, not all of that is in the book because it's not a tell-all book. But it was really valuable and it got harder and harder because dad started losing his hearing, and that made it really difficult.

He didn't use the computer, so I have all his long hand-written notes. I took notes when I talked to him on the phone, which I'm kind of going through now and coming up with these little pearls of stories that I would not have known had I not been having this ongoing conversation with him. So that was the primary memory of this whole process. And even though the book itself is quite an accomplishment, I still think that the phone calls are what I will cherish the most out of this experience, because a lot of Nisei dads are not typically very talkative about their personal feelings and emotions. But I think, through this process, dad got more and more comfortable sharing that type of stuff. So that was a real positive that came out of it.

Art Hansen: In my case, I just have one story that I'd like to relate. It has to do with Yosh's widow, Irene Kuromiya. And when this edited version of the manuscript was being considered to be published by the University Press of Colorado, Irene had registered a protest. And it came to me and it hurt me a lot because I regarded and still regard Irene as a very close and dear friend of mine. She said, "Art Hansen, he was sent the manuscript by Yosh years ago, and he didn't even read it. He didn't even say anything about it," which was absolutely untrue. Not only did I read it, I wrote about a seven or eight-page critique of it, including even a copyediting section to it. And somebody reminded her of that fact. And I think she somehow rather had blanked on it.

What she was upset about more than anything is she felt that what Yosh wanted really was not a published book, but just the family edition for family and friends. That's all he wanted. And I had to, in a sense, go against that, by talking to Gail in particular, to find out at bottom what Yosh wanted. He might have said, "I want just the family edition," but he really wanted something that would get out to a much larger group so that this important story of not just himself, but the story of himself in relationship to the draft resistance movement would become public knowledge. And then almost to the end, Irene still wanted just the family book. But she came to the book event that we had at the Japanese American National Museum. And I think she was very gracious at that event. And you could tell that she was bubbling over with pride. She loved her husband so much and was so proud of his memoir and her own involvement in it. But I think all of the other stuff was washed away.

The Importance of Decisions and Responses

Gail Kuromiya: Dad wanted to present his manuscript as a personal account. He didn't want it to be an academic document. And he did want to get it out to the public. But at the same time, I think he had a mistrust of the commercial printing process. But one of the themes that he was trying to get across in the memoir, and we talked about this before he passed, was the role of the Issei, his parents’ generation who immigrated here from Japan. So, he attributes a lot of his decisions as being influenced by my grandfather and the morals and integrity he had.

But overall, I think the takeaway from the book is included in Cherstin Lyons' condensed review on the back of the hardcover version. And I believe it's a quote out of dad's text. It reads, "What is a citizen's rightful response to constitutional transgressions? What indeed is a citizen's responsibility when racially-based civil rights restrictions are imposed by an errant government?" I think that sums up the gist of it, even though Dad always told me that he didn't intend this to be a portrayal of him as a resister. Because he said even though that was a pivotal decision in his life, it wasn't his entire life. And that's why he insisted on including all of the rest of his life in the book as well.

Art Hansen: I think that the major takeaway of Yosh's book has been expressed nicely by Gail in that quote that she read. Actually, another important thing that I'd like readers of Beyond the Betrayal to take away is Yosh's entire life, not just his time in camp or in prison, et cetera, or fighting for the rights of the resisters against the JACL and others after the war. But really to see that his entire life is a tribute to not just his acts, but to the man himself and the character, the deep and abiding character of that particular person.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you both so much. This was wonderful.

Gail Kuromiya: Thank you.

Art Hansen: Thank you so much, Catherine.

But overall, I think the takeaway from the book is included in Cherstin Lyons' condensed review on the back of the hardcover version. And I believe it's a quote out of dad's text. It reads, "What is a citizen's rightful response to constitutional transgressions? What indeed is a citizen's responsibility when racially-based civil rights restrictions are imposed by an errant government?" I think that sums up the gist of it, even though Dad always told me that he didn't intend this to be a portrayal of him as a resister. Because he said even though that was a pivotal decision in his life, it wasn't his entire life. And that's why he insisted on including all of the rest of his life in the book as well.

Art Hansen: I think that the major takeaway of Yosh's book has been expressed nicely by Gail in that quote that she read. Actually, another important thing that I'd like readers of Beyond the Betrayal to take away is Yosh's entire life, not just his time in camp or in prison, et cetera, or fighting for the rights of the resisters against the JACL and others after the war. But really to see that his entire life is a tribute to not just his acts, but to the man himself and the character, the deep and abiding character of that particular person.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you both so much. This was wonderful.

Gail Kuromiya: Thank you.

Art Hansen: Thank you so much, Catherine.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.